(All photos by Karl Ammann)

A groundswell of economists and conservationists have written reports dealing with the demand-and-supply characteristics of the trade in rhino horn. Although the picture of supply, and how this chain works, seems clear, the demand side is a lot less certain, as well as how the end-consumer drives it.

My research with South African filmmaker Phil Hattingh for The Hanoi Connection, our feature-length 2018 documentary on the driving forces behind the rhino massacre, kicked off about six years ago by scouting for products in traditional Chinese/ Vietnamese medicine shops in Vietnam. To secure the acceptance we needed, we established ourselves as customers over several trips to Hanoi, the capital, by buying samples of powdered rhino horn or small pieces of horn cut from bigger chunks.

When a chopped piece flew into the street while a dealer was sawing so-called rhino horn with heavy equipment on her shop pavement, it became clear that customers were probably being deceived by all kinds of bogus products purporting to be rhino material. After all, the real-deal product would not be treated so carelessly — nor sold to us at the price we paid for the flying fragment.

A traditional Chinese medicine dealer in Hanoi, Vietnam, hacks

off rhino-horn portions on her shop pavement.

Outside Hanoi, we filmed a production facility for fake horns and faux hunting trophies, which included adapted water-buffalo horns. Then we documented thousands of fake horns for sale at a specialised market for wildlife artefacts in Guangzhou, China.

Approaching several wildlife-oriented genetics laboratories in 2014 with samples from these initial trips turned into something of a challenge: most agreed to analyse them for us — but they were concerned about publishing the data without the necessary import and export permits.

The year before, the parties to the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species (CITES) had decided in Bangkok that seized samples of rhino horn or horn products should be handed directly to designated laboratories. It had become clear that there was little, if any, secure storage for rhino horn in supply-and-consumer destinations. This seemed especially true for Vietnamese officials, who seemed to think that they had good reason to keep the exchange of samples for enforcement purposes to a minimum. In one incident, the officials supposedly tried transporting samples to South Africa. These were then “stolen” en route.

The central issue with our approach to laboratories, of course, was that we as filmmakers and investigators were not party to CITES. As such, trying to source export and import documents, and filling them in accurately, would have been a complete waste of time — we could not even positively identify the products until the DNA results were in.

Testing fake tiger bones for our 2016 documentary The Tiger Mafia helped place things in some perspective: a Swiss-based university lab got a legal opinion stating that it was not infringing on any law if it was doing analysis to determine a particular species; or, indeed, if any such samples turned out to be from CITES-listed species.

We were aware that we faced another challenge here: showing our hand too early through releasing our samples to laboratories, or the corresponding results, might have jeopardised future investigations.

