SCORPIO

TRAINSPOTTER: Alexkor Meltdown – Northern Cape’s state-owned enterprise non-gift that keeps on taking

If you were looking for a blueprint on decisively how not to help the growth of an entire region – and how to help shrink a shrinking South African economy – the Northern Cape diamond industry is happy to oblige.

“The original version of this article contained the statement that Hantsi Matseke’s husband, Peter ‘Kop’ Matseke “has intimate financial ties with Gupta consigliore Salim Essa”. We retract that statement unconditionally. The statement was based on the fact that Dr Matseke was listed as a co-director of a company linked to Gupta associate Salim Essa, during the period 15 November 2010 to 1 February 2013. Except for that listing, Dr Matseke is not to our knowledge associated with Salim Essa or the Gupta family in any manner and we apologise to Dr Matseke for any harm he may have suffered as a result – Editor”.

Diamonds are another story. They are exquisitely transportable, they need no railways. But of all the precious minerals sought by man, the store-house of the diamond has been most difficult to find.

— Lawrence Green, Coast of treasure (1973)

Jesus dives

Gavin Craythorne began his walk with the Lord some 20 years ago. Tall, pony-tailed, and with a rock-like jaw that suggests unwavering determination, he is now a member in good standing of Alexander Bay’s NG Kerk congregation. (In a neat summary of the town’s economic picture, the church recently lost its brass bell to several enterprising junkies). When the organist is absent, Craythorne is called upon to DJ the backing music. The tattoo winding along his forearm means, “Everything in the fullness of God’s time.”

“Ja, I used to be quite impatient,” he explains.

Alexander Bay, a remote Northern Cape dorp hugging the Namibian border, demands from its inhabitants an excess of patience. Craythorne’s arrival in this small mining and fishing community coincided with his religious awakening. For most of his adult life, he has worked as a marine miner. This is the ass-end of the diamond business, where the objective is to scrounge from the seabed either alluvial or aeolian stones borne by river or wind into the paleo channels that criss-cross the ocean floor.

Gavin Craythorne (Photo by Richard Poplak)

The Orange River delta – the river’s last gasp before it hits the Atlantic in a churning, muddy mess – constitutes Alex Bay’s furthermost border. This is by far the wealthiest part of the Richtersveld, as Namaqualand’s northwestern corner is known. The British annexed it in 1847, rolling it neatly into the Cape Colony. Alex Bay itself was inaugurated nearly 80 years later as a binnekamp – a ring-fenced, State-owned mining emporium where even policemen were refused entry for fear of there being raiders. Long the gem box of De Beers, which worked in league with the state, regional happiness has never been a priority.

“‘Little London,’ they called Alexander Bay,” wrote a journalist in 1967, “for at night the electric display and the searchlights throw into the sky a white glare that can be seen many miles away.”

Alex Bay can no longer muster much of a light show. It’s a strange mash-up of mining and marine town, a town inhabited by men and women who are either currently the hardest drinking people on earth, or who have found the Lord and have cut back somewhat. The tar roads long ago submitted to the encroachment of the desert, and the neighbourhoods appear to have been evacuated in anticipation of imminent invasion from the sea.

For the most part, the onshore diamond deposits have been mined beyond the point of profitability. Offshore, however, is a very different story. On the South African side, the big carat stones sit just off the river mouth. They’ve never been mined because of the effort and investment it takes to churn through the thick sediment.

“Offshore Namaqualand is the richest deposit of diamonds in the world,” insists Craythorne, “and this, here in Alex Bay, is the richest portion of it.”

But none of this wealth has entered the economy’s bloodstream, largely due to the usual story of government/corporate collusion that has defined South Africa since its modern inception.

Going Dutch

Marine mining is, at its most basic, gambling in a wetsuit. Find a significant stone and you’re set for life. Fail to do so, and you’re little more than a human crayfish.

