OP-ED

Bhisho court judgment makes infrastructure part of the right to basic education

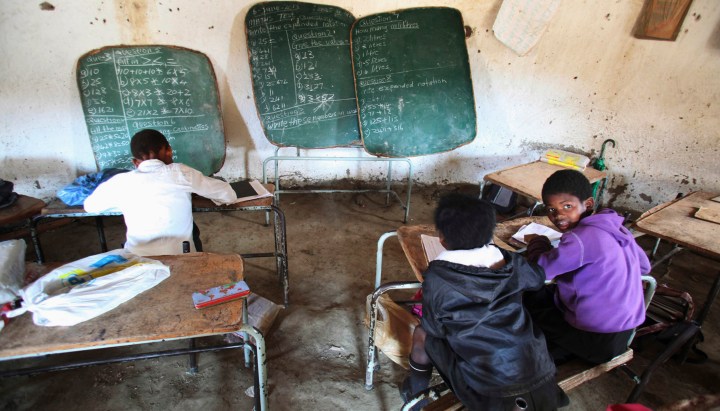

A Bhisho High Court ruling gives effect to government’s obligations to provide public school infrastructure. At last, we have an effective road map for improving school infrastructure in South Africa’s under-resourced schools.

The judgment handed down in the Bhisho High Court by Acting Judge Nomawabo Msizi earlier this month in the case of Equal Education v Minister of Basic Education (the “Equal Education” case) declared several sections of the Regulations Relating to Minimum Norms and Standards for Public School infrastructure to be inconsistent with the Constitution and the Schools Act and therefore unlawful and invalid.

It is hoped that the regulations can now provide an effective road map for improving school infrastructure in South Africa’s under-resourced schools.

The judgment also has the potential for significant jurisprudential impact that can be used by civil society advocates leveraging the transformative potential of the unqualified right to basic education in section 29(1)(a) of the Constitution.

This is because the judgment further develops the evolving jurisprudence in respect of the right to basic education by its explicit acknowledgment of school infrastructure as an important component of the right. It, hopefully, once and for all, puts paid to yet another iteration of government’s persistent attempt to circumvent its duty in respect of the immediate realisation principle when it comes to the right to basic education. It requires that the constitutional principle of public service accountability imbue and underpin legislation seeking to give effect to government’s rights based obligations.

The court application was initiated by the social movement, Equal Education (EE). The Limpopo-based organisation, Basic Education For All (BEFA), represented by SECTION27 intervened as amicus curiae (“friend of the court”) in support of the application. EE challenged the constitutional validity of several sections in the regulations.

The publication of these regulations, in fact, only occurred as a direct result of a protracted legal battle between the Department of Basic Education (‘DBE”) and EE, the latter arguing that the regulations were legally mandated by section 5A of the Schools Act that requires the minister to prescribe minimum benchmarks for school infrastructure after consultation with the Minister of Finance and Council of Education Ministers.

The regulations establish minimum benchmarks in respect of provisioning for, among other things: classrooms, electricity, water, sanitation, libraries, laboratories, electronic connectivity and perimeter security. They also set incremental target dates for meeting specified goals.

The main challenge to the regulations was in respect of sub-regulation 4(5)(a) which makes compliance with the minimum benchmarks “subject to the resources and co-operation of other government agencies”. The problem with this provision is that it effectively creates a legal loophole for government to indefinitely avoid its obligations to provide safe and adequate school infrastructure. This loophole can ultimately serve to render the regulations ineffective.

Previous cases initiated by civil society have produced judgments that have significantly contributed to the normative development of the right to basic education by incrementally defining a basket of entitlements that make up the right to basic education. These cases further entrenched the immediate realisation principle.

