David Goldblatt (1930–2018)

Giant of SA photography used his lens with precision and compassion

David Goldblatt was one of South Africa’s best known photographic chroniclers. For seven decades, he explored a series of critical explorations of South African society. He is one of our countries major artistic figures, someone who has captured time and space in images that are burnt onto the collective consciousness. And politically, Goldblatt was often a lightning rod.

Born in the West Rand mining town of Randfontein in November 1930, David Goldblatt was the son of Jewish shopkeepers who, as children, had fled anti-Semitism in Lithuania.

During his own childhood, he could not avoid regularly seeing a very South African manifestation of racism, “There was a clear view from the back of our house to the police station. Every morning one would see a group of African people in the yard of the police station… handcuffed together in rows and they would be marched through the town to the magistrate’s court at the other end of the town. And I can still remember my feelings of outrage at the injustice of this, of the indignity that these people were made to suffer.”

In other ways, growing up in Randfontein was idyllic and he recalled fond memories, some of which he had captured to film. Some early surviving prints of his school friends, taken on a simple medium format camera, possibly a Box Brownie but likely something that was easier to look through, show an awareness of the moment and of composition.

One standout is a close up of a schoolmate’s head as he sleeps on another’s lap during a school outing on a train.

David began to take photography seriously in 1948, the year the National Party came to power. His elder brother had served in the merchant navy and returned with a 35mm camera. That Contax rangefinder was one of the pioneers of the miniaturisation of cameras and had swept through photography like a veldfire. Like so many of that generation, Goldblatt took to these supremely portable cameras; they were quick to operate and discrete, almost like an extension of the eye. Looking at some of the images from that period transport us instantly to the world of a small mining town.

He wanted to be a photojournalist in the tradition of the Life magazine photographers, but marriage to Lily and his father’s illness forced him to take over the family business – a men’s outfitters in Randfontein. He was studying part-time at Wits and would credit an economics lecturer with instilling in him the intellectual rigour he would apply throughout his life.

After his father’s death, he sold the store to work full time as a professional photographer.

Paul Weinberg, photographer and long-time friend, said: “I love his early work … I see elements of spontaneity there, because he was discovering.” Goldblatt himself tended to self-deprecatingly distance himself from that early work in later life, “I am not terribly impetuous and my photographs are not great wells of spontaneity. I would be the first to admit this and that may well make them quite boring and dull to many people. Sometimes to me also…”

In 1966 and 1967 he travelled quite extensively through the country working on his essay on Afrikaners. He had a Peugeot 403, a pup tent, a sleeping bag and a small primus stove. “Mostly I camped at the side of the road and on farms, often without the tent,” Goldblatt recounted, “I only did it for about two to three weeks at a stretch, so it wasn’t too bad.” That ascetic approach has been a constant to his work; discomfort would never distract him.

Goldblatt was one of South Africa’s best known photographic chroniclers. For seven decades, he explored a series of critical explorations of South African society. He is one of our country’s major artistic figures, someone who has captured time and space in images that are burnt onto the collective consciousness. “I was concerned to put down on film some of the things that to me were indicative of the values, of the ethos, that prevailed in our society. I was not satisfied with what I did, I knew that there were much deeper levels to which I should have penetrated somehow, but I did not know how.”