In 2005, Gavin Craythorne began modifying an innovation developed by a treasure hunter named Mel Fisher. In the mid-80s, Fisher located a sunken galleon by installing a box over his boat’s propeller, which directed enormous pressure downwards in order to disperse the sand and sediment hiding the wreck. This was Craythorne’s Eureka moment, and he christened his blowing vessel “Ocean Digger”. The rig took years to perfect, but its successor, “Ocean Heritage”, is equipped with a 250kg anchor and a 450 horsepower engine that pushes ten tons of water per second through a nozzle. He is now able to excavate down to depths of 22 metres through three metres of sediment. (He’s subsequently patented the system, dubbing it Mass Flow.) Think of it as a huge hairdryer that blows shallow trenches into the sea floor, scooping up diamond-rich sediment for sifting either on board, or at an onshore processing plant.

Along with 80 or so other mining contractors, Craythorne forms an integral part of the local economic ecosystem. But despite all the ingenuity and money invested in his mining operations, his rig sits rusting in a dock. Towards the end of 2017, he and a ragtag group of contractors were locked out of the only game in town – the state-owned mining enterprise Alexkor – for whistle-blowing levels of corruption and mismanagement that are astonishing even by South African standards.

As such, Namaqualand suffers from a brutal case of Dutch Disease. As a result, the region is bubbling with discontent. Team Ramaphosa’s star quarterback, the newly installed Minister of Public Enterprises, Pravin Gordhan, recently told Parliament that Alexkor will soon be the subject of a forensic investigation. At the very least, the department will learn that the gravitational pull of Alexkor’s dying star is so considerable that Namaqualand remains a mining enclave with almost no upside for anyone but upper management, government hacks, and the usual corporate goons.

The National Development Plan 2030, which serves as the government’s overarching policy framework, was designed to filter down to local levels in the form of so-called “integrated development plans”, which were in turn was supposed to generate economic blueprints in regional contexts. In Namaqualand, there is only Alexkor, which has sucked the life out of economic diversification. Even the fishing industry’s growth has been existentially impaired, because the Northern Cape has no commercial harbours. (The Western Cape has 15.)

“There’s no participatory development here,” says Craythorne. “There’s no NDP for us.”

Alexander Bay street (Photo by Richard Poplak)

The Leviathan

The mutant underwater sea monster called Alexkor was established in 1992, caged in the ruins of a shitty apartheid-era corporation that was also magically unable to turn a profit. Its current mandate is simple: to transform, nurture and grow the economy of Namaqualand. According to the Department of Public Enterprises:

“The core business of Alexkor is the mining of diamonds on land, along rivers, on beaches and in the sea along the north-west coast of South Africa.” (The department ignored numerous requests for comment, and can you blame them?)

While its operations are based in Alexander Bay, Alexkor was until recently headquartered in Rosebank, Johannesburg. In true Alexkor style, the company illegally broke the lease on these premises, incurring a R2.9-million penalty. It is now conveniently located in Woodmead, a mere 1,388km charter flight from its base of operations.

If Alexkor is an experiment for mining nationalisation in South Africa, then let’s just say that socialism performs no better than capitalism does around these parts. A combo of Soviet-style somnambulism crossed with drug den economics, the company is a revolving door for African National Congress (ANC) cadres both on the board and in management, with a performance record that is commensurately atrocious. The company lost R82-million in 2015, R36-million the following year, and is currently carrying an accumulated loss of R78.7-million. In 2017, according to the auditing firm SizweNtsalubaGobodo, R17.9-million evaporated due to the fine art of “fruitless and wasteful expenditure”.

There is no proper record keeping, no regular performance reports and, according to the auditors, no “effective oversight responsibility over certain policies and procedures relating to supply chain management, performance management, revenue, compliance, and related internal controls”.

In an email to Daily Maverick, the company attributed these failures to the fact that it was a) governed by acting Chief Executive and Financial Officers over the course of 2017, b) the diamond resources in the region are dwindling, and c) it had onerous corporate social responsibility commitments.

“We are confident that the new team is addressing the issues […] and that the 2018 audit will comment favourably on progress,” noted a spokesperson.

We’ll just have to see about that. The current CEO, Lemogang Pitsoe, has been in the position since late 2017, and was appointed by former Public Enterprises minister Lynne Brown – which should be enough to send any analyst leaping from a 20th floor window. Indeed, Pitsoe helped celebrate the infamous Gupta wedding in Sun City, and served as General Manager of Hernic Ferrochrome, which went into business rescue in 2017, resulting in the retrenchment of 700 employees.