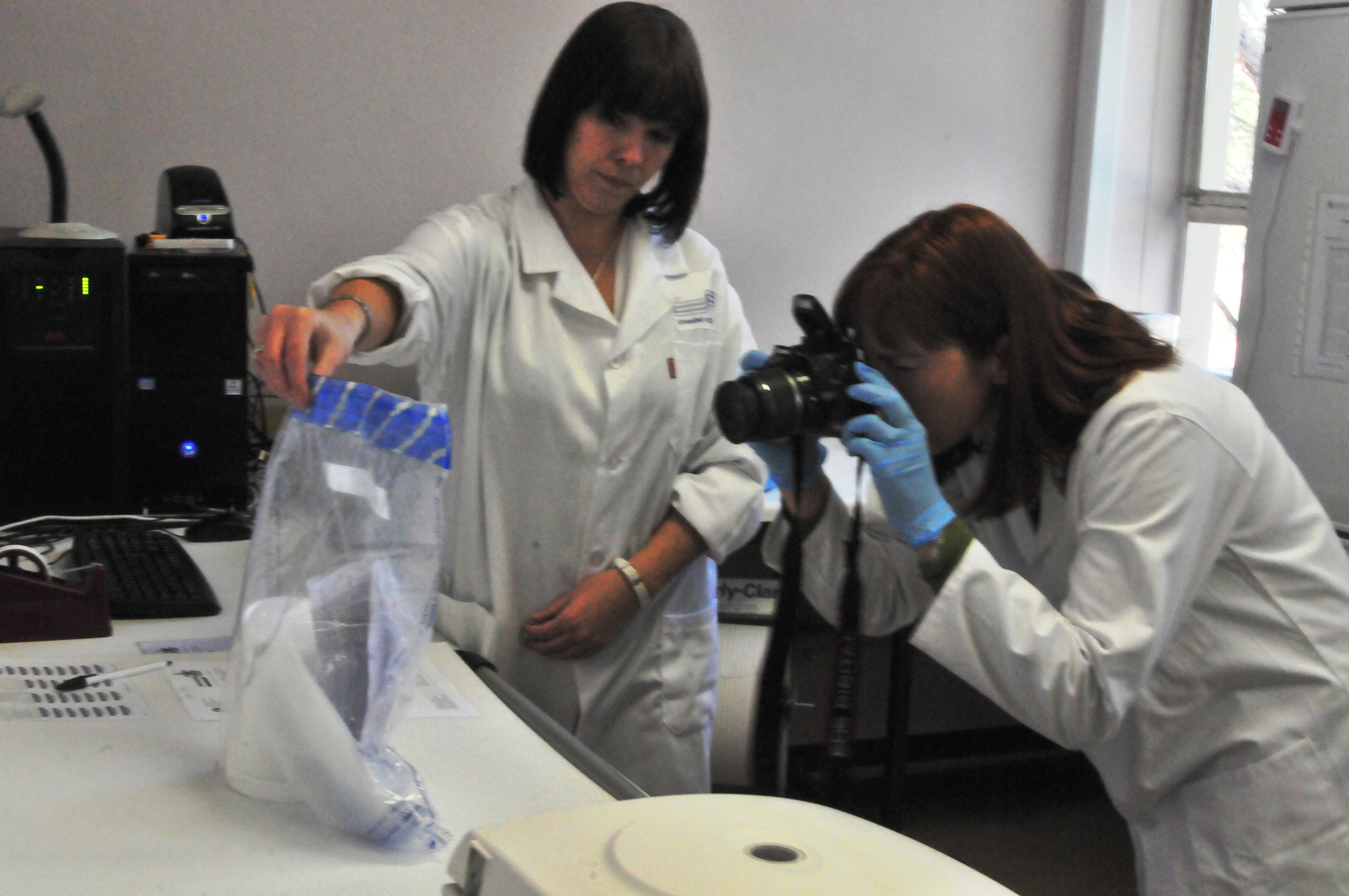

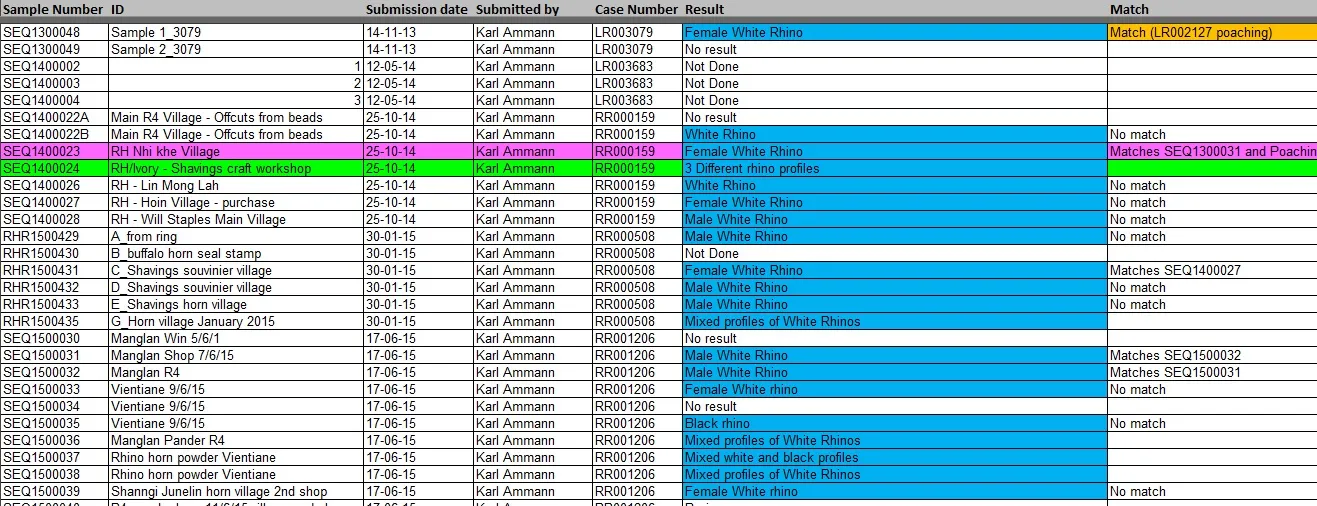

For this stage of our demand-side investigations, the Veterinary Genetics Laboratory at the University of Pretoria would prevail as a testing solution. Set up and developed by Dr Cindy Harper and her team as a tool to aid enforcement, the laboratory’s Rhino DNA Indexing System (RhODIS) has a mission enshrined in the South African Biodiversity Act. First used in a rhino-poaching case in 2010, RhODIS analyses samples of as many dead and live rhinos as possible. DNA is continually collected from southern and East African range states, and tested. The system’s database today includes DNA profiles of more than 20,000 rhinos.

