Spirit Dance

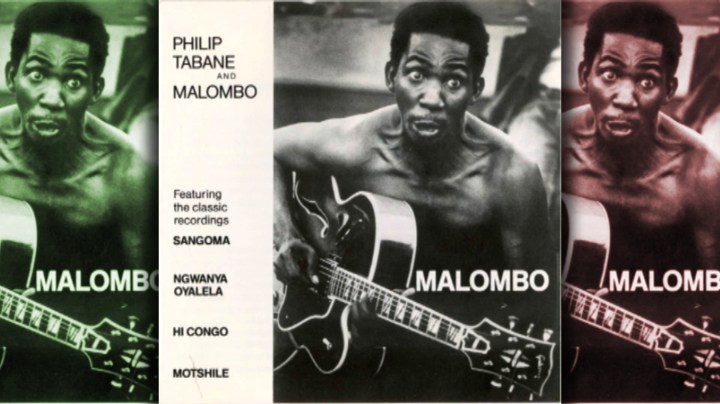

Philip Tabane (1934-2018): The ‘best guitarist in Africa’, no longer with us

The extraordinary musician, Philip Tabane, has passed away and his unique talents have been stilled. But his influences continue.

Back in 1975, still just into my first months of working in South Africa, I learned that our office (the cultural, media and information arm of the US Embassy) also functioned as the support staff of the Johannesburg Music Appreciation Society. Given the prevailing circumstances in South Africa, with few if any venues open to all in the city, we had an active “membership” of people for that society, ranging from office cleaners to the head of (black) personnel for the country’s largest construction company. Regardless of what the afternoon’s programme was, the room filled up. Very quickly.

Our prime task was to develop a varied programme for the monthly meetings. These included events such as afternoon workshop-demonstration-talks by visiting American jazz musicians such as Barney Kessel, playing at the country’s still-segregated nightclubs, but still before the cultural boycott began to take hold. Then there were our home-grown efforts such as our talk, with the recorded music, on the Kurt Weill-Maxwell Anderson musical, Lost in the Stars, that had been made of Alan Paton’s novel, Cry the Beloved Country. (It has some great music in it, even if it sounds rather more Weimar German than South African.)

But beyond any doubt the biggest hit we ever had was the conquering hero’s return performance by Philip Tabane and Gabriel Mabe Thobejane as the duo, Malombo. They had only recently returned home from an extended period of residence in America where they had been the opening act for greats such as Miles Davis and Herbie Hancock in some of New York City’s premier nightclubs and music spots. Musican Sello Galane, whose own doctorate in musicology had focused on Tabane and his music, wrote of that experience:

“Everyone who left the country at the time wanted to meet people like Davis, Freddie Hubbard and Herbie Hancock, but when he [Tabane] went to New York in 1971 they wanted to meet Tabane. ”

To be honest, I didn’t know very much about Malombo at the time, other than the information above. (In fact, I only knew a little bit about African music through the popularity of the drumming of Nigerian artist Babatunde Olatunji or the Congolese choral work, Missa Luba. While I was familiar with some South African music by stars like Miriam Makeba and Hugh Masekela, or the song, Wimoweh/The Lion Sleeps Tonight/Mbube, that was about it.) As a result, I wasn’t really ready for the tsunami of would-be audience members who, with absolutely no publicity, had learned of our Malombo performance. They flooded into our office, and then they filled our modest auditorium to well beyond the fire code limits.

An hour or so before show time, the two musicians arrived and quickly turned our office into their green room. That room quickly filled up with a haze of smoke from the holy herb and curls of smoke began to waft out into the corridor. Already wondering about what else was going to happen, I was asked for a favour. As a white guy legally allowed to buy hard tack – when the black staff could not do so by virtue of the Liquor Control Act – I was dispatched to buy a half-jack of Old Brown Sherry for the two men to assist in their warm-up routine.

By this time, the still-growing crowd was filling the staircase and the hallway, and we were well beyond the safe occupancy number for the entire office suite. No matter. I was actually more worried about whether we would have two musicians who would be too mellow to perform – and then would I do with all those people?

I should not have worried, these men were pros. Philip Tabane plugged in his favourite Gibson guitar and made some small adjustments on the electronics, while Mabe Thobejane continued to warm up the skins of his African percussion drumheads with a portable two-bar electric office heater to stretch them to just the right pitch, and the show began. Almost as soon as they began their set – Philip on guitar, a handful of pennywhistles and a flute or two, and Mabe on his drums, shakers and various rattles – I was captured. Totally.

The complex aural patterns were like nothing I had heard before. It wasn’t jazz, it certainly wasn’t pop music – African or western; it wasn’t the frenetic drumming such as that from Olatunji’s group. In fact, Philip Tabane had fastened on to something very new and fresh – and very old, simultaneously – as his musical repertoire. And he appropriated whatever else from the musical universe he thought might be necessary for the effects and textures he wanted. The result was a complex weaving of musical ideas and guitar riffs that sounded like a whole gaggle of instruments, as well as flute sounds like soaring birds, and the interweaving of the percussion as both complex commentary and rhythmic underpinning of the whole enterprise. It was hypnotic, tantric, trance-like. And then the very meaning of the name of the duo, “Malombo”, began to come clear.

In Tshivenda, “Malombo” means “spirit” with an inflection towards “exorcism and purification”. Tabane always said he gained his musical training from his mother, but his inspiration from his ancestors, the spirits. In fact, at one dinner in our house in Pretoria, back in 1991, in honour of the newly-returned-from-exile fellow musician Abdullah Ibrahim, Philip Tabane had spent most of the evening sitting quietly in a corner, communing, as he said, with the ancestors. No one would have disturbed that process, given his musical genius. He had, after all, been dubbed “best guitarist in Africa” – by none other than Rolling Stone magazine, right on its cover.