Meanwhile, Hantsi Matseke, the company’s chairperson, has excellent air cover within the ANC due to a longstanding relationship with Ace Magashule, the former Free State premier currently serving as the party’s secretary-general, for whom she ran the Free State Development Corporation (FDC). Leaving aside the infamous Estina dairy debacle, Matseke was recently implicated in a scandal in which the FDC scored a R9-million property deal payday for Magashule’s daughter – a scam that put 60 locals out of work.

There is pretty much nothing that Alexkor has got right, ever. Take, for instance, this epic story, which should have been one of the most glorious episodes of the post-apartheid era. In 1998, the Richtersveld community, somewhat miffed by the results of 400 years of colonialism, began a long legal tussle with Alexkor. Using the 1994 Restitution of Land Rights Act, they fought for a narrow 120 kilometre-long strip of formerly communal land along the west coast, which had been mined for generations.

Happy ending? Almost. While the community lost in the Land Claims Court in 2001, they took the case to the Supreme Court of Appeal, and won. In 2003, Alexkor and the government attempted to reverse this decision by going to the Constitutional Court. A full bench upheld the Supreme Court of Appeal’s ruling, resulting in the Richtersveld community making history. As the analyst David Smith noted:

“It was a monumentally important case […] because it was the first case to consider the customary law of indigenous peoples and set a precedent that allowed many more indigenous people to access land that they had been disposed of under white rule.”

So far, so good.

But – and it’s a big but – the land was worth R10-billion, the state couldn’t afford to purchase it, and so a deal was forged. The land mining rights accrued to the community, and Alexkor retained the marine mining rights; a deed of settlement was drawn up, and a Pooling and Sharing Joint Venture (PSJV) was created. The joint venture, called Alexkor/RMC JV, was 51% owned by Alexkor, 49% by the Richtersveld Mining Company, and run by its own governance board – a complicated mechanism, designed to reverse the ills of colonialism, that has done no such thing. Compounded by a corporate social responsibility programme that isn’t responsible, and a social labour plan that includes very little labour, the relationship between many in the community and the leadership of the joint venture has turned dangerously toxic.

But the most recent controversy pertains to – who else? – the Guptas. In 2017, it was reported in these pages that Alexkor was using a company called Scarlet Sky as their sole diamond marketer. (In the industry, marketers do the actual selling of diamonds through a process called “tendering”.) The links between Scarlet Sky and Gupta factotums were made clear in the Scorpio/amaBhungane investigation. But the most obvious issue was the fact that Scarlet Sky was an untested company, one of its two directors had zero diamond experience, and that it was clearly set up to bid for – and win – the tender.

For its part, Alexkor vehemently denies any wrongdoing:

“Please wait for the outcome of the investigation before accepting that there is corruption at Alexkor,” wrote Company Secretary, Raygen Phillips, in an email.

“[We] welcome the investigation for the name of Alexkor and the PSJV to be cleared, as all of these allegations are putting a damper on the reputation of Alexkor in the diamond industry. For years Alexkor was known for its ‘sexy diamonds’, but since [the Scorpio/ amaBhungane] article everybody is questioning the reputation all of us [built] for many years. The effect of this will be that the innocent contractors of this mine as well as all our employees will at the end of the day be the [ones] affected negatively, as it takes years to build a good reputation.”

There is, however, one metric that Alexkor cannot spin: the price at which the company’s diamonds are sold compared to fair market value. When mapped on aggregate across all grades lower than six carats, and since the financial crash in 2009 (when Alexkor’s selling price lined up exactly with fair market value), the state-owned enterprise has consistently received about $450 less than the market price. That’s a 30% haircut over eight years – an estimated minimum loss to the taxpayer of R1.5-billion – that can be explained only by under-reporting, theft, or staggering negligence. What’s more, none of this accounting includes the big, 6.8-carat and larger stones, for which Alexkor doesn’t provide data.

Factor those in, and the estimated shortfall rises to at least R4-billion.

Alexkor is by no means exceptional in this regard: the diamond business is sleazy beyond the ability of words to convey, and nowhere is it sleazier than on the marketing side. With the occasional outlier, and dating back long before the democratic era, Alexkor has had a history of working with dirty marketers. Scarlet Sky fits the picture. Some industry observers describe it as the “Angolan model”: force miners to sell to state trader, force them to sell below market through a crooked marketer, and the diamonds spirited off to Whereversville.