The DNA testing lab in Pretoria, which hosts the RhODIS database.

Our samples were delivered to the lab by various parties travelling to South Africa. If any CITES permitting issues were to arise, we could legitimately argue that we were not sure what exactly we had acquired.

A wide range of horns are imported from various

parts of the globe and many are worked into ‘rhino-horn’ products.

A wide range of horns are imported from various

parts of the globe and many are worked into ‘rhino-horn’ products. (02)

As it turned out, the RhODIS test results showed that roughly 90% of the fragment and powder samples from traditional Chinese medicine stores did not even remotely involve rhino horn. Instead, what we had was Saiga antelope (a critically endangered antelope remaining in southeast Europe and central Asia), kudu, sheep and a whole lot of water-buffalo horn.

Next, we targeted jewellery and artefact stores in China, Myanmar, Laos and Vietnam’s upmarket tourist areas — these flogged a staggering range of wildlife products — and discovered that most of the real rhino horns marketed in these demand countries now seemed to end up as luxury items.

Dealers would tell us that buyers blowing the equivalent of hundreds of thousands of US dollars for raw horn would often bring their own experts to check the quality of the product. Trying to cheat buyers at that level would certainly be a risky business.

Some stores also sold medicinal shavings — byproducts automatically created when grinding real rhino horn into top-end offerings such as bangles, libation cubps and signature seals.

Based on our personal observations and interviews, buyers in these mostly Chinese-owned stores were pretty much 100% Chinese visitors — given these outlets’ geographic location in countries neighbouring China.

