SassaGate

The SA Social Security Agency and Bathabile Dlamini’s gift to White Monopoly Capital

If the Sassa/CPS/Net1 social grants saga were a Hollywood heist movie, former Minister of Social Development, Bathabile Dlamini, would be a shoo-in for the role of the driver of the getaway car. With CPS pleading poverty and near-ruin, the likelihood of the company repaying to SA Social Security Agency (Sassa) a R316-million windfall it received from former Sassa CEO Virginia Petersen seems remote. Will White Monopoly Capital ride off into the sunset with bulging saddle bags?

One thing former Conservative British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher and former Minister of Social Development, Bathabile Dlamini, have in common, apart from being women that is, is their fierce fealty to privatisation.

Under Dlamini’s almost decade-long watch, it was goodbye Radical Economic Transformation and hello private corporate profits. The twist in our tale is that these profits were made off the backs of the most vulnerable in South Africa, those who depend on social grants to stay alive.

It is a humungous tender worth R10-billion a month, the kind of steaming pile which attracts a hungry swarm of keen profiteers.

Cash Paymaster Services has had an enchanted run in spite of ConCourt rulings against it. The company’s illegal tender to pay social grants was extended three times to avert Sassa and Dlamini’s “self-generated” national catastrophe in April 2017, when the contract was meant to come to an end.

The crisis continued into March 2018 when the contract was extended again after spectacular incompetence on the part of Sassa. Perhaps one should not be so harsh, as Dlamini had created parallel “work streams” inside Sassa, staffed by hand-picked advisers (who earned millions) and ostensibly aimed at helping the agency take the payments of grants in-house but which, instead, seemed to thwart the process at every turn.

The narrowly averted crises courtesy of Dlamini could have scuppered one of the governing party’s most crucial flagship programmes – the provision of social grants to 17 million poor South Africans.

From the start, Net1 and CPS intended to use the tender to sell financial and other services to grant beneficiaries. This was clearly set out in its original 2012 business plan with CPS’s original BEE partners, Born Free Investments 272, Ekhaya Skills Developments Consultants CC and Retles Trading CC.

Part of this Service Level Agreement required Sassa to grant CPS “the right to provide value-added services, such as the sale of prepaid utilities and the provision of financial services, such as money transfers, credit facilities, insurance products and debit orders to all beneficiaries”.

The clause never made it to the final contract but it does provide a lovely Freudian insight into the recesses of the Net1 business model.

Despite the Act, Sassa signed the agreement. Shortly after being awarded the tender, CPS dumped its 2011 BEE partners and opted instead for Mosomo Investments Holdings, whose CEO, Brian Mosehla, scored R83-million in the deal.

Mosehla and Dlamini shared a mutual friend, Lunga Ncwana, who acted as a bagman for Brett Kebble and his generous donations to the ANC.

Net1/CPS have been embroiled in a number of court applications since the awarding of the tender in 2012, its declaration by the ConCourt as illegal in 2014, right through to the continued extension of the contract until September 2018 when CPS will ride off into the sunset.

But will those saddle bags be empty or bulging with a R316-million windfall the company was gifted by the Sassa CEO, Virginia Petersen, in 2014?

In March 2018, the North Gauteng High court, in an application brought by Corruption Watch in 2015, ordered CPS to repay R316-million. CPS claimed the amount was owing for the enrolment of additional – around 11 million – grant recipients and beneficiaries over and above the total quoted for in the original contract with Sassa.

Handing down judgment, Judge Moroa Tsoka said that it was Sassa’s unlawful conduct that had resulted in the fiscus being “robbed of a substantial amount of money intended for the most vulnerable and poor of our country”.

It was “just and equitable”, he added, that the money be returned to the fiscus “for the benefit of those for whom it was intended in the first place”.

Net1 UEPS Technologies, the US based parent company of CPS, immediately applied to the High Court to appeal the ruling, but lost. The company petitioned the Supreme Court of Appeal last week.

However, one way to settle the matter, according to Leanne Govindsamy, Corruption Watch head of legal and investigations, would be for CPS to repay the R316-million to Sassa and then claim it back later after gathering and showing proof of the work done.

Simple and clean, n’est-ce pas?

For now, CPS is pleading poverty.

CEO Herman Kotze wrote to Chief Justice Mogoeng Mogoeng on 23 May in relation to another matter – the fee CPS wants to be paid for the remainder of its extended contract with Sassa – claiming that the company only had sufficient cash reserves to cover its operations costs until 31 May 2018, “assuming Sassa duly pays its invoice for March 2018”.

A recurring sticking point with regard to CPS and Net1 is just how much profit has been raked in from the repeatedly rolled-over contract with Sassa and from the “sale” of other services, including loans, to beneficiaries.