The Constitutional Court case of Juma Musjid Primary School v Ahmed Asruff Essay NO (Juma Musjid) distinguished the unqualified right to basic education from the qualified socio-economic rights. These include the rights to further education, health care, food, water and social security. In respect of these qualified socio-economic rights, a court merely has to determine whether the measures adopted by government to progressively realise the right over time are reasonable. This has been termed the “standard of reasonableness review”. By contrast, in Juma Musjid, the court held that the right to basic education is immediately realisable. Juma Musjid also laid the foundation for identifying the different components that make up the content of the right. The effect of this is that once a court identifies a particular component of the right, government is obliged to immediately provide that component of the right.

Following this judgment, several progressive civil society organisations, emboldened by the promise of the Juma Musjid judgment and seeking to improve the quality of education in the poorest schools initiated a series of cases for improved education provisioning.

As a result of this, several components of the right were identified by the courts. In the Supreme Court of Appeal (SCA) judgment, in the case Minister of Basic Education v Basic Education for All (BEFA), the court held that every learner is entitled to a textbook in every subject. In the case Madzodzo v Minister of Basic Education, the Eastern Cape High Court held that there is an obligation on government to provide desks and chairs to learners in schools. In the case of Tripartite Steering Committee v Minister of Basic Education, the Eastern Cape High Court held that the right includes a direct entitlement to be provided with transport to-and-from school at the state’s expense for those learners who live a distance from school and who cannot afford the cost of transport.

Somewhat less explicitly, in a string of teaching post provisioning cases, the courts have suggested that teaching and non-teaching posts in schools are further entitlements in respect of the right to basic education. While there have also been cases dealing with school infrastructure – including the case initiated by EE for the promulgation of the regulations – until now, these cases had consistently been settled in favour of applicants without any judicial pronouncements (which create enforceable law) in respect of school infrastructure as a component of the right to basic education.

In the Equal Education case the DBE’s basic argument in respect of sub-regulation 4(5)(a) was that the provision is necessary because its efforts are hamstrung by lack of adequate resources, budget and by the other organs of state. The DBE argued that it is constrained by the principle of co-operative governance. Thus, while the minister is accountable for the provision of basic education, “she cannot be accountable for the provision of infrastructure as that is outside of her competence” and rather falls within the function of other departments such as that of Public Works or Finance as it pertains to budget.

In a somewhat discombobulated, two-pronged argument to circumvent the immediate realisation principle and impose the reasonableness review (through the back door) as a lower threshold for reviewing government’s compliance with its basic education obligations, the DBE argued that while at first glance the right to basic education is immediately realisable, the “enabling legislation” giving effect to the right – in this case, the regulations “is progressively realisable like any of the other relevant [socio-economic] rights.” Secondly, that “the applicant is introducing a new undefined standard of quality different to the one that is in the enabling legislation.”

The DBE argued further that the appropriate standard ought to be “whether reasonable measures have been put in place by the state.”

It should not go unremarked that this latter argument was made by the very same counsel in the BEFA case in respect of the obligation to provide textbooks – albeit differently phrased – wherein he argued that the obligation to provide textbooks to every learner was to hold government to ‘”an impossible standard of perfection”. This argument was dismissed by the SCA and ought therefore ought not to have been repeated by this same counsel.

The Equal Education judgment was in any event strongly dismissive of these arguments. Through a methodical outlining of the key basic education cases which are discussed above, the judgment reaffirms the standard of review in respect of the unqualified right to basic education adopted by the courts thus far. The court further dismissed the argument that the minister’s hands are tied and that she is at the mercy of other departments and organs of state. Instead the judgment asserted that this approach “simply compromises the constitutional value of accountability”, a principle that in terms of section 195(3) must underpin all national law, including the regulations.

In a key passage that succinctly sums up the reasoning of the court in finding the loophole provision, sub-regulation 4(5)(a) to be invalid, the judgment noted:

“I cannot fathom a reason why, given the nature of the right in question, and the abundant crisis, the respondent cannot develop a plan and allocate resources in accordance with her obligations. In the event that she is unable to do so, it is incumbent on her to justify that failure under section 36 or 172 (1)(a) of the Constitution. This she has not done.” DM

Faranaaz Veriava is Section27 Head of Education.

Become an Insider

Become an Insider