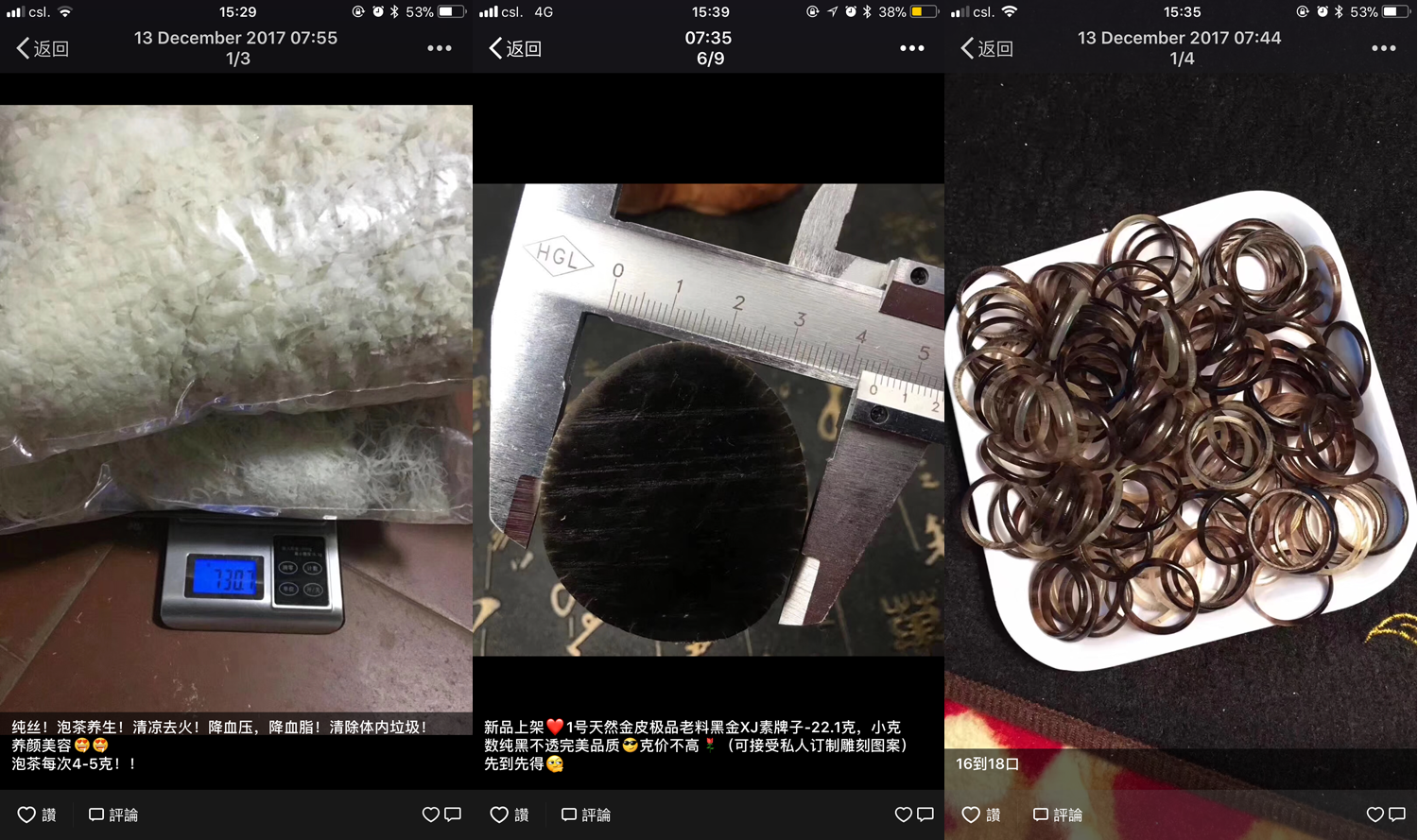

Many would acquire a slew of pieces for their friends and relatives back home, offering these products via Chinese messaging app WeChat (their WhatsApp equivalent), an informal system fast-tracked by free instore wi-fi connections: in some cases caught on our hidden cameras.

Chinese social-media applications, such as WeChat,

are used to send and receive instructions instore.

Our assessment was that trading in fake fragments of a few grams each was particularly alluring to swindlers — by attracting a less powerful, less affluent and less knowledgeable clientele.

Traders of authentic rhino-horn products also seemed to create ever more downmarket products to get this less discriminating segment to come on board.

For raw horn, recent reports indicate a dramatic drop in the price per kilo across the whole of Southeast Asia. Dealers were, in 2017, largely quoting $20,000-$28,000 per kilo, compared with a price of $60,000 per kilo some four years earlier. There has been no explicit answer for this trend, but some dealers indicated that either speculators might have dropped out of the scene, or additional supply entered the market.

However, at the retail level, prices have not really changed; manufactured products are generally quoted at about $80-$160 per gram for a ring, karma bracelet, medallion, comb, drinking cup and so on.

Compared with ivory at $2-$4 per gram, the asking price for rhino-horn shavings from the workshop floor is $10-$20 per gram — some eight times less than the per-gram price for finished luxury horn items.

Samples of rhino horn … or are they? One piece here is real, the other is fake.

Clearly, the traditional Chinese medicine component is no longer the dominant market force: the shavings and powder have become mere byproducts, leading us to the conclusion that the demand for rhino horn has moved from “health” to flaunting wealth.

These decorative pieces can be bought via Chinese social media applications.

Status — in particular, the social prominence associated with expensive, verboten goods — now drives the demand, while fakes continue to be sold even at this level in parts of Southeast Asia.

The same smoke and mirrors seem true for lion-bone exports from South Africa to Laos. These bones do not stay in Laos. Filming local dealers, our hidden cameras documented that they were instead trafficked into China and Vietnam. Here they are sold as tiger bones, resulting in a litany of CITES infractions along the way.

Labelled “rhino-horn shavings” in a Laos shop

catering to Chinese visitors.

While our medicinal samples came from traditional Chinese medicine stores selling fake products, our samples from luxury jewellery and artefact stores have proved quite the opposite: 90% of the samples from these sources have turned out to be the real thing.

Collected over the past three years, these samples have yielded some 40 real, individual rhino DNA profiles. Mostly, RhODIS technicians found white rhino DNA, but also some black.

The most intriguing finding revealed that 90% of samples did not even match any of the RhODIS database profiles for poached rhinos.

A sample from the RhoDIS Database based at Onderstepoort Veterinary Lab in Pretoria.

This raised some interesting new questions: where did these other supplies originate?

South Africa has a control system that registers all live rhino in private hands and potentially highlights any missing individuals. Indications are that this system is far from watertight and unscrupulous owners can find ways of selling horn “out the back door”, without fear of repercussions. Local private rhino owners told us that they regularly received calls from potential customers asking to buy horn. There have been no cases of private rhino owners prosecuted for “missing” rhinos, or horns “missing” from rhinos living on their properties.

Images sent to our contacts in China, demonstrating how the trade is moving online.

Since there is only a scattering of local consumers in South Africa, is the present move to legalise the domestic trade simply a way of formalising a thriving home market whose products already end up being traded globally — as our sampling seems to indicate — currently in contravention of CITES rules?