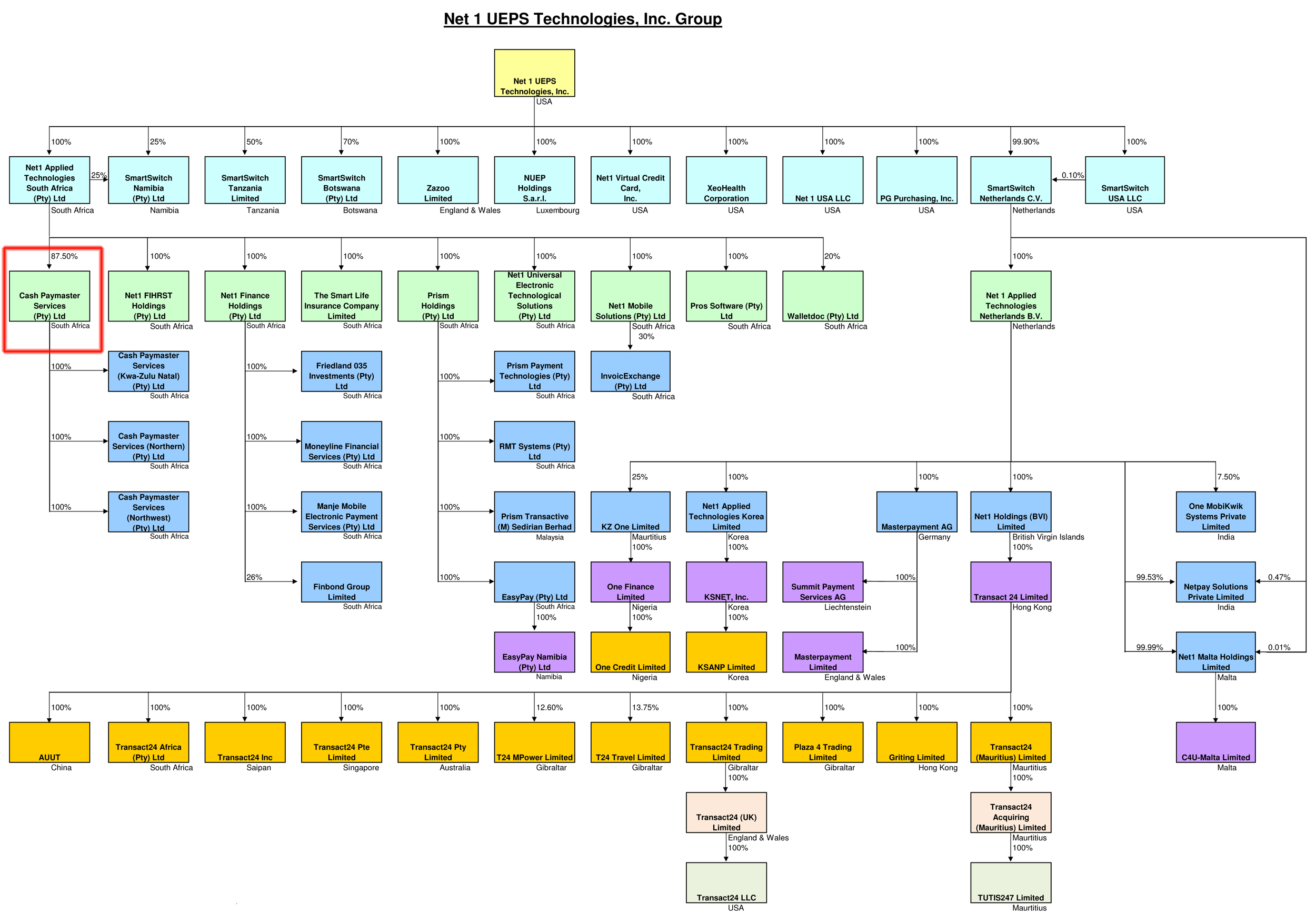

What muddies the waters is the fact that CPS is one entity of 21 in South Africa (and 60 internationally). CPS also pays a “royalty” to Net1 or one of its subsidiaries.

It is helpful to turn to the 16 November 2017 report by the court-appointed Auditor General and Panel of Experts to the ConCourt and which conducted a financial assessment of a 12-month period of payments.

The AG and the panel found that Sassa continued to pay CPS R14.42 plus VAT per recipient paid, a fee which generated close to R2-billion of revenue for CPS.

“Over the term of the five-year contract, CPS earned over R1-billion of operating profits. These profits are net of patent and licence fees paid to CPS’s parent company Net1, which also exceeded R1-billion over the period.”

