Special report

Justice isn’t always just. Just ask exoneeres at Innocence Network Conference in Memphis, Tennessee

None of the exonerees who journeyed to Memphis from all over the US travelled light. With an astonishing 3,501 years behind bars clocked up between them for heinous crimes they did not commit – including arson, murder, rape, and robbery – these “innocents” of all ages, stages, colours and creeds carried heavy emotional baggage. The majority also bore an enormous debt of gratitude to Innocence Network lawyers, some of whom had worked for years to secure their release. A former Soshanguve taxi driver, Thembekile Molaudzi, was there.

Carolyn Raphaely is a senior journalist with the Wits Justice Project (WJP) which investigates miscarriages of justice and human rights abuses related to the criminal justice system. The WJP is based in the University of the Witwatersrand’s journalism department and is partially funded by the Canon Collins Trust.

When Thembekile Molaudzi, the first African exoneree to attend an Innocence Network Conference in the US, joined about 200 wrongfully convicted men and women – including death row survivors – on the stage of the Peabody Hotel in Memphis, he discovered he belonged to a club he’d never have chosen to join. Not least, because the collective pain and suffering of its members was impossible to imagine and, at times, too much for the former Soshanguve taxi-driver to bear.

Molaudzi, 39, understood the trauma of wrongful conviction only too well after spending 11 years behind bars trying to convince anyone who’d listen that he hadn’t committed a crime but a crime had been committed against him. Finally, he made legal history in 2015 when the Constitutional Court overturned its own judgment for the first time, overturned his life-sentence and conviction for the 2002 murder of a Mothutlung policeman, and ordered his immediate release.

“In Memphis, I realised I hadn’t suffered alone,” the former Kgosi Mampuru inmate says.

“I was part of a large ‘family’ of men and women who understood what I’d been through. I understood very quickly that my ordeal was nothing in comparison to the innocent people I met there. Some of them had spent 26 years, 38 years, even 42 years in ‘exile’. There were many cases much, much worse than mine.”

None of the exonerees who journeyed to Memphis from all over the US travelled light. With an astonishing 3,501 years behind bars clocked up between them for heinous crimes they did not commit – including arson, murder, rape, and robbery – these “innocents” of all ages, stages, colours and creeds carried heavy emotional baggage. The majority also bore an enormous debt of gratitude to Innocence Network lawyers, some of whom had worked for years to secure their release.

United by a common bond of betrayal by a criminal justice system supposed to protect rather than punish the innocent, the sheer numbers of the wrongfully convicted congregated in Memphis – a fraction of more than 2,200 exonerations recorded by the US National Registry of Exonerations (NRE) since 1989 – provided proof positive of a problem still unacknowledged, mostly ignored and often denied in SA.

“I met wrongfully convicted people in all five prisons where I served my sentence,” Molaudzi says “and know I’m one of the fortunate few. There are countless people behind bars in SA who shouldn’t be there.”

Though anecdotal evidence suggests the problem is much more prevalent than most members of the Judiciary and the SA public would like to believe, neither the Department of Justice nor National Prosecuting Authority maintain records. However, the volume of letters, phone-calls and reports from inmates, their families and correctional officials received by the Wits Justice Project (WJP), the only SA organisation working in this space, suggests Molaudzi may well be right. “To err is human,” he says. “Errors and mistakes do happen.”

Barry Scheck and Peter Neufeld came to a similar conclusion 25 years ago when they established the first Innocence Project (IP) in New York. Aimed at proving the innocence of people on death-row using DNA evidence to reverse wrongful convictions, the IP subsequently spawned a network of 69 Innocence organisations across the country and the globe which provide pro bono legal services to people who, like Molaudzi, claim they’ve been wrongfully convicted.

The author with Innocence Project co-founder Barry Scheck

The Innocence Network Conference, held in a different American city annually and this year attended by about 500 lawyers plus exonerees and their supporters, is also an IP brainchild. Powered by the belief that if DNA can prove people guilty, it can also prove them innocent, innocence organisations have to date successfully exonerated 356 people – including 20 death row survivors – just on the basis of DNA evidence.