In 2016, a Zambian government store was broken into. Diverse horns were stolen, turning this source into another potential supply line not covered by the RhODIS database. So far most range-country governments, such as the Zambian administration, have not asked for their stocks to be included. If any organisation could legitimately pressurise them into doing so, it would have to be the CITES Secretariat, headquartered in Geneva.

Using special evidence bags and containers to label sample products, as stipulated by Interpol.

Murdered conservation investigator Esmond Bradley Martin had published a report in 1992 in Pachyderm magazine stating that the Chinese government had at the time held close to 10 tons of rhino horn in stock. One pharmaceutical company alone had some four tons in its possession.

Clearly, none of it is in the RhODIS database. Will the CITES Secretariat ask to verify these stocks?

Might this supply have entered the market when the price for raw horn hit some $60,000 per kilo a few years ago?

In huge areas such as Kruger National Park, some rhinos might be poached but never found.

Plus, there have been rumours of samples from rhinos poached in the park sometimes taking three years to reach the lab in Pretoria. Were we bringing back end-product specimens from Southeast Asia, while the evidence bags from the poaching scene were still in some store at the park headquarters?

There are also indications that the lab seems to be sitting on a considerable backlog of samples requiring analysis.

All these unaccounted sources indicate that the demand and supply might be much bigger than the recorded 1,000-1,200 rhinos officially poached in southern Africa each year, and that there might be other sources of supply.

During the 17th CITES Conference of the Parties in Johannesburg, in September 2016, we discussed with several country representatives the value of our research, as well as the restrictions and potential impact on enforcement.

One of the key South African enforcement authorities decided that a formula should be found to get rhino-horn samples back to the lab in Pretoria under controlled conditions: we would be given Interpol contacts in Southeast Asia to whom we could hand the samples and who would get them to Pretoria. Although we were still concerned about being challenged on circumventing CITES during this, our latest collection trip, at least we knew the Interpol deal was meant to create a more clear-cut scenario for the labs doing the work.

Travelling to Southeast Asia with Phil Hattingh as the cameraman, we followed the stipulated collection procedure — using special evidence bags and containers — and established the chain of custody by also photographing shop exteriors.

The sales transactions were filmed with a hidden camera.

By the time of our departure back to South Africa, Interpol had still not given us any contacts to whom we could give the samples.

On that particular trip, I then travelled back with some of the samples via Zurich.

At the airport security check, I was pulled aside. Various items of my carry-on luggage were swabbed to check for drug traces.

Of course, there was no problem. Rhino horn is neither cocaine nor heroin.

However, I have little doubt that similar tests could be developed for not only rhino horn, but also ivory and tiger bones and other high-profile wildlife products.

This well-travelled horn has crossed multiple borders without

being detected once.

South African and Chinese authorities could do regular tests of hand baggage on flights arriving from supply countries at demand destinations. Kenya deploys sniffer dogs walking on the baggage carousel, but I have never seen that happen anywhere in Southeast Asia.

I have also travelled, crossing over half-a-dozen borders, with very well-manufactured, fake rhino horns for use in presentations, fully aware that they would show up on X-ray machine displays. In fact, I looked forward to being challenged. I even had the invoice proving the origins of the fake products: from Bone Clones, a US-based company.

A horn that fits nicely in the side-pocket of a travel bag.

Not on a single occasion — at Zurich, Nairobi, New York or Johannesburg — did anybody ask me to take out those horns.

I hope some of this evidence, also earmarked for upcoming publication by DNA experts in a peer-reviewed journal, might help economists and conservationists reassess their position on the overall demand-and-supply characteristics of rhino horn.

However, will the enforcement authorities of demand as well as supply countries, many with serious governance and corruption problems, be interested in using any of the relevant results in the context of planning enforcement measures? Or would they rather not know?

If some countries are exposed for having bigger compliance problems than what might have been imagined, would the CITES Secretariat / Standing Committee finally recommend these parties for the suspension from all commercial and non-commercial trade — a key enforcement tool hardly ever used by the CITES decision-makers?

Since the CITES trade ban of rhino horn in 1976, it is estimated that more than 100,000 rhino have been lost to poaching. The domestic trade ban by China in 1993 has not made a difference either. Maybe it is time for the CITES policymakers to dig deeper into their enforcement toolbox.

The South African Environmental Ministry at CITES CoP16

in Bangkok, Thailand, 2013.

South African Environmental Minister Edna Molewa announced, at Bangkok in 2013, that the country would now look into legalising the trade in rhino horn … based on “having tried everything else”. DM

Become an Insider

Become an Insider