Most of CPS’s other costs, said the panel, were incurred for the payment of cash to beneficiaries at CPS pay points.

“The panel has calculated that cash distribution from CPS pay points cost around R50 per beneficiary. Despite most payments being made electronically to beneficiaries, CPS’s core operational activity is ‘a logistical business distributing R2.3-billion of cash in rural areas each month’.”

There were, the panel added, three additional revenue streams earned by CPS/NET1 in relation to Sassa beneficiaries.

These were:

-

interest earned on grant funds received from National Treasury;

-

bank charges levied on beneficiaries for using non-CPS ATMs and other banking services, for both the Sassa card and EPE card; and

-

sale of financial and insurance products to beneficiaries.

“The issue of interest was first raised with the panel by Advocate Paul Hoffman SC, who represents the Quaker Peace Centre, a non-profit organisation. In a letter to the panel, Advocate Hoffman expressed concerns that CPS/Net1 and Grindrod were deriving interest illegitimately from grant funds. Advocate Hoffman referred to statements made by former Finance Minster Pravin Gordhan at Scopa regarding the accrual of interest of funds that flow between Treasury, Sassa, CPS/Grindrod Bank and grant recipients each month.”

As some beneficiaries did not access their grants on the beneficiary payment date, interest is earned by CPS/NET1.

“The panel understands that several days prior to payment date, funds are transferred from the National Treasury (via the Department of Social Development and Sassa) to CPS’s Nedbank accounts in each province. On payment day, the funds are transferred to the Grindrod holding account, registered in Net1’s name. Funds are retained in the holding account until the beneficiary withdraws either through a CPS pay point, ATM or POS device. As most beneficiaries take up to five days post payment date to withdraw their funds, interest accrues in the holding account,” said the panel.

CPS had confirmed that all interest earned from its Nedbank accounts were refunded in full to Sassa during the monthly reconciliation process.

However, interest accruing in its Grindrod holding account was retained and shared between Grindrod and Net1 on a 50/50 percent basis.

“CPS argued to the panel that it is entitled to this interest as it incurs banking costs on behalf of beneficiaries. However, the panel understands that some of the banking services (i.e. card issuance, the provision of pay points etc) are provided as part of the service level agreement between CPS and Sassa and, accordingly, the costs of these services should be recovered from the R14.42 fee charged to Sassa. Also, many of the banking services or access to facilities that are not covered under the SLA are charged to beneficiaries according to CPS’s transactions fee schedule.”

The panel noted that under the service level agreement with Sassa, CPS is obliged to refund all unclaimed grant funds with interest, and this requirement applied regardless of banking fees incurred by CPS.

“The value of interest earned by Net1/CPS under the Sassa contract is not directly observable as the NET1 listed company reports consolidated interest revenue for all of its divisions. In its Annual Financial Statements, CPS does not disclose interest income from grant funds separately.”

Instead, CPS stated that “the exposure to interest rate risk is high due to the cash received from the South African government that the group holds pending the disbursement to recipient cardholders of social welfare grants”.

This disclosure of interest rate risk, said the panel, reflects the impact that a change in the South African repo rate has on CPS’s interest income.

“CPS stated to the panel that up to 80% of grant funds are claimed within the first four days following payment day. CPS disclosed to the panel that Net1 SA earned R49.9-million of interest for the year ended 30 June 2017 from its Grindrod holding account.”

In addition to earning interest on income on grant funds, Net1/CPS earned “significant income” from bank fees charged to Sassa beneficiaries.

Beneficiaries were charged for withdrawals using ATMs of any bank other than a Net1 ATM. Fees were also levied on other ATM services such as balance inquiries, cancelled transactions, invalid PIN and insufficient fund notification.

“All bank charges are levied by Grindrod (i.e. deducted from beneficiary bank balances) and the revenue from these charges are passed on to CPS.”

CPS had confirmed that it earned R1-billion in fee revenue from Sassa cardholders for the provision of National Payment System ATM infrastructure and the provision of the Net1 ATM services for the year ended 30 June 2017.

This was in addition to the revenue earned under the Sassa contract.

The bulk of fee revenue was derived from transactions carried out at ATMs connected to the NPS that are not owned or operated by Net1.

“CPS argues that these are fees ‘charged in accordance with the various fees determined by the SARB’ and cover the costs of ATM interchange fees. The panel is unable to determine the profit CPS derives from bank fees after taking account of ATM interchange fees; the panel has requested this information from CPS. The panel analysed Net1 financial disclosures to the US Securities and Exchange Commission which shows revenue and operation profit for Net1 South African transaction processing division.”

