OP-ED

Mugabe’s ‘kiss of death’ sealed Chamisa’s poll defeat

In a country still smarting from Mugabe’s ruinous four decades in power – a president who once boasted of having “degrees in violence” that seemed to be actualised in the 1980s death of thousands of opposition supporters in southern Matabeleland and the Midlands provinces – the ex-president’s backing of Nelson Chamisa was seen by a large number of Zimbabweans as an attempt to bring Mugabe back to power “through the back door”.

As Zimbabweans pondered their future this week in the aftermath of a tightly contested general election, supporters of chief opposition leader Nelson Chamisa were still stunned at how their orator-pastor had been trounced by President Emmerson Mnangagwa.

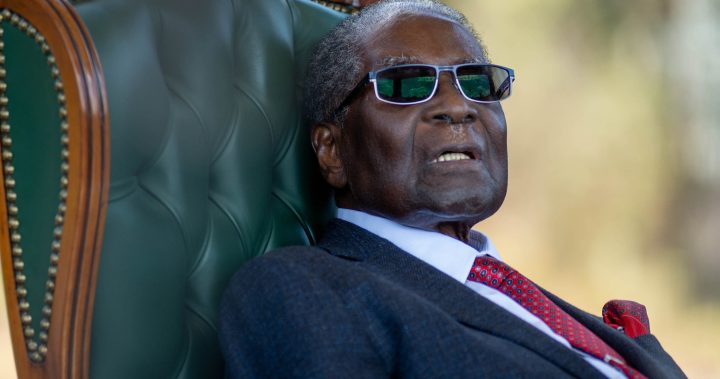

And yet several signs of Chamisa’s political loss in the polls had been foregrounded, if predictable, long before the elections, the latest harbinger of his troubles being the “kiss of death” that he received from former president Robert Mugabe, who was ousted by the military in November 2017.

Mugabe’s open support for the 40-year-old leader of the opposition Movement for Democratic Change (MDC) Alliance, intriguingly on the eve of a critical election last week, had effectively sealed Chamisa’s political fate after persistent media reports linked him to the former president, including charges that Mugabe had donated at least US$24-million in cash and cars to the opposition leader’s campaign.

In a country still smarting from Mugabe’s ruinous four decades in power – a president who once boasted of having “degrees in violence” that seemed to be actualised in the 1980s death of thousands of opposition supporters in southern Matabeleland and the Midlands provinces – the ex-president’s backing of Chamisa was seen by a large number of Zimbabweans as an attempt to bring Mugabe back to power “through the back door”, to use Mnangagwa’s telling words.

In short, Mugabe’s support had badly dented Chamisa’s brand in the eyes of some Zimbabweans, who thronged the streets of cities in November 2017 in celebration of Mugabe’s toppling by the military, which subsequently installed Mnangagwa as head of state in one of a few military coups that have rocked southern Africa after a series of military-led insurrections that have blighted Lesotho’s political landscape since 1986.

Aside from Mugabe’s eleventh-hour intervention in the 30 July general elections, a range of variables had seemed to stymie Chamisa’s chance of victory.

The first was the sheer uneven spread of voters between those in urban areas, where the MDC has the greatest support, and the rural areas, where most Zimbabweans live and where Mnangagwa’s ruling Zanu-PF party has long enjoyed strong political support for a variety of reasons, including alleged intimidation of villagers.

In the name of what the government has branded as its “Command Agriculture” that is meant to boost Zimbabwe’s self-sufficiency in food, especially of the staple maize, the government had for the past few years poured huge amounts of funds into rural and peri-urban areas to improve the livelihoods of voters there.

Often residents in the rural areas were given significant farming inputs such as fertilisers and seeds and, ahead of last week’s elections, even thousands of cattle to restart collapsed livestock farms, mostly in dry and parched Matabeleland provinces.

Mnangagwa, in power for just seven months before the 30 July plebiscite, was therefore keen to use his brief incumbency to demonstrate to rural dwellers that his government was delivering tangible “gifts” of his revolution –a revolution he said was necessary to ensure Zimbabwe catches up with the rest of the world after years of isolation caused by Mugabe’s factitious ties with the West.

Mnangagwa’s “gifts” included the opening or refurbishment of two power stations in northern Zimbabwe; the opening of some closed factories (such as the regional Pepsi headquarters for southern Africa in Harare), and a couple of manufacturing outlets, to try to woo voters and show that Mnangagwa’s new mantra of “Zimbabwe is open for business” was indeed bearing real fruit, however modest.