Watch: Malombo at the Market Theatre

Philip was a true son of the black township of Mamelodi, located just beyond Pretoria, and his family lineage was both Tswana and Ndebele (although some said Venda was in there too). His original performing group had been as a trio with two other hugely talented musicians, Abe Cindi and Julian Bahula. That group was hugely successful, winning numerous live music competitions, most notably the 1964 Jazz Festival at Orlando Stadium. When Cindi and Bahula left the country, in the following years, Tabane recruited various others to join with him in duos and trios, including his son, Thabang, for a time.

Renowned novelist/artist/musician and cultural commentator in both America and Africa, Zakes Mda, located Tabane on the country’s musical map, saying that he had known him “since the early sixties when he was just starting with a new band called Malombo Jazzmen with Abe Cindi and Julian Bahula. Their song Foolish Fly inspired a lot of my creativity, mostly as a flautist. In my memoirs I write about how we used to jam together in Maseru at Tom Thabane’s house (he’s now Lesotho prime minister) after Cindi and Bahula had left for the UK (as the breakaway Malombo Jazz Makers) and Tabane was then with Gabriel Thobejane. Only a few weeks ago I was in Cleveland to work with Khela Chepape Makgato and throughout that day we painted to the music of Malombo, and I introduced Foolish Fly to Khehla, himself a long time lover of Malombo, the music of the spirits.”

Eventually, Mabe Thobejane left to be one of the musicians in the group Sakhile. There, he helped bring some of Tabane’s aesthetic, but merged it with group leader Khaya Mhalangu’s more straightforward cool jazz approach. Soon enough, other great ensembles such as Bayete were also drawing from the ancestral musical ideas and traditions, even as they brought such sounds together with jazz, rock and other popular modes. (It is even possible to point to Johnny Clegg as yet another kind of explorer yet kindred spirit, in his merging of those Zulu maskandi traditions with pop music for his own spiritual journey.

But through it all, through all those years of performance, Philip Tabane remained his own best, unique muse. My wife and I once heard him performing at a small club where he had somehow fastened on to the venerable English folk tune, Country Garden, as the starting point for one of his compositions. Seemingly, just to show he had some good jazz chops too, he took that tune a very far distance from its own origins. It went so far, in fact, that his percussion colleague at the time simply ceased playing for a minute or two, just so that he could also marvel at where this musical expedition was going to end up. By the time that piece had ended, you were still wondering what magical route Tabane had just taken.

Sadly, while numerous recordings have been issued of Tabane’s Malombo performances in the group’s various incarnations, no studio recording ever seems to have transmitted the electricity and visceral excitement of hearing the music at a live performance – not even in listening or watching a DVD of a live performance. The sheer frisson of that live experience is somehow less, even if the sheer virtuosity of it all can easily be savoured on those recordings.

David Coplan, the author of the authoritative volume on South African black popular culture, In Township Tonight, and a social anthropologist by training, had also played with Tabane and Thobejane for some years in the late 1970s on percussion. When he learned Tabane had passed away, he wrote to say:

“Philip ‘Dr Malombo’ Tabane was the musical avatar of his Tswana and Ndebele ancestors; the well-spring of contemporary indigenous African music in South Africa. Off stage he was insouciant, watchful, sometimes weary of the burden of deep black consciousness that he shouldered. On stage he was a lightning storm, electrifying the atmosphere with ancient sounds that struck the earth as drums and swooped heavenward again, where flutes and voices echoed. He was an answer to the conundrum of how to sound profoundly local, an unadorned son of the soil, and African of the moment, surfing global musical waves. He was in the full South African sense of the word, ‘simple’, and we loved him for it, and for making music that gave a beat to the township street of unbroken dreams.”

Coplan has hit a big nail right on the head with his explanation of one of the key elements of Tabane’s genius. Even before black consciousness had been identified as an important South African ideological theme back in the early and mid-1970s, Tabane and Malombo were already shouldering that “burden of deep black consciousness” – putting it into musical form and giving that sustenance to their listeners and fans, even before the nation’s political language had fully caught up with it.

Kwanele Osseo, writing of Tabane’s then-upcoming performance at the Pan African Space Station music festival in 2010 in Cape Town, had also tried to pin down the uniqueness of Tabane’s musical vision. As he wrote:

“But as you flip through the pages [of the programme brochure], [Johnny] Dyani mirrors the doctor’s lifelong struggle to topple the tag of ‘mambo jazz” and chart a singular course for Malombo the group; Geoff Mphakathi, Lefifi Tladi and others trace the sociopolitical backdrop that necessitated Tabane’s resistance; and Salim Washington and Sazi Dlamini discuss ‘indigenous, alternative possibilities’ and music as a door to life, echoing Malombo’s guiding principles.”

For years, Tabane and Malombo were not performed on SABC radio. As music producer/archivist Dave Marks has written of that time:

“Not everybody in the remote record or radio controlled industries back in the ‘60s considered Malombo music cool – ‘too African…’ Too streetwise; Herd Boys, or Cow Boys busking for a living banging Buck-Hide drums, blowing Pumpkin Pipes or rusty tin whistles & spanking a wired up out-of-tune plank? Making street music on stage had no place among the swank & splendour – some would say squat & squalor – of the US Big Brass Band Township era.”

But audiences couldn’t get enough of it. At his peak of fame and popularity, he would fill university great halls with people of all races, come together to hear Tabane and company commune with the spirits and the ancestors.

Eventually, to go with international fame, in the post-apartheid years, Tabane gained establishment recognition via various awards, including an honorary doctorate from the University of Venda. But the real recognition of his music surely came most of all from the legions of fans who were captured by Tabane’s authenticity of spirit. Besides the great music, of course. DM

Become an Insider

Become an Insider