This division comprises the Sassa contract, the provision of ATM infrastructure (both Net1 and ATMS) and transaction processing for retailers, utilities and banks (EasyPay).

“The reported operating profits of this division are significantly higher than the operating profits disclosed by CPS’s management accounts for the Sassa contract only. Although much of the difference may be accounted for by the profits for the EasyPay business, the panel remains concerned that Net1 may be earning significant operating profits from bank fees charged to Sassa beneficiaries.”

The most recent ATM interchange fee structure provided by the Payments Association of SA (PASA) showed that an issuer bank paid R3.48 and 0.53% of the withdrawn amount for the use of NPS infrastructure. For a R1,500 withdrawal this equated to an “interchange fee” of around R14 inclusive of vat, compared to the R18.84 CPS charged to beneficiaries for the same amount.

“The Net1 financial disclosures show that the financial inclusion and applied technologies division derived R3.2-billion of revenue and a R787-million operating profit for the year ended June 30, 2017. This division includes revenue and profits from the provision of short-term loans, the sales of electricity and airtime and the sale of insurance products,” noted the panel.

It was not possible to determine the portion of the revenue and profits from this division that is derived from Sassa beneficiaries, said the panel, “as there are other components within this division that relate to the maintenance of smart cars and the sales of hardware and software”.

The panel noted its concern that Net1 derived “significant financial benefit from Sassa beneficiaries for services unrelated to its core transaction processing business”.

Justice Johann Froneman, in his 14 April 2014 order that the CPS/Sassa contract was illegal, ordered that CPS file “within 60 days of the five-year period for which the contract was initially awarded” an audited statement “of the expenses incurred, the income received and the net profit earned under the completed contract”.

Sassa too was ordered to obtain an independent audited verification of the details provided by Cash Paymaster and file an audited verification with this court.

It took until May 2017 for CPS, through its auditors KPMG, to file a single-page audited statement to the Constitutional Court which reflected that CPS had recorded a pre-tax profit of R1.1-billion from paying social grants on behalf of the government.

Its after tax net profit was stated as R705-million, which translated to R141-million a year in profit to shareholders.

Dick Forslund, senior economist with the Alternative Information and Development Centre (AIDC), commissioned by the Black Sash Trust and the Centre for Applied Legal Studies to analyse the statements filed by KPMG on behalf of CPS, found that CPS had inflated costs to provide “a reduced picture of actual profits made from the Sassa contract”.

Forslund also found that CPS, together with other legal entities in the Net1 organisation with which CPS is vertically integrated and transacting, made greater profits from the five-year contract than disclosed to the ConCourt.

The AIDC report argued that the R117-million for the 2014 BEE deal “should not have been included as an expense in the CPS Statement to the Court”.

There had been “no justification”, said the AIDC, as to why the 2013/2014 BEE agreement should be recorded as a CPS expense.

A document filed by Net1 with the US Securities and Exchange Commission and dated 12 October 2013 refers to the R117-million expense that had been added in CPS’s statement.

The listing indicated that the amount was for competing for a new tender after the AllPay judgment and stated “Net1 UEPS, BVI, Mosomo and Net1 concluded an agreement headed ‘Relationship Agreement’ on 9 December 2013 in terms of which BVI acquired shareholding in Net1 UEPS”.

The Relationship Agreement provided for a share exchange mechanism in terms of which BVI could exchange the shares held by it in Net1 UEPS for shares in CPS.

Following the 2014 ConCourt ruling, Sassa had indicated that it had commenced steps towards the issuing of a new tender for the administration of social grant payments.

“The Parties are in agreement that it would be mutually beneficial if BVI holds shares in CPS, so as to bolster CPS’s tender submission in relation to its black economic empowerment scoring,” Net1 informed the US Securities and Exchange Commission.

“The CPS parent company Net1’s profit from the Sassa contract, as well as the profits of other Net1’s subsidiaries from the Sassa contract, extends beyond the scope of contracted fees from social grant distribution. This is not clarified in the statement, which instead endeavours to draw a sharp line between earnings made ‘under’ the contract and earnings ‘derived from’, the AIDC said.

Judge Froneman, handing down judgment in the matter in 2014, noted that “when Cash Paymaster concluded the contract for the rendering of public services, it too became accountable to the people of South Africa in relation to the public power it acquired and the public function it performs”.

This did not mean, said Justice Froneman, that Net1’s entire commercial operation “suddenly becomes open to public scrutiny”.

“But the commercial part dependent on, or derived from, the performance of public functions is subject to public scrutiny, both in its operational and financial aspects.”

Will South African taxpayers get back our R316-million? If we don’t, we know who drove the getaway car. DM

Become an Insider

Become an Insider