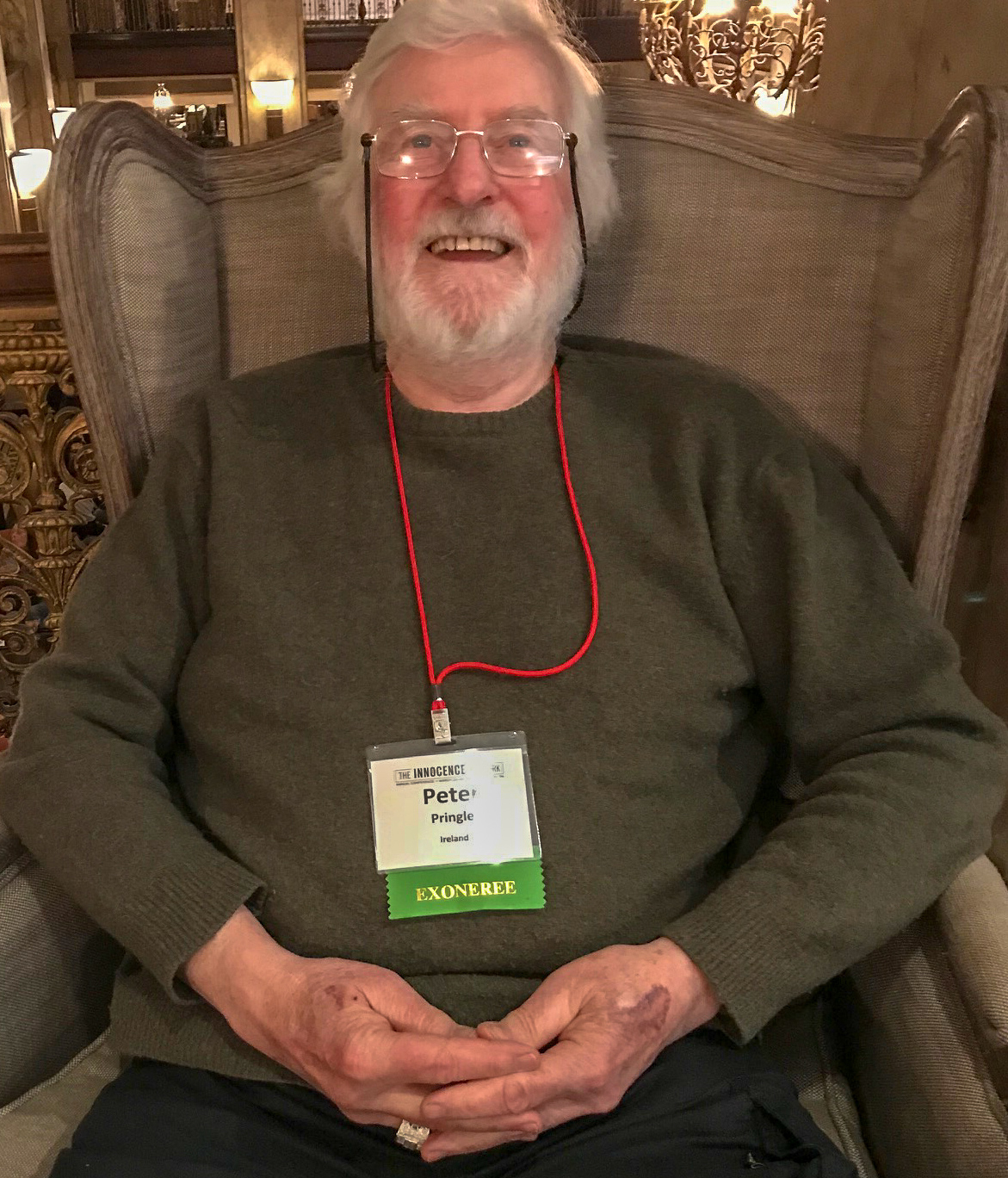

With the death penalty still legal in thirty-one American states – including Tennessee where the conference was held – Molaudzi knew only too well that he might have been executed, rather than exonerated, for a crime he never committed if SA hadn’t abolished capital punishment in 1995: “Every time I went to the clinic in Pretoria C- Max, I passed the gallows. Sometimes I was even sent to clean and dust there. I often thought it could have been me. That’s why hearing people like Peter Pringle talking about what he went through waiting to be executed, made me cry. I don’t think you ever recover from having a noose hanging over your head. And I saw the pain in that man’s eyes.”

Exoneree Peter Pringle

Pringle was one of the last people in Ireland sentenced to death for the murder of two policemen before capital punishment was abolished in 1990. His sentence was commuted to 40 years in jail without parole just two weeks before his execution date. After he became a “jail-house lawyer” and successfully pleaded his own case, he was finally exonerated, having been incarcerated for 15 years.

Prior to meeting and marrying his now-wife Sunny Jacobs, Pringle and Jacobs led curiously parallel lives – both faced the death penalty in different countries for similar crimes they both swore they hadn’t committed. Like Pringle, Jacobs was sentenced to death for the murder of two police officers. She spent five years on death-row in solitary confinement in a Florida prison before her sentence was commuted to life.

Though the quietly-spoken Jacobs escaped execution by a hair’s breadth, her co-accused and then husband Jesse Tafero wasn’t as lucky. Tafero died with his body in flames during a widely publicised botched execution resulting from a malfunctioning electric chair. After Tafero’s death, their third co-accused Walter Rhodes confessed to firing the fatal shots which killed the two policemen confirming both Tafero and Jacobs’ long-maintained innocence.

Jacobs’ 10-month-old daughter was an adult when her mother was released 17 years later. Molaudzi, whose son Mark was a similar age when he went to prison, could well relate. He wasn’t the only delegate reduced to tears by the couple’s tragic tale.