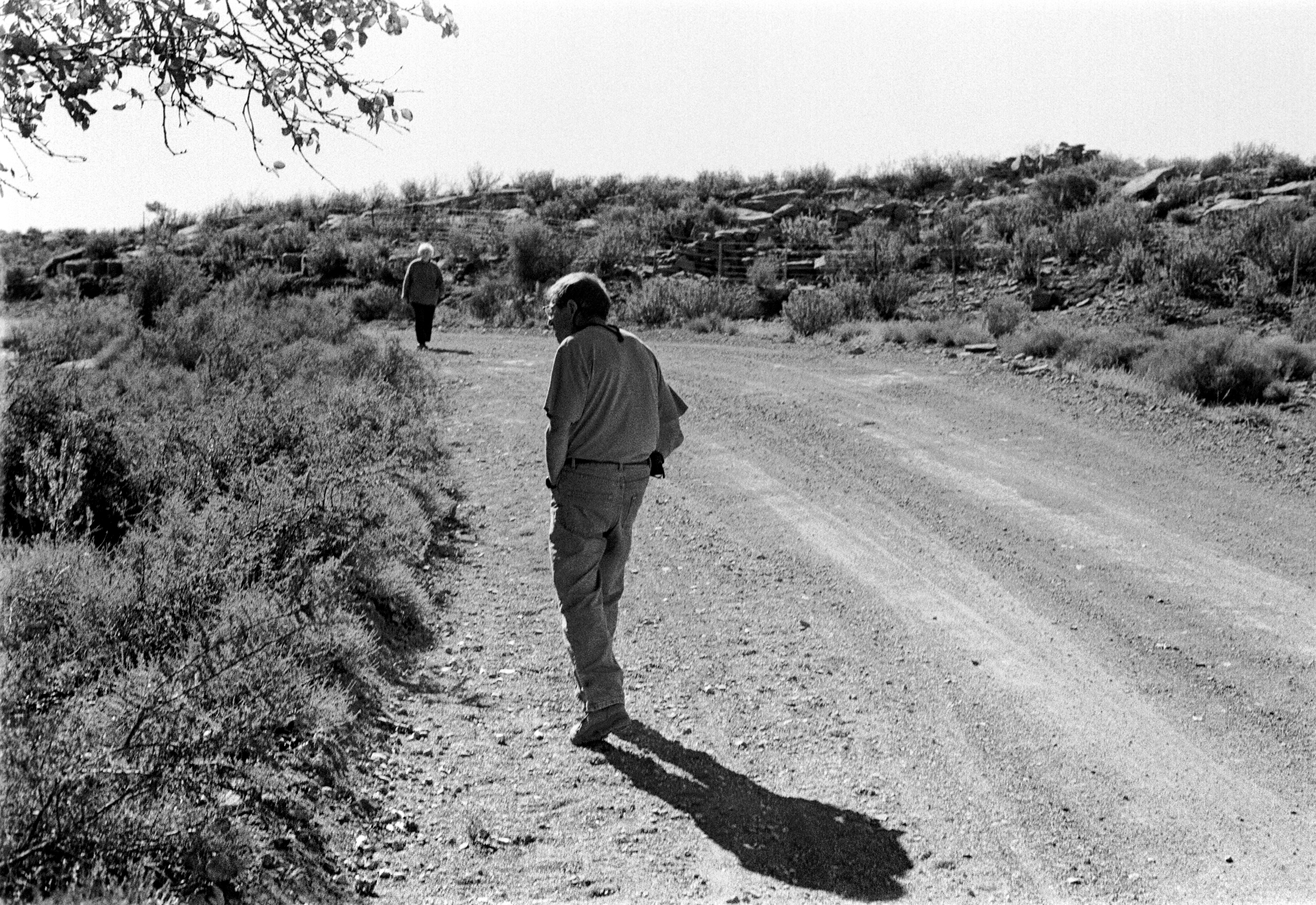

David and Lily Goldblatt, Karoo, May 31, 2004. Photo © Greg Marinovich/(@GregMarinovich)

In a society defined by racial identity and the relationship between the races, his photography would consistently follow the path of apartheid and its impact on life, infrastructure and even the very earth.

“He is what he does,” photographer Santu Mofokeng noted, “he was actually talking about apartheid, about this life, in a way nobody else was doing. There aren’t too many Goldblatts. It’s a kind of calling – what he does has meaning.”

Goldblatt soon grew disenchanted with trying to photograph in an explicatory way, “I realised roughly in about 1968 that I wasn’t really interested in talking to people outside South Africa, because the situation was too complicated and the things that I was interested in photographing were too oblique, too ingrown, too convoluted for people who were not born into the country to understand. I found when I tried to show these photographs outside South Africa it was like trying to explain jokes.”

“I was interested in the underbelly of the society, in its values and how they came to be formed and in particular, how they came to be expressed. How do we come to the values we hold and how do we express these values? These to me are the vital questions.”

His work from Soweto in the early 1970s was very much true to his evolving approach, “I knew I had to pursue my photography as a means of raising my voice against what was happening; I had to pursue it in my own way. I had to get beyond the ‘Ag shame’ level of liberalism as it applied to photography. I needed to become aware of people as people, as individuals and somehow to contain that awareness in the photographs.”

Thirty years later, on a return visit to some of the people he had photographed, Goldblatt was painfully self-aware of his own shortcomings within the South African environment, and of never having learnt an African language, “if people accused my pictures of African people of lacking intimacy, I would understand where that came from.”

That observation did not slow him, he knew what he had to do, “The photographer is responsible for critically observing and if we want to preserve the values we regard as democratic and for which there was this great struggle we have to be very vigilant, and the price of liberty is vigilance… it’s incumbent upon us to observe critically. I don’t regard ‘myself as a missionary, I’m not in the business of beating a drum. The distinction is sometimes a little blurred, but for me it’s on the whole pretty clear. So, I have been over the years asked by various people if I would allow my photographs to be used for much more directly political concern, in other words for advocacy, and I have always refused.”

“It involved me in open conflict sometimes with people whom I respected very highly and with whose political views I agreed. But I differed strongly over the use they made of photographs. I knew that my engagement was there, but that it differed from a lot of other people. It certainly wasn’t comfortable sometimes to have that difference. I was sometimes quite lonely.”

Said Mofokeng, “David’s work is much more intellectual, it is not visceral. What he actually does is not in your face.”

In the late 1970s, he chose to document a white community in a very ordinary way, “How is it possible to be law abiding, normal and decent in a society and in a system that is fundamentally evil? This was my question to myself really, I could not answer it…” This led him the town of Boksburg on the East Rand. Like his Soweto work, he shot this in medium format, on the Hasselblad.

