Op-Ed

David Goldblatt: The Art of Capturing a New truth

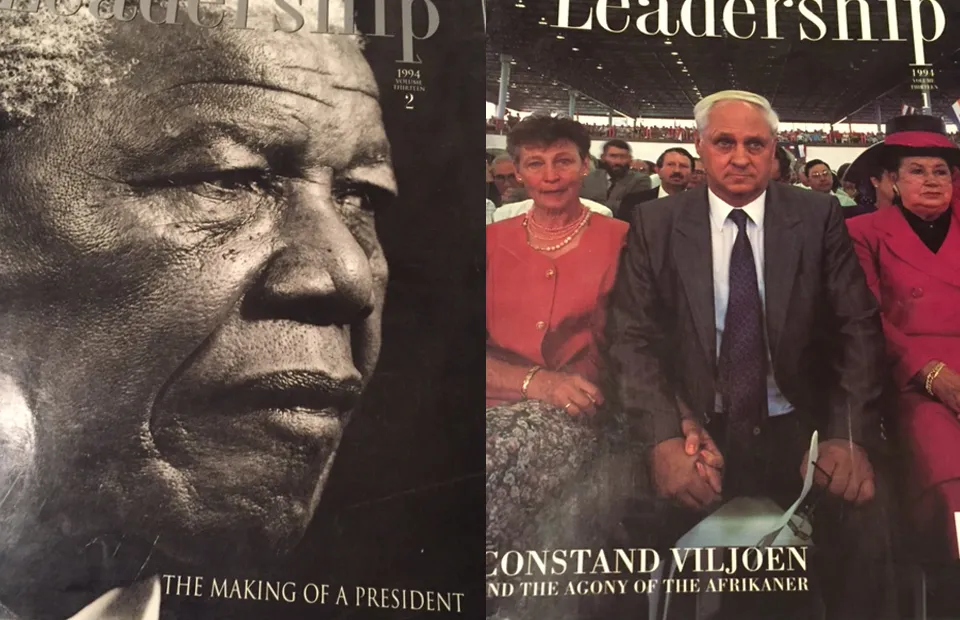

At a rally of far-right Afrikaners, Goldblatt kept his lens trained on Constand Viljoen in the front row. Viljoen clutched the hand of his wife, Ristie, grim-faced, as she wept while Terre’blanche raged. It was the moment of truth about the dissolution of the right-wing backlash.

About three months before the first democratic election, I went with David Goldblatt to a rally of far-right Afrikaners who hoped to organise resistance – armed if necessary – to the forthcoming democracy.

It was the story the international press had been waiting for. Scores of photographers and journalists were there, as was the far-right leader Eugene Terre’blanche, head of the Afrikaner Weerstands Beweging (AWB).

So too was Constand Viljoen, the former Defence Force head, whom the right-wing had anointed a year before as their reluctant saviour.

Viljoen’s talk about a peaceful route to a “Volkstaat” did not cut it that night with the openly racist and belligerent crowd. He tried to preach his message of peace against angry shouts of “nou, nou, nou” (Now, now, now).

He sat down, shaken, as Terre’blanche, the fanatical rabble-rouser, took the stage. Every camera trained on the AWB leader as he strutted and yelled his stuff. This is what the world’s press had come for, after all.

But Goldblatt kept his lens trained on Viljoen who had returned to his seat in the front row. Viljoen clutched the hand of his wife, Ristie, grim-faced, as she wept while Terre’blanche raged.

It was the moment of truth about the dissolution of the right-wing backlash. Viljoen was not prepared to back this crowd. When the AWB led the doomed foray into the Bophuthatswana homeland not long afterwards, he washed his hands of them and joined the negotiations with the ANC. The AWB strayed further to the fringes. Viljoen became a member of the new democratic Parliament.

Only Goldblatt captured that precise moment when Viljoen saw a new truth. Even in the midst of a press scrum, the veteran photographer sought out moments that were portenders.

I was fortunate enough to work with Goldblatt for several years in the mid-Nineties, the years of change and hope and violence. We both worked for Leadership magazine, then under the editorship of Peter Wilhelm, a vehicle for narrative journalism and documentary photography like few other publications.