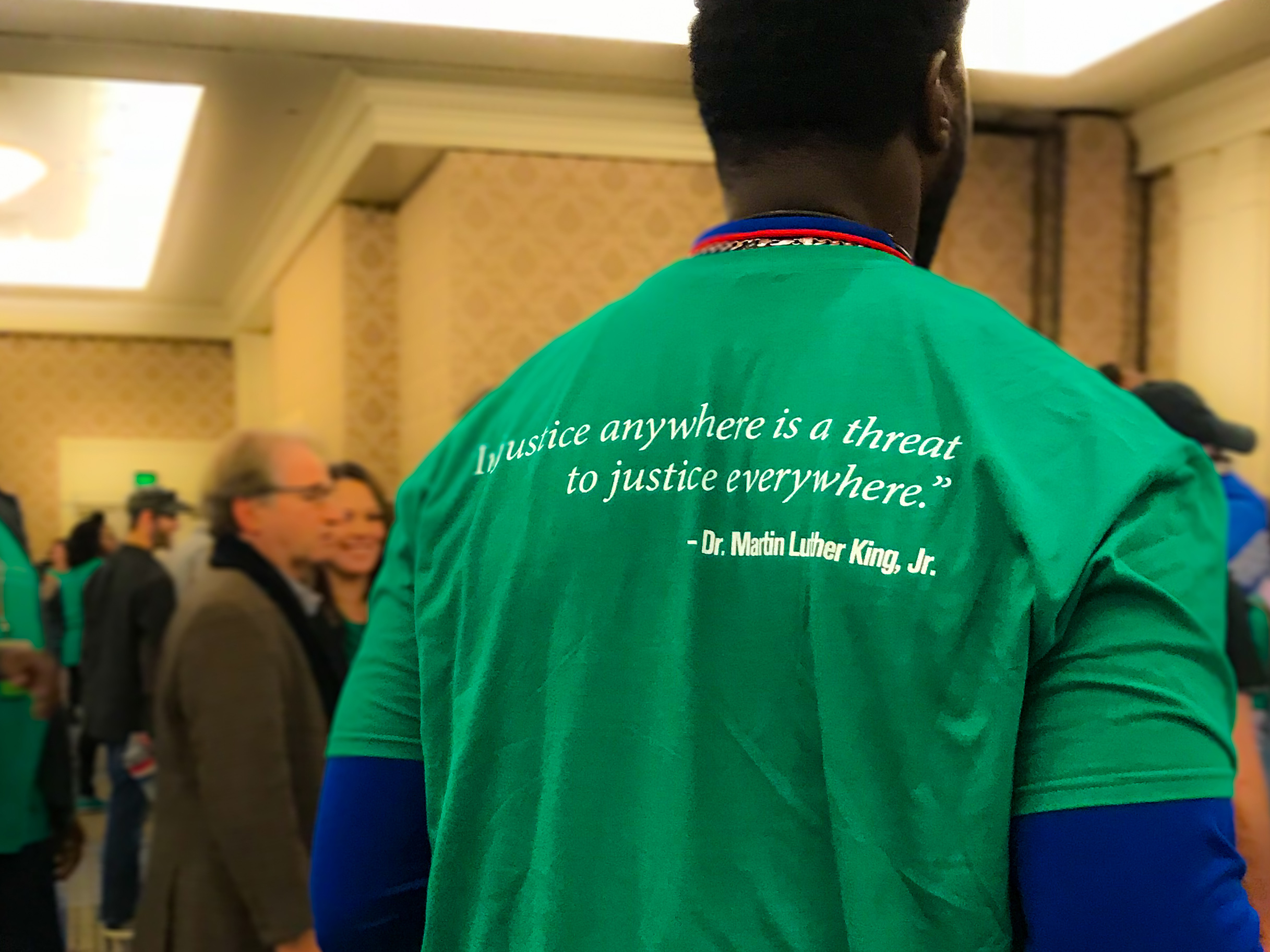

Conference T-shirt – “Injustice anywhere is a threat to Justice everywhere.” Martin Luther-King

According to the NRE, the leading causes of wrongful convictions are eye-witness misidentification, perjury or false accusations, false confessions, false or misleading forensic evidence and official misconduct.

“Race is also a huge issue,” Molaudzi adds. “The majority of exonerees I met were poor, young black men like me when I was arrested. They couldn’t afford private lawyers and were forced to rely on the State for legal assistance. It’s the same in SA.”

The choice of Memphis, the city where legendary civil rights leader Martin Luther-King was assassinated fifty years ago, as the venue for a conference themed “Race and Wrongful Convictions” was clearly not coincidental – especially at a time when mass incarceration is increasingly seen as a pressing human rights issue. With 2.4-million Americans currently behind bars and the highest prison population and incarceration rate in the world, wrongful convictions appear inevitable.

