FLIXATION

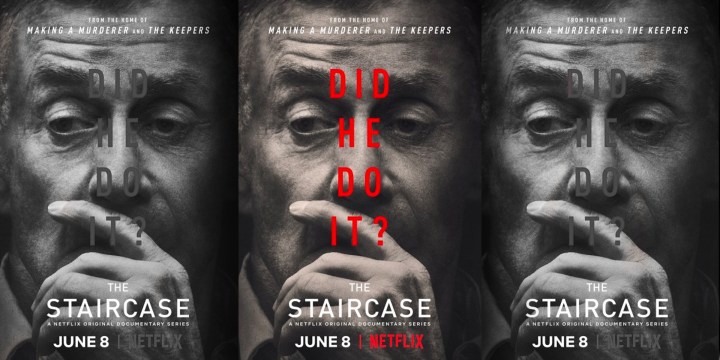

The Staircase: Who’s guilty? The accused, the jury – or the US criminal justice system?

The Staircase is a phenomenal piece of contemporary documentary making. From almost the moment an apparent crime has been committed in 2001, and for another 13 years and more to follow, the cameras are on the accused and his family as he and his right-hand-man lawyer seek justice. The only moment that seemingly was not committed to video was the crime itself, which is to be picked apart with painful scrutiny for years to come. If only there had been footage of what really transpired, one closely bonded family may have been spared years of anxiety.

This warrants a who’s who to kick off with. The main characters in this seemingly endless set piece are, chiefly, a cultured novelist and father, Michael Peterson, his sons Todd and Clayton, his adopted daughters Margaret and Martha Ratliff and his staunch brothers Bill and Jack; Michael’s measured, dogged attorney David Rudolf; Candace Zamperini, the lip-curling sister of his late wife Kathleen; Kathleen’s daughter Caitlin; a judge who we see move from middle-age to seeming near retirement; a jury that includes a matron who I sure as hell wouldn’t want to have decide my future, and a succession of witnesses, chief among them one Duane Deaver, who may or may not be a lying bastard who should be locked up.

The supposed crime: On 9 December 2001 at their plush home in Forest Hills, North Carolina, Kathleen and Michael Peterson – who writes fiction set during the Vietnam War – are in their garden near their pool, a little tipsy, when she needs to go inside for a tinkle. After some time, when she hasn’t returned, he goes inside to find her at the foot of the stairs, surrounded by blood, with blood spatter on the walls, some apparent smears, and no sign of any weapon. This is either “his story”, or the truth, and 13 episodes ploddingly, yet ever intriguingly, seek that truth. We are to see and hear much more about those blood spatters in the years to come.

Watch the official Netflix trailer:

The prosecution led by District Attorney Jim Hardin puts almost its entire case behind its claim that Peterson bludgeoned his wife to death with a “blow poke”, a hollow fire poker that you can blow through to kindle a flame. The unlikeable Candace had given a blow poke to many members of the clan. The Peterson one is missing.

Complicating matters for Michael Peterson is that, years earlier, a woman friend of his, Elizabeth Ratliffe, had died in Germany under similar circumstances – stairs, much blood, and many apparent blows to the skull. It is hinted at, but seems unlikely, that Michael and Elizabeth had had an affair. Friends who knew them at the time deny this.

Adding to his troubled case is that Michael is bisexual, and had paid-for encounters with male escorts during his marriage to Kathleen. It’s no stretch to imagine how much of an effect this knowledge can have on a jury of untrained minds whose number may or may not include the odd bigot. It stands to reason. As for Candace Zamperini, it is on the point of hearing that Michael is bisexual that she switches from avid support to a war cry for his conviction.

Aiding his case is that both his adopted daughters love him and stand by him, insisting that they have no doubt whatsoever that he could never have killed their mother (as they call her), whom he loved. Learning that their adoptive father is bisexual, and about his affairs, is not enough to change their minds. They simply accept this as an interesting aspect of the man that they hitherto had not known about. They virtually take it in their stride.

Watch: And then there’s the Owl Theory

On the other side of the bar, however, Caitlin, Kathleen’s daughter, persists in her belief in his guilt. But let’s back up a bit, because while Margaret and Martha are indeed Michael’s adopted daughters, their mother is not Kathleen – they are the daughters of Elizabeth Ratliffe, the friend who fell down the stairs in Germany. The girls’ parents and the Petersons had had an agreement that if anything were ever to happen to them, they would bring up their daughters, which happened (the father had died too), and which they did.