“They guard the marketing with their life,” said one industry insider, who did not want to be named for obvious reasons. “If Pravin [Gordhan] actually wants to do something, he has to normalise the marketing channel immediately. Everything else about Alexkor is a red herring.”

Death by acronym

Gavin Craythorne’s low-slung mining-town bungalow serves as an ad hoc headquarters for contractors locked out of Alexkor. Their loosely defined organisation is called Equitable Access Campaign, and along with industry veterans George Nicolaai and Joseph Klaase, we watch marine traffic inch across a digital ocean. The Automated Identification System, a ship-tracking site, shows a cluster of vessels working the deep-water concessions on the Namibian side of the border, pumping hundred of millions of dollars a year into national coffers. On the South African side, there’s just a single ship plying the lonely e-waters. As for the delta, there’s no activity at all. If anyone were looking to explain why the South African economy contracts while the rest of the world booms, this would be one of the places to start.

Earlier, Craythorne conducted for me a lesson in marine mining 101:

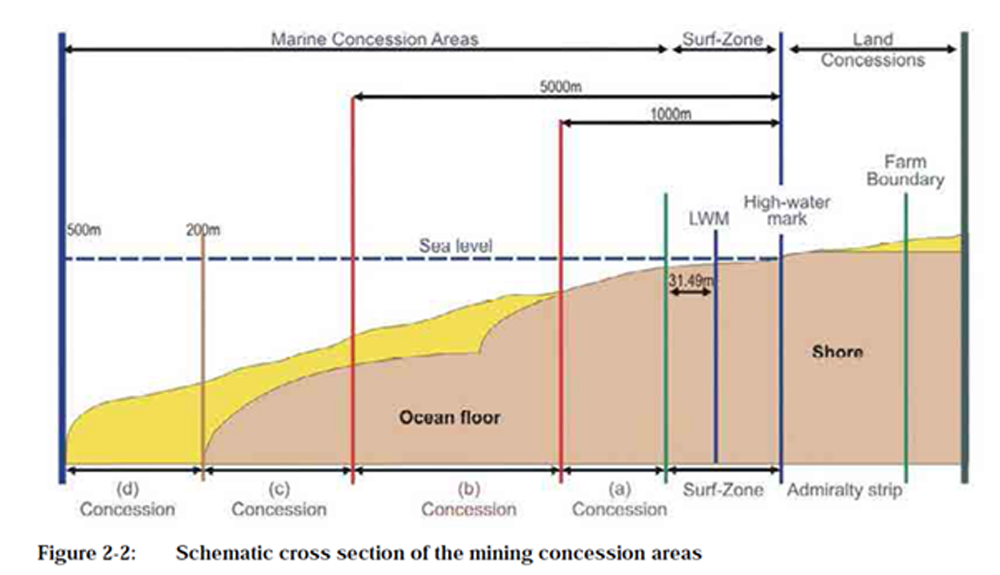

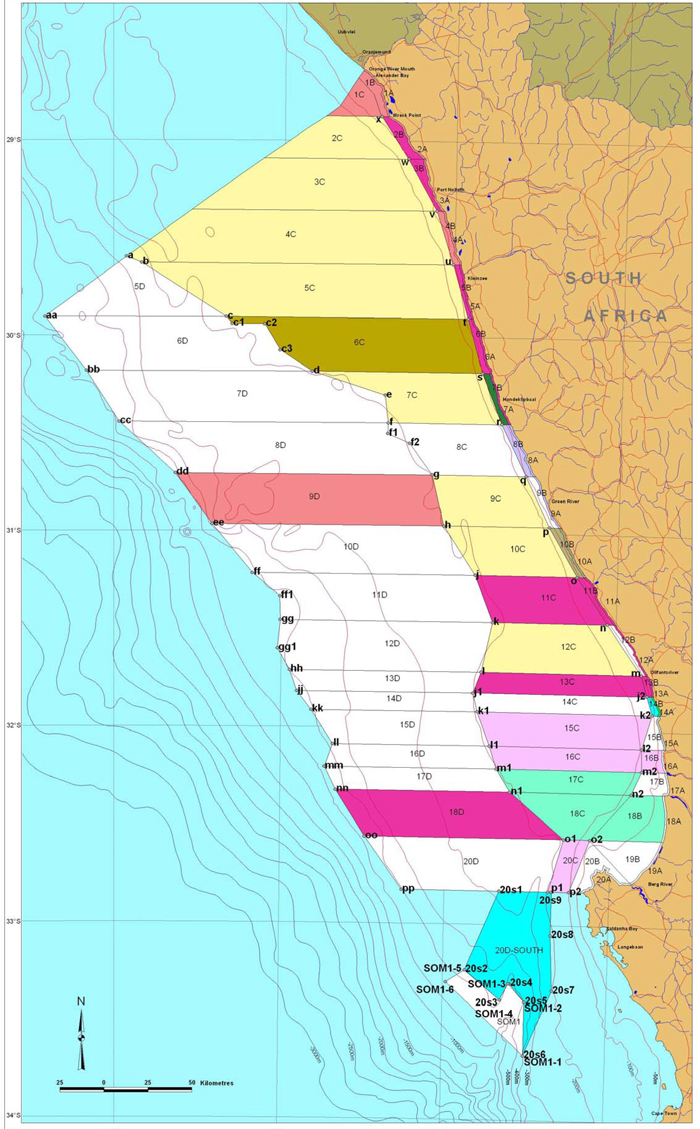

“There’s the beach, the surf zone, the mud belt, and then the ocean bed, successively,” he explained. “The concessions in Northern Cape waters are not easy to track, but roughly speaking, they run in diagonals, and are divided into numbers, and then into letters.”

Historically, these concessions have been mined by a mix of large and small operators – sometimes just a guy in a speedo wielding a shovel. And not all concessions are created equal – some are un-mineable, and even De Beers doe not possess the tech to churn through the mud belt any deeper than four meters. A regular operator can’t get loans for this sort of equipment, and nor can it be purchased off the shelf. The whole endeavour requires major, sometimes life-destroying, investment.

Alexkor, in an email to Daily Maverick, said that it works with “89 contractors for land mining, beach mining, shallow water marine mining, middle water mining and deep sea mining”.

Equitable Access Campaign estimates that this results in work for about 400 to 800 people, while Alexkor insists that it employs 1,300 “directly and indirectly”.

