FLIXATION

How the Beatles (including George Harrison) Changed our World

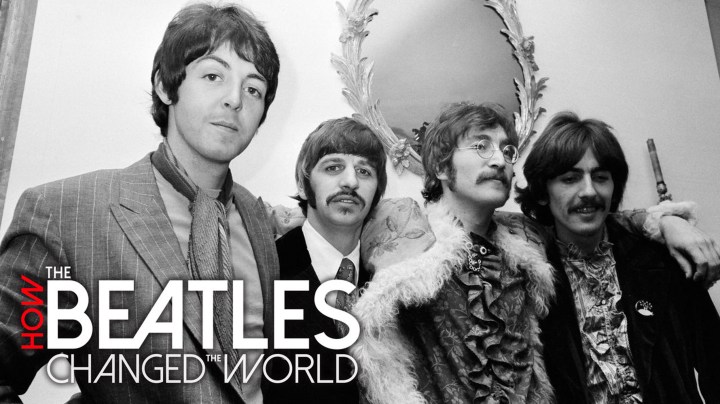

The Beatles were at the heart of the cradle in which our contemporary world was nurtured. And George Harrison was the Beatle whose output was sidelined to the benefit of his peers Paul McCartney and John Lennon. Two documentaries on Netflix offer a chance to assess their relative contributions to popular culture.

Do we thank Hitler for the dank irony that his twisted vision of a tyrannical Reich created the perfect climate for the great wave of cultural change that followed in its wake? Would the Sixties have been what they were without him? And the Twenties. A decade you would have loved to have lived through were it not for the knowledge that it was sandwiched, more or less, between the two world wars. Would the Flapper era and the Jazz Age now so closely associated with F Scott Fitzgerald have been what they were without the draconian mayhem that had been their precursor? And does this have any meaning for our current mess of a world?

The correlation between the Twenties and the Sixties fascinates me. If you’re the child of parents who fought on the side of the Allies in World War II, and knew, palpably, the effect it had on them, on their psyches, and their manners, foibles and fears, and if you’re a thinking person, all sorts of things make sense. You become, the more you think, a teenager who wants to be much unlike your parents. If your dad wore his hair short, back and sides, and took you to the barber’s every Wednesday at two o’clock even though, looking in a mirror, your hair apparently hasn’t grown a millimetre, you grow up wanting your hair to grow long and lush. If your dad wore boring trousers, a blazer and his club tie, you were going to grow up to want some colour in your shirt, no collar, and powder blue denim jeans. By the time you were a teenager, your dad might think you delinquent, an unknowable creature from another world and time. Because it was. That’s how different those two generations were in the Sixties. It’s where pop rebellion was born, right there, in 1963, to be precise. When you were just eight.

It mattered not where you were. We were in a tiny diamond town sandwiched between nothing and nowhere, desert on all sides but for the taunting river that ran through it. But the Sixties seeped itself into our consciousness through the music and the magazines. We soaked everything up, and as soon as the parents were looking the other way we’d throw ourselves right into this new cultural revolution.

Looking back, from now till then, from the older man to the little boy on the verge of adolescence, I find my mind casting further back to the kids whose parents had come out of the earlier Great War, and how the fashions alone of that time – the time of my grandparents – were so gobsmackingly different from those of the Edwardian era we now probably know best from the earlier episodes of Downton Abbey. The Flapper dresses with fringed hems that swayed this way and that to the Charlston, itself so different from the Vaudeville and drawing room recitals of only a handful of years earlier.

But my generation was given a very special, if often troubling and always complex, slice of the planet’s cultural history. We call it the Sixties, and all of it, from the fashion and the psychedelic colours to the music and the very spirit of the decade, centres on four young men from Liverpool. The Beatles.

Buried somewhere on Netflix is How The Beatles Changed the World, a riveting documentary which clearly, from first-hand accounts of those who were at the epicentre of it, sets out quite why the claim in the show’s title is true. It seems a somewhat wild claim to make – it’s easy to ask, but how do we know the decade would have turned out very differently if the Beatles had not happened? But that’s because everything that happened in their wake, and which sprang from what they did, how they made music and how they dressed and conducted themselves (itself groundbreaking for their time), has been affected by them. Before them, singers and band members when interviewed would answer ever so politely. The Beatles chirped. Seems so ordinary now, but back then it raised eyebrows and brought frowns of disapproval.

And the sounds we hear on the charts today are still massively influenced by the Beatles. Many contemporary acts openly cite them as influences. And it’s not 20 years ago today, not 30 years ago today, not even 40 years ago today. Right now it’s 55 years since the Beatles broke out of smoke-filled nightclubs and into the new world’s consciousness.