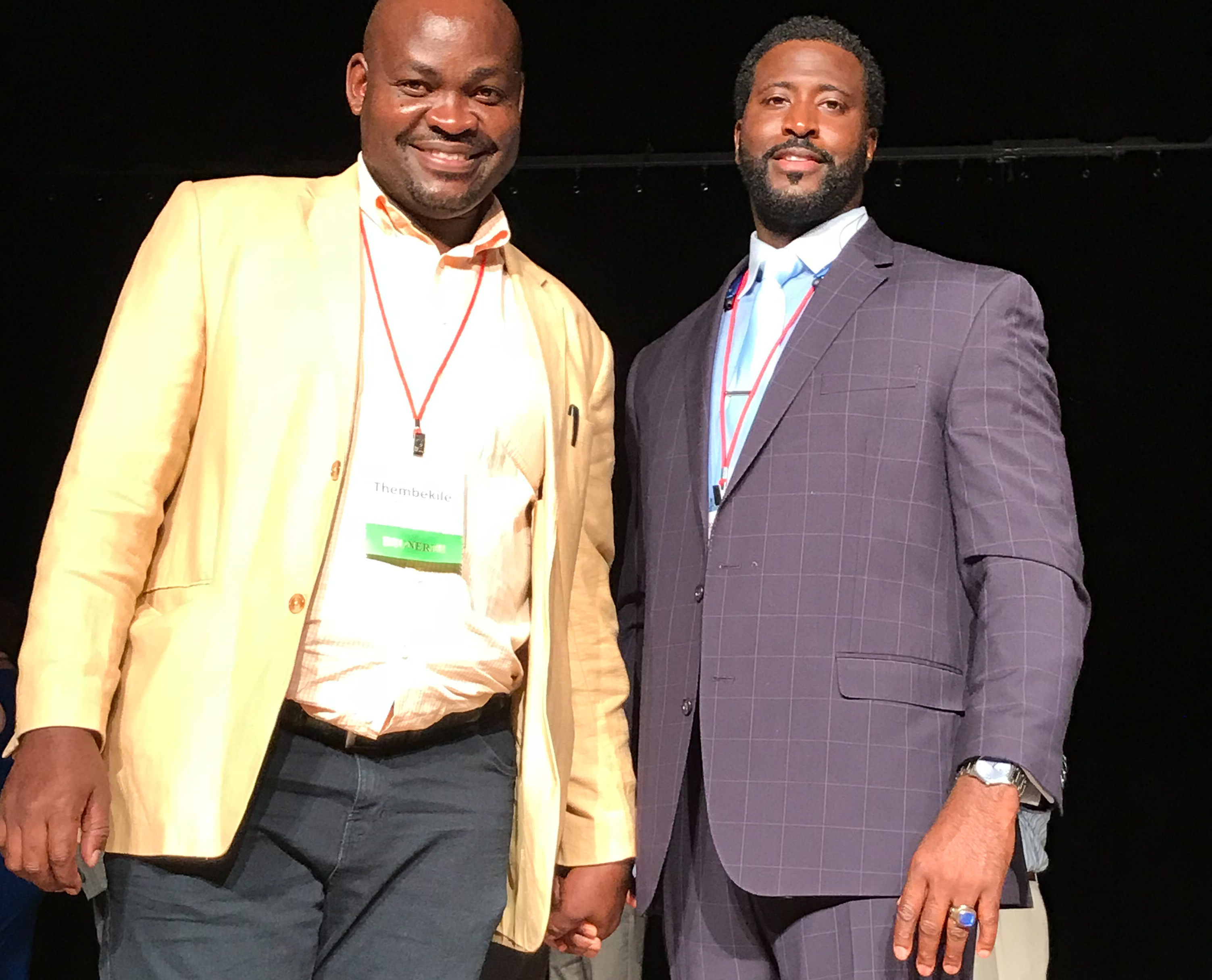

Jimmie Gardner, one exoneree with whom Molaudzi struck up an instant rapport, was a hapless victim of a particularly egregious miscarriage of justice. As a 19-year-old prospective baseball star drafted as a pitcher by the Chicago Cubs, he was charged with robbery, rape and assault and sentenced to 110 years behind bars. Though Gardner’s “victims” denied his involvement in the crime, he was found guilty as a result of an expert state witness who knowingly presented falsified forensic testimony at his trial.

It later transpired that Gardner was just one of over 140 cases in which this state serologist gave false testimony. Though the serologist was exposed as a fraud and convicted three years later, Gardner protested his own innocence for nearly 27 years before his 2016 exoneration and release.

“Jimmie’s lawyer tried to persuade him to admit to a crime he never committed but he refused,” Molaudzi explains.

“The prosecutor also tried to persuade him to admit to something he didn’t do to get a lesser sentence and he refused. People representing the state just want convictions, convictions, convictions… There was no evidence linking either of us to the crimes we were supposed to have committed.”