“The tragedy of it all is that if you look at the Northern Cape marine mining industry, if it was flourishing, it would be directly employing between 5,000 and 10,000 people. And that’s why the local economy is in a perpetual recession,” says Craythorne.

According to the small contractors, the major problem is fair access. Alexkor’s contracts stipulate that smaller contractors working their concessions accept a 52/48 revenue split in favour of the state-owned enterprise, even though the miners put up all the risk. Because of the possibility for theft, Craythorne and his crew aren’t allowed to sort and grade diamonds at sea. (And make no mistake, small contractors are not always as religious- and civic-minded as the Equitable Access crew.)

In order to avoid leakage, Alexkor controls the entirety of the production plant process for its small contractors. If anything, given Alexkor’s record, this exacerbates leakage.

“We know they’re stealing diamonds in the plant,” Craythorne tells me. “They won’t polygraph the guys in the plant” – polygraph tests for contractors and employees are standard in the diamond business – “and they won’t provide us with data on the grades. They would never let us follow our product through the value chain.”

Alexkor told Daily Maverick that it performs polygraphs on security personnel, and that “the PSJV is maintaining a stringent security control system at all of its diamond processing and recovering plants”.

That said, due to the lack of transparency, everything just disappears into the company’s amorphous bottom line. Nothing is trackable, and no one is accountable.

“Confront Alexkorp management on these issues, and they close the mine gate on you,” says Craythorne.

And then there are the uncontrollable uncontrollable, most notably the weather. A sea day is defined by clemency agreeable enough for 50% of local vessels to be on the water. The mitigating factor is underwater visibility – or “viz” in the parlance – which is spoken about in mystical terms. (A maxim: choppy sea kills viz.) Once, not so long ago, a West Coast marine miner could expect 150 sea days a year. In 2003, that began to change, and in 2011 that number was reduced to 13.