Goldblatt was much more than a photographer. He was an artist, a journalist, historian, and seer. He had already published his famous book on the Afrikaners, which chronicled the rise of nationalism among ordinary folk, and was working on a book of apartheid architecture, The Structure of Things Then, seeking out the hidden stories that buildings tell us about social structure. Later, after apartheid, he did an equally quirky but brilliant collection, Regarding Intersections: he photographed the 122 points in the country where the full lines of latitude and longitude cross.

He never believed the cliché that a picture is worth a thousand words, although in his case it was close to truth. He was a firm believer in captions and the importance of context. In his evocative series on Fietas, in Johannesburg, before the community was removed under the Group Areas Act, he has a picture of the twin hand-carved beds in the main bedroom of the Docrat family. It told a story but not the entire one: each of the magnificent carved beds had to have six inches cut off each one to fit through the doors of the family’s new home in the “Indian” group area of Lenasia.

Or, in another example, a poignant portrait of a domestic worker with two toddler children in her employer’s home, published in a collection edited by Paul Weinberg, tells the story of an era in its caption: “Victoria Cobokana, housekeeper, in her employer’s dining room with her son Sifiso and daughter Onica, Johannesburg, June 1999. Victoria died of AIDS on 13 December, 1999, Sifiso died of AIDS on 12 January, 2000, Onica died of AIDS in May 2000.”

He treated each of his subjects with respect although he had little time for the sycophants who tend to cluster around the powerful.

Shortly before the 1994 election, Goldblatt, Wilhelm and I went to interview Nelson Mandela in his Houghton home for a cover story for Leadership. Carl Niehaus, as unctuous then as he is today, was the ANC spokesperson at the time. We had arrived at dawn for our breakfast appointment with Madiba. Goldblatt scanned the room for a suitable place to take a portrait and did not like the look of the lounge furniture. He did not want Mandela slouching in the picture, he said. He asked to see the upright kitchen chairs, and Niehaus snapped that “the president could not be photographed in a kitchen chair”.

“I haven’t come to take a picture of the furniture,” Goldblatt snapped back. Niehaus backed off and the cover photograph of Nelson Mandela, taken in profile, captures a rare moment of somberness and reflection before he assumed his historic task.

But his respect was never deferential: he once used the window of my little office in Parliament when I was political editor of SABC’s radio news to photograph the entire Constitutional Assembly just before the new Constitution was signed into law in 1996. He had carefully arranged the 400-odd delegates on the steps of the National Council of Provinces. But the negotiations were not quite over; a flurry of urgent talks were happening as the picture was being posed.

“Can that restless little group in the middle settle down please,” he boomed through a megaphone he’d hired for the occasion.

The restless little group included Cyril Ramaphosa, Roelf Meyer, FW de Klerk and Thabo Mbeki.

Two years earlier, he, Wilhelm and I had kept an 8pm appointment at Kempton Park to interview Ramaphosa and the National Party’s Roelf Meyer. The two had kept talking after negotiations had broken down under a weight of violence and massacres; 8pm dragged to 9pm, and eventually to 1am the next morning. The two men wearily obliged Goldblatt by posing in the now famous hand-clasp, half shake, half wrestle.

But the photographer whose work was exhibited in museums and galleries around the world was always more interested in those who did not make headlines – farmers, mineworkers, domestic workers. He had an endless curiosity about the country. He once told me he never went on holiday, not because he didn’t have time, but because he got bored away from work. Occasionally, he admitted, he’d unwind by taking a day off to read a novel.

He eschewed materialism; he was dismayed by the conspicuous consumption and later outright corruption that became the hallmark of the new elite.

Yet he was a man of impeccable taste. He would not drink instant coffee or eat margarine, even in the far north of rural KwaZulu-Natal, where we spent the week of the 1994 election in huts. He’d brought proper coffee, which he boiled up over a fire the old Boer way, letting the grits sink to the bottom of the pot, and olive oil for his bread.

As in every aspect of his impeccably balanced life, there was no compromise on these culinary essentials.

Born in 1930, Goldblatt leaves his wife, Lily, and three children. DM

Become an Insider

Become an Insider