Behind the camera is the French team of director-producer Jean-Xavier de Lestrade, who Peterson hires at a very early stage so he will have a video record of whatever might transpire. In doing so he inadvertently gave the world a remarkable insight into how criminal justice works – or doesn’t work – in America. What transpires is that this will keep De Lestrade and his team busy, on and off, for well more than a decade.

The result is something utterly extraordinary: we’re flies on the walls of a deeply complex murder mystery, every step of the way, to the extent that you frequently marvel that the camera can seemingly go everywhere they go. Even the cops and wardens are compliant, allowing the camera into cells, prison yards, even following a man from the dock, down the stairs and through the door, beyond which we normally do not see a freshly convicted murderer. Like the moment when Henri van Breda was led to the cells. You never expect to see hide or hair of him again, at least for many years. But no, there we are: there the man sits, on a bench against the wall, hunched over, contemplating his fate after a jury has decided it; waiting to be shackled at the ankles, bundled into a van, driven to a prison. Regardless of masses of worryingly unsatisfactory evidence, despite there being a sizeable quantity of what we’d think of as benefit of the doubt, and plenty that falls short of “beyond reasonable doubt”.

The French title of The Staircase is Soupcons (“Suspicions”, rather than the small morsels that gourmands take it to mean). It is now presented as a 13-part series, but the initial package was aired some two years after the alleged crime, with a further chapter filmed later and only recently three final episodes released. The result is a 13-part Netflix package, bundled into one.

Key to getting deeply involved in this true drama is to imagine yourself in the various roles, on all sides. If you were on the jury, would you be the lone voice questioning all the others? Were there any such dissenting voices? Seemingly not, given the unanimous verdict.

If you were Michael Peterson, knowing you were innocent, would you have the willpower, stamina and mental strength to see it through to the end? If, on the other hand, you were Michael Peterson and knew you were guilty, would you be able to keep up the charade for years, facing and eyeballing family, friends and legal supporters?

If you were attorney Rudolf, just how much doubt would you have? He claims none at all, but really? Off camera, surely, he must have thought, what if…. And if you were any of the astonishingly supportive daughters, sons and brothers, how would you react if you turned out to be wrong. If he had done it.

And if you were the runt Duane Deaver, would you do the honourable thing and commit seppuku? (Nah.)

Then there is the factor of the District Attorney, Jim Hardin, who goes on, as the years progress, to become a very big fish in the local legal pond. He’s an exceptionally good prosecutor, measured and cunning in court, an interrogator whose barbs you’d battle to dodge, yet in the end his introduction of a key witness, the palpably unpleasant Deaver, early on in the original trial is the factor that turns the tide against Peterson. When time brings in a wave of new information, how must the man feel, how much does it dent his legal and personal pride? And his sidekick, Texan fashion plate-cum-assistant DA Freda Black, whose closing arguments are pinned on the “fact” that because Peterson is bisexual and liked having sex with men, he killed his wife all of a sudden one day when they were having a drink at the pool. This, inescapably, played a part in whatever was in the individual jurors’ minds while they were deliberating for those many days. Does she just shrug it off and go off to do her hair, again, and try on another new outfit?

As much as The Staircase is about the murder, the trial and the repercussions, it is also about a family holding together against almighty odds. There can be no faking of these bonds, of the staunchness of their support for him – with the one exception, the set-lipped Caitlin.

And you have to wonder: if the end result is emphatically, without a shadow of a doubt, that Michael Peterson has never killed anyone, that he loved his Kathleen and that she would have been mortified (perhaps not the best choice of word) at his persecution in the years following her death, isn’t something wrong with the US justice system, and specifically, with their jury system?

The problem with citizen jurors is that they have no legal training, they have none of the volumes of knowledge that a legal practitioner must study over many years before being qualified to practise law and then, only after some decades of experience, to be even considered for promotion to the halcyon heights, judge.

And then, that judge, with all his learning and experience, ultimately merely announces the verdict of a bunch of no-nothings. Isn’t that plain ridiculous? DM

Become an Insider

Become an Insider