“The window for the industry up here,” warns Craythorne, “is closing. And quickly.”

Anatomy of a Monopoly

At the present moment, 77% of the viable concessions on the Northern Cape coast appear to be dormant. (Alexkor would not comment on this number.) The ownership of those concessions, and who holds the rights to mine them, is where the classic South African stitch-up comes starkly into view.

Outside of De Beers, the most prominent corporation working the littoral is called Trans Hex Group. This is an apartheid-era hangover, established in 1965 in order to prospect state-owned land in Namaqualand. Flush with cash due to the regime’s largesse, the company went on a buying binge, finally listing on the JSE in 1980. In 2014, Trans Hex was purchased by a consortium led by mega-investor (and chief Steinhoff patsy) Christo Wiese, whose Magenta Cream and Metcap Proprietary Limited, along with Piet Viljoen’s RAC investment Holdings, own 76.74% of the company.

According to industry observers, Trans Hex is poorly managed, and that’s perfectly reflected in its financial literature. Capitalism’s default cure for shitty performance? Get bigger and consolidate. In 2012, even before Wiese came on board, Trans Hex “partnered with investors” (more on them in a minute) in order to form West Coast Resources. The company forms a nice corporate précis of the way business is done out here. It is majority-owned by the Trans Hex Group, while Public Enterprises (AKA you) owns 20%, a BEE front called Dinoka Trust Holdings owns 8.8%, and the Namaqualand Diamond Trust 4.4%. In a tidy little reach around, West Coast Resources contracts Trans Hex “to manage the Company’s operations and to market the diamonds it produces”. It’s a closed fiduciary loop, one that has until recently escaped the interest of the Competition Commission.

But the reach around doesn’t stop there. The other corporate killer whale patrolling the littoral is the IMDH Group, an offshore mining and geological surveying company. The local operating division is called International Mining and Dredging South Africa (IMDSA), and guess who contracts them to run their offshore mining operations?

Alexkor, of course.

IMDSA, based in Cape Town, also has a Wiese connection – he owns 10% of the company. But unlike small producers, IMDSA gets an 85/15 split with Alexkor. Both IMDSA and Alexkor claim that this is on account of the high costs of its deep-sea operations. Fair enough. But it puts into stark relief the exploitation smaller contractors are subjected to.

Far worse, at least as far the environment is concerned, is Alexkor’s reliance on a single contractor in order to conduct environmentally devastating (and likely illegal) sea-wall or coffer dam mining. The company is called Ambicor, and its “managing member” (according to his LinkedIn profile) is Jaco van Niekerk. Think of coffer dam mining as building large underwater walls on the ocean bed, and then dredging the sea-floor into oblivion. Ambicor employs explosives and heavy equipment in order to quarry big chunks of rock onshore, which are then dumped in the ocean to form the dams.

Not only do the walls destroy the ocean bed, they also send particulate matter into the water, badly impairing viz. While De Beers, Alexkor and Trans Hex (who are also enthusiastic proponents) insist that the walls “self-rehabilitate” – meaning that they slowly dissipate over time – it doesn’t take an environmentalist to acknowledge that boulders don’t walk themselves back to the beach.

At the very least, the process flouts the rehabilitation requirements of the Mineral and Petroleum Resources Development Act and the National Environmental Management Act, while Alexkor itself has admitted to working off an outdated environmental assessment report from 1995, which in any case states that “under no circumstances should gravel, cobbles or boulders be used in coffer dam mining operations”.

The abiding question on the Namaqualand coast is why Alexkor is so amenable to these White Monopoly Capital monstrosities, when its mandate as a state-owned enterprise, at least according to the National Development Plan, should be to support and grow the small-to-medium-sized business sector. Part of the answer lies in the fact that the government has effectively – deliberately? – turned a blind eye to what has been transpiring up here.

And another part of the answer lies in the fact that Trans Hex CEO Llewellyn Delport, and Alexkor/RMC JV CEO Mervyn Carstens, “have always hunted in a pack”, as one insider told Daily Maverick. Carstens is a former Trans Hex executive, and was a shoo-in to take over the Joint Venture after running a now defunct Trans Hex mine called Baken. Thus, the line between industry and government is all but non-existent, a coziness that has not resulted in good governance for either entity.