Watch:

That was 1963, the year the Sixties started, because there’s a differentiation between the decade of the Sixties and the Cultural Decade of the Sixties. The “Cultural Sixties” began in 1963 – when the Beatles became a phenomenon, after a quiet start in 1962 – and lasted until 1973, write the historians of this sort of thing. What came before was, first of all, That War. Followed by deep austerity and crimping rations. The ones your parents told you about and which had everything to do with them being careful with, and respectful of, money and possessions for the rest of their lives.

The (cultural) Fifties had begun, right there in 1950, with a man called Johnnie Ray – a white guy who played halls filled with African-Americans, and who won their respect – who released a single called Cry. Though a slow, country-tinged ballad, it contained in its riffs the beginnings of what was to become Rock ‘n’ Roll. Listen to it, and try to imagine it revved up a bit, as it might have been if it had come out five years later. By then the world of American pop music had changed forever.

It was this music of Chuck Berry and his ilk that John Lennon, Paul McCartney and George Harrison were listening to (but not so much Richard ‘Ringo’ Starkey maybe, he always just went along for the ride), as were, elsewhere, ears such as those of Mick Jagger and Keith Richards, and others in cities across the north of England.

You may think, and I’ve thought it myself: but wouldn’t the Rolling Stones have done it anyway, or The Who, or The Kinks, and many others. But that ignores how utterly different the Beatles’ sound and image were, although at least one pop historian has argued that if there had been no Beatles, Ray Davies and the Kinks may have been the focal point of the era, having as they did their own very particular sound and burgundy-clad look and how they mirrored ordinary English life in their sometimes whimsical, sometimes hard-rocking songs. But just go straight to the Beatles’ Revolver album, issued in 1966, and there’s no doubt that right there was where everything changed, where the musical change that had been coming became perfectly formed.

That was where sitar came in for the first time, mellifluously caressing at least three of the album’s songs and making every first listener drop what they were doing, grab a beer or a joint and put the disc on again. It remains a turning point in popular music and its surrounding culture. Ever since, people have differentiated between “early Beatles” and the funkier, wilder and often experimental stuff that followed.

Watch:

And within this kernel of the band’s career lies a great and sad truth: that George Harrison was unfairly pushed aside by the Big Boys in the band, Paul and John. He had masses of great songs but he kept most of them in a safe place while the group were still together, only recording and releasing them once they’d broken up and he started a solo career. He did record some of his own with the band – most profoundly, Here Comes the Sun and Something (both on Abbey Road – Lennon even allowed him to release Here Comes the Sun as a Beatles single, a privilege Harrison had never been given before that), and the inimitable While My Guitar Gently Weeps (from The Beatles, 1968) – and earlier on, songs such as I Want To Tell You and Taxman (both on Revolver), Within You Without You (Sergeant Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band), and in the very early days the very cool Don’t Bother Me, his debut as a songwriter with the band. That said, there were entire Beatles albums without a single Harrison composition on them.

Handily, there’s a highly watchable documentary on Netflix about this underrated Beatle too, George Harrison: Living in the Material World. It’s worth watching the two back to back.

Watch the trailer from this doccie:

If the Flapper era and the Charleston were born of the horrors of World War 1 and the longhair-psychedelia of the Sixties sprang from the bosom of a sour-lipped Nazi hausfrau in World War II, could the planet’s current woes – and anyone of my era can see that our times right now are particularly dire – result in a burst of lustul energy amid a new cultural revolution in which we find new fashions, new sounds, new ways of celebrating life and joy rather than wallowing in death and misery? A post-Trump, post-neocolonial, post-Zuma, post-Kim Jong-un world where more things go right and all the bastards out there get got? Probably not, and there’s a sad thing. But it took four lads from Liverpool to change so much All Those Years Ago (another Harrison song). And it falls to the creatives to use their craft as their wile, and try to make the change.

In February 2013 I made a pilgrimage to New York’s Central Park where, opposite the Dakota Building on Central Park West (the setting, incidentally, of Roman Polanski’s creepy movie Rosemary’s Baby), one word in mosaic reminds us of the world John Lennon would have liked: Imagine. And your thoughts cross the road where, in 1980, around the corner, at the entrance to the Dakota Building where torches now burn Lennon’s memory into our time, a sour-minded young man with a gun pulled the trigger on whatever music might have followed had he lived through the Eighties and Nineties and been an old man by now. Imagine that. DM

Become an Insider

Become an Insider