In contrast, Chamisa appeared to hobble his campaign by promising too much too soon, including claiming that he would end Zimbabwe’s endemic cash shortages within weeks of taking over power. But Zimbabwe’s huge domestic and international debt – one Zimbabwean economist, Eddie Cross, estimated the country’s total debt at US$30-billion this week – and the government’s ever-ballooning budget deficit in the face of non-existent exports to earn much-needed foreign currency, simply militate against such a solution being cobbled up within weeks.

Significantly, Chamisa was caught in a cross-hairs dispute with Donald Trump’s administration after Chamisa proclaimed that the Americans had promised him billions of dollars for Zimbabwe’s reconstruction if he won. In the event, the US publicly denied his claim and asked him to apologise – a development that did not endear the opposition leader to Trump’s maverick government and maybe to Zimbabweans, who have become inured to the empty claims of the Mugabe years.

No sooner had the dust settled on this controversy when Chamisa, seeking to shore up his image among regional African nations, said he had helped Rwandan President Paul Kagame with advice to set up Rwanda’s now famed and successful Information and Communications Technologies infrastructure in the East African country. Kagame quickly took to Twitter to flatly deny ever meeting nor knowing Chamisa, deriding him for telling lies.

While all of this was happening, some observers noted Mnangagwa’s big push to meet regional business leaders and investors from across the world and the political leaders of the SADC to spread his “Zimbabwe is Open for Business” slogan.

Crucially, Mnangagwa visited China – a long-time ally of Zimbabwe – where he won immediately implementable multibillion-dollar deals which resulted in the relaunch of some stalled power stations in Zimbabwe and help with investments in several cash-starved sectors.

The British government, criticised by some Zimbabweans for appearing to favour a Mnangagwa presidency since the November 2017 coup, and a private bank, Standard Chartered, released US$100-million to prop up private businesses in Zimbabwe.

As the election edged closer, Mnangagwa interrupted his election campaign to fly to South Africa to confer with the BRICS leaders, including Chinese President Xi Jinping; Russian leader Vladimir Putin, whose companies have long eyed investing in Zimbabwe’s mineral-rich Dyke, and South African President Cyril Ramaphosa, who quickly congratulated Mnangagwa for his poll win.

Chamisa’s election thrust – that he would win the election whatever happened and that anyone who suggested victory for Mnangagwa was merely peddling “fiction”? – did galvanise his youthful and unemployed troops. But as Kofi Annan, leading a delegation of The Elders to the Zimbabwe poll, did note a week ahead of the elections after meeting most key political leaders there, including Chamisa, there was a marked difference between campaigning and inciting followers to break the law.

As Zimbabweans this week counted the cost of at least seven dead in riots that erupted after the elections, as MDC supporters sought to hurry the Zimbabwe Electoral Commission to release the election results ahead of the constitutionally mandated four days did show, there was impatience on the ground to get “this thing over quickly”.

But some within Chamisa’s MDC have criticised both his dalliance with Mugabe and his strident stance against what even the Western-backed Zimbabwe Election Support Network – a grouping of civic bodies which have spearheaded voter education in Zimbabwe and observed polling across the nation – has judged as an election result which approximates its own pre-poll surveys, dealing Chamisa a heavy blow in his planned challenge of the election results.

One journalist colleague who has also reported on Zimbabwean events for years put it succintly.

“All in Zimbabwe and outside now await the evidence of rigging of the elections which Chamisa says he has got and is taking to the Zimbabwean courts. He needs to provide compelling evidence; otherwise many people will see his actions as bordering on ‘politricks’. The long-suffering people of Zimbabwe want to go forward.”

The journalist colleague, who preferred not to be named, added:

“So many factors stood against Chamisa’s win. Just to imagine that the army would take over power from Mugabe and then hand it over to Chamisa for Mugabe to exercise power through his proxies is beyond me. It’s a serious misreading, if not miscalculation, of Zimbabwe’s complex political landscape.” DM

Francis Mdlongwa is an international journalist and editor who covered Africa, including Zimbabwe, for the global multiple-platform news provider Reuters for more than a decade. He writes here in his private capacity.

Become an Insider

Become an Insider