Peak Empowerment

The vector to wealth for ANC cadres in the Northern Cape has for two decades been the age-old diamond group, De Beers. And while De Beers didn’t invent monopolisation and State Capture, they certainly perfected it. In the early 2000s, there appeared to be a plan to merge their local properties with Alexkor, linking up a long line of operations with their Namibian-based Namdeb operations. This plan was interrupted by the Richtersveld land claim, and the fact that Trans Hex – an ostensible competitor – began populating the management of the Pooling and Sharing Joint Venture. Outfoxed, De Beers and its partners then looked to offload their local land deposits, selling to West Coast Resources their Namaqualand Mines property in 2014.

That same year, a company called the Questco Consultancy Group drafted a report, which slowly leaked out to the press and other interested parties. Questco’s plan was to develop an interweaving consolidation of the local diamond industry, with something in it for all the big players. It goes something like this: Trans Hex and West Coast Resources, along with the PSJV management, would come to own the bulk of the diamond concessions, with De Beers using their deep sea marine mining experience to work the farthest waters. Alexkor would exit the diamond business to concentrate on “strategic minerals” – like, for instance, coal [insert five billion laughing emojis here] – and the government’s share would be vastly reduced.

One day soon, the Questco report will be regarded as the greatest work of art in the history of South Africa, largely because it depicts the country’s corporate reality in pointilist detail. Until then, the fear is that, following Gordhan’s forensic investigation – which will no doubt reveal an Eskom-in-miniature horror show – Public Enterprises will break up Alexkor, sell off the concessions at well below market value, and the diamond industry along the coast will belong to only a couple of players, including a man who couldn’t keep a furniture conglomerate from devolving into a Ponzi scheme.

In other words, whether under Zuma The Bad or Ramaphosa The Benevolent, the Questco report could end up being a self-fulfilling prophecy: further monopolisation; further enabling the corporate/ANC death march to penury; further doubling down of big contracts to big contractors; further crippling small business in Namaqualand.

Uprising

“We’re going to make fire there,” Lydia Obies tells me, over a friendly cup of tea in Gavin Craythorne’s living room. “We’re tired of this.”

Lydia Obies and Annemarie de Wet are two fearsome women who belong to an 11-person organisation called the Community Property Association (CPA). They are not happy. The Alexkor/RMC JV is meant to benefit them, but they claim it does the opposite.

“We see nothing from them,” Obies spits. “The community sees nothing.”

In an email to Daily Maverick, the joint venture CEO, Mervyn Carstens, laid out the standard tragic scenario that allows mining companies to slice through communities across the world:

“The Richtersveld community has historically been plagued with divisions and factions,” he wrote. “The current leadership has been embattled in various court cases over years amongst themselves and different factions within the community.”

Divided and conquered, in other words.

A Western Cape High Court judgment ruled that the current governance structures of the CPA has expired. And so unfolds a huge Catch 22: Alexkor can claim it doesn’t know who the legitimate representatives of the community are, and can therefore refuse to put community members on the board. Meanwhile, CPA can’t access the funds due to it, because it doesn’t have the money to put in place regularised governance structures.

Under Obie’s administration, the CPA no longer receives any financial disbursement. According to Obies, Alexkor no longer replies to letters. The relationship has all but broken down. And while the violence hasn’t got out of control yet, Alexkor management has received death threats so filthy that they’re unprintable. This is not a clean war.

The end looms with the forensic investigation, and the serious notes the Ramaphosa administration has sounded regarding State Capture. But Alexkor goes way beyond cute buzzwords. The company is the bastard super-child of colonialism and apartheid, and its legacy has never been addressed by the ANC. If anything, it’s been maintained and deepened. Pravin Gordhan couldn’t have picked a better place to start Ramaphosa’s reinterpretation of South Africa, but he’ll have to unpick both the knots that bind the region to Stellenbosch old money and BEE new money, none of which trickles down. They’ll need new maps. The old ones have no viz.

“We have a sense of history here,” Craythorne tells me, before I leave.

“We believe in the David and Goliath possibilities. The prize is big. We can see it.”

No one here has ever had any trouble seeing the prize. That’s been Namaqualand’s curse for generations. DM

Become an Insider

Become an Insider