Thembekile with Jimmie Gardner

After a David-and-Goliath battle to prove his own innocence which he waged even during three years of solitary confinement in Kokstad’s Embongweni prison, not much phases Molaudzi now. Survival in prison, one of the Memphis exonerees observed, is dependent on acting like the famous Peabody ducks which waddled across the hotel carpets to the lobby-fountain in a twice daily ritual: “You have to appear calm on top,” he said, “and paddle furiously underneath.”

Clearly, this isn’t always possible. “Prison is not a fairy-tale,” Molaudzi notes with good reason. “Strange as it may seem, sometimes people even confess to crimes they never committed – often after they’re tortured. One of my co-accused, Sampie Khanye, whose wrongful conviction was also overturned by the Constitutional Court last year, made a false confession after being assaulted, beaten with a hose-pipe and broomstick, tortured and given electric shocks by the police. He couldn’t take it any more…”

Amanda Knox, probably the most high-profile exoneree at the conference, has also consistently claimed to have been psychologically tortured into making a false confession – after 53 hours of police interrogation, under extreme duress in a language she didn’t fully understand while studying in Italy on a gap-year. Now the best-selling author of Waiting to be Heard, Knox maintains she was threatened with 30 years in jail, hit over the head by her interrogators and falsely told she had HIV. As a result, she not only made a false confession regarding her role in the murder, but also falsely accused her boss.

The then 20-year-old American student was twice wrongfully convicted for the 2007 murder and sexual assault of her house-mate. Knox was sentenced to 26 years in prison with no physical evidence linking her to the crime and spent nearly four years in an Italian prison before being found innocent in 2011. Back in the US, she spent four more years in a protracted legal battle to re-prove her innocence after Italy’s highest court annulled her acquittal and she was found guilty again. Twice convicted and twice acquitted of the same crime, the Italian Supreme Court definitively exonerated Knox in 2015 due to “stunning errors in the investigation”.

Thembekile with Amanda Knox

For Molaudzi, attending a “Writing to Heal from Trauma” conference workshop which Knox facilitated proved both therapeutic, and painful. “It brought everything back and caused me even more pain,” he says.

“I had flashbacks and relived my trauma. Sometime I’d listen to other people’s stories and forget that I’d also been in prison, then I’d remember…”

At the culmination of the conference, Molaudzi joined a virtual army of innocence warriors calling for urgent criminal justice reform on a march through the streets of Memphis to the Lorraine Motel – now the National Civil Rights Museum – where Martin Luther King was felled by a sniper’s bullet. With the words of the civil rights icon “Injustice anywhere is a threat to justice everywhere” on every demonstrator’s back, the placard-carrying troops repeatedly hollered their demands for “Justice! Now!”

After the march – Thembekile outside the Lorraine Motel – the National Civil Rights Museum – where Martin Luther-King was assassinated fifty years ago

Standing outside the museum, Molaudzi observed how little attitudes to race, justice and equality appeared to have changed since King’s death: “The travesty of justice that happened to me is not unique. There’s still racism and prejudice in America and in SA and rich man’s justice if you haven’t got money. After all those years in prison, I didn’t see much difference or change when I was released.

“I went to Memphis hoping for healing but left realising that healing doesn’t happen overnight. It’s a process which will take a very long time. When my family visited me for all those years, they were supposed to comfort me. Instead, I had to comfort them. I learnt to hide my feelings, to have a blank face and bleed inside. I’ve learnt that forgiveness is the first step in healing and pain is part of healing. Being bitter, holding grudges and looking backwards will only destroy me. Now, I want SA to know that wrongful convictions happen. I want to organise SA exonerees, to help them forget the past, to make peace with what has happened and move forward…” DM

Molaudzi attended the Innocence Network Conference in Memphis thanks to the generosity of the UK-based Canon Collins Trust which provided him with a Sylvester Stein travel fellowship

Become an Insider

Become an Insider