“Apartheid was the overwhelming present system within which we lived. I tried to see people within that for what they were. I was much more interested in the underbelly, in what life was like to be black. And eventually what life was like to be white. I looked at both of these things, or I attempted to.”

This was, perhaps, where one sees most clearly Goldblatt starting to find the intellectual groove that would dominate his later work. Shortly thereafter he would begin his iconic series Structures, a 15-year-long project, mostly out of a van, “I worked out that the cost of hotels and the smell of stale cigarette smoke and Ricoffy in country hotels. So, the VW camper. I used it extensively for 10 years, staying mostly in caravan parks.” By then, he was using a four by five view camera as his preferred tool.

The images from Structures are compelling and masterful, digging deep into what South Africans believe in, “We have built our structures to express ourselves in a very naked way. Our churches are, in my opinion, an amazing expression of values.” It was this that would lead to his breakthrough as a seriously considered international artist, if I can use that word. And in the meantime he started the Market Photo Workshop which saw so many young, underprivileged photographers given the chance to attain a career.

All through those years, Goldblatt did commercial and editorial photography to subsidise his real work. His relationship with Anglo American also gave him access to the mines which would lead to the 1973 book On The Mines. He was also the photo editor on Leadership magazine, which allowed him to assign talented young photographers.

In 2002 he decided to explore rural South Africa. After a few trips into the Karoo and Northern Cape, it became clear that he would be very restricted in what he could do. He began looking at “modern” transport options. Goldblatt joked about investing his children’s inheritance in a four-wheel drive camper. It would prove to be a great investment as this self-contained vehicle allowed him to explore the theme of earth in language that was precise, pure, clean.

It is an austere rendering of photography, often of landscapes and urban-scapes that do not, at first sight, seem compelling.

“Landscape is a very difficult subject for photography, largely because of scale. It does not easily reduce to a little rectangular paper. You need to become peculiarly aware of how the landscape works, or how the land works. I don’t like the term landscape because that implies already that you’ve brought a certain kind of order to it. The whole problem of photographing the land is to find a way of doing it that conveys a certain visual order but which at the same time doesn’t look like you have organised it.”

While Goldblatt did not, perhaps, impose on the land he photographed, he certainly gave us a new way of looking at it, referring to this work as photographing fokol, “I think that I persist because I detect that there is an element in that photograph that is quite important to me albeit that it is dull and lacking in obvious excitement, there is something there that I want to pursue and make manifest. I’m interested in the ordinary. I don’t wish to make it extraordinary, I don’t wish to dramatise it. I want somehow to retain its ordinariness. I want to retain the quality often found, of banality. Then there isn’t a quality of tension. There is something in that and it might be very thin, it might be very elusive.”

As he dug deeper into his sub-conscious and into the country’s psyche, he found himself choosing colour, shooting large format negatives and then having them scanned and printed to his exacting standards. This sometimes led to a muting of the vivid tendencies of colour film into something subtler. Later, he would use a digital medium format for some of his work.

While doing this, already a man in his seventies, he received the Hasselblad award and discovered that the foundation had a set of the late Ernst Cole’s images. Many of these had formed the basis for House of Bondage published in 1967 when Cole was in exile from his native South Africa, but these original printed were uncropped, closer representations of the original negatives. This led to a retrospective exhibition and book, Ernst Cole Photographer (2010).

Politically, Goldblatt was often a lightning rod. He was an anti-racist white liberal when that was almost (but not quite) a radical position, yet as black politics came to the forefront of public consciousness, he was asked to become more politically involved and to use his work as a direct voice.

He refused, not because he was opposed to the politics, to the contrary, he agreed with the politics. He did not want his work to be, or be used as, propaganda, even for caused he agreed with.

Goldblatt was nothing if not consistent. When Jacob Zuma was still president, he conferred The Order of Ikhamanga which recognises excellence in the fields of arts, culture, literature, music, journalism and sport on Goldblatt. Goldblatt responded with a terse and cutting letter, which refers to a bill passed in Parliament that he felt undermined democracy and the rule of law, he ended with this sentence, “To accept the Order of Ikhamanga from you on April 27 would be to endorse your contempt. I refuse to do that and, very sadly, I decline the honour.”

More controversially, Goldblatt decided to remove the collection he had donated to the University of Cape Town because he felt the rights and freedoms of artists were no longer protect by the university in the wake of the Rhodes Must Fall and Fees Must Fall campaigns that saw artworks destroyed and work censored by student activist groups. The collection moved to Yale University in the US.

The massive achievements of Goldblatt would suggest a driven, singular man, yet he was generous, warm and down to earth, with a keen sense of self-deprecating humour. As so many of the tributes to him would suggest, he is truly irreplaceable. DM

Sources:

David Goldblatt has died (Mail & Guardian)

Conversations with Goldblatt (Vimeo)

Become an Insider

Become an Insider