James Comey’s ‘A Higher Loyalty’

Is the price of an ethical career in government simply too high?

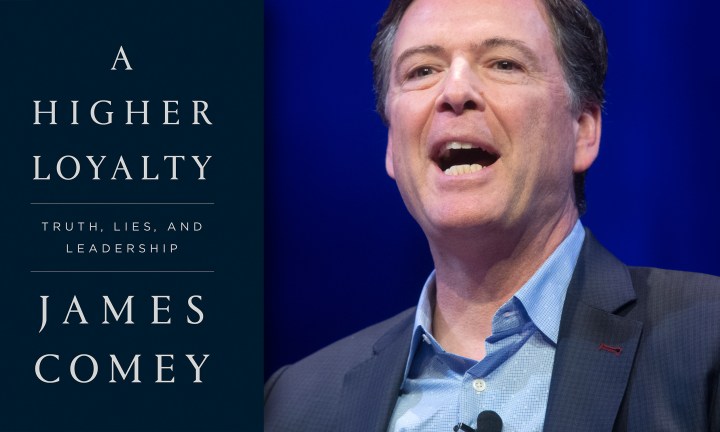

James Comey and his memoir are a lesson in ethics. The book has already had a remarkable run at the sales till, on the internet and on electronic talk shows everywhere. What is it about, really?

Half a century ago, like many university students studying political science and philosophy, James Comey discovered the writing of theologian Reinhold Niebuhr in a university course on twentieth century political ideology. Most especially, his 1944 volume, The Children of Light and the Children of Darkness, was a revelation regarding the connections between religious thought and argument on the one hand, and practical political behaviour and thinking on the other. Niebuhr had drawn his arresting title image from a line in the New Testament, “A Letter to the Thessalonians 5:5”, but he had made it his own for an audience living in the dangerous time of World War II.

Here was an author and theologian who had laboured hard to figure out how to transmute a profoundly religious idea – the deep division between good and evil that religions stress – into everyday political terms – and then answer the obvious question: “Okay, so what are you going to do about it?” And in that way, his goal was to provide real guidance for carrying that understanding into real life, rather than just as easy answers in Sunday school terms.

Added on to that first insight were the ideas that good was more than the usual liberal ideas of tolerance, and that – sometimes, in rare cases, maybe – evil was so repellent that there needed to be a temporary pause in adherence to the sixth commandment, “Thou shall not kill.” The former was a clear call to his readers that some principles are more fundamental than the tolerant “live and let live” of Western liberal democracy, while the latter was an explanation, justification, and even an injunction for Christians (and others) to oppose Nazi tyranny with every means possible until such evil was extirpated.

Of course, it did not take long for this imperative from Niebuhr to be translated by some into a full-throated opposition to the Soviet threat as well, post-World War II. In that sense, this served as the religious component and accompaniment to the American ideological response to the USSR, as well as a near-religious justification for containment and the cold war and the costs and burdens such opposition necessarily implied. (And to be sure, this dichotomy might also open the door to a kind of Manichean absoluteness towards one’s enemies, although Niebuhr obviously remained opposed to the dehumanisation of those enemies such that their mass extermination might be countenanced as well.)

It is important to realise that Niebuhr’s impact on principled opposition in the here and now (rather than just in the kingdom of God or the landscape of the soul) was also a major impact – merged together with the nonviolent resistance of Henry David Thoreau and Mahatma Gandhi to political evils – on Martin Luther King Jr’s philosophy of the urgency of the need to oppose the relentless racial segregation of mid-century America. Ultimately, Niebuhr’s impact was so big that pretty much any theologian or political philosopher in America needed to come to terms with Niebuhr’s ideas – and work them into their own respective views.

It comes as a real surprise to learn, however, that Comey – the FBI director fired by US President Donald Trump for his reluctance to shut down the FBI’s on-going investigation of the Trump presidential campaign’s connections with Russia via their meetings with Trump’s eventual pick for national security advisor, General Michael Flynn – is also an acolyte of Reinhold Niebuhr’s ideas. In his new memoir, A Higher Loyalty, Niebuhr comes up right at the very beginning where Comey, discussing his intellectual influences, wrote that while at university, after having added religion as a second major, sharing his attention with chemistry,

“The religion department introduced me to the philosopher and theologian Reinhold Niebuhr, whose work resonated with me deeply. Niebuhr saw the evil in the world, understood that human limitations make it impossible for any of us to really love another as ourselves, but still painted a compelling picture of our obligation to try to seek justice in a flawed world. He never heard country music artist Billy Currington sing, ‘God is great, beer is good, and people are crazy,’ but he would have appreciated the lyric and, although it wouldn’t make the song a hit, he probably would have added, ‘And you still must try to achieve a measure of justice in our imperfect world.’ And justice, Niebuhr believed, could be best sought through the instruments of government power. Slowly it dawned on me that I wasn’t going to be a doctor after all. Lawyers participate much more directly in the search for justice. That route, I thought, might be the best way to make a difference.”

This insight is actually a key element of Comey’s memoir – his continuing wrestling with the grubbier realities of politics in order to fulfil his belief in the more abstract virtues of justice and truth. As The Economist, in a column on Comey’s book, describing the collision between Comey’s views on justice and his actual behaviour, said of him, “Mr Comey’s error was to think his good intentions, chiefly his concern for the FBI’s independence, justified his overstepping the boundaries of institutional propriety. His main excuse, that the bureau was fated to play a role in the 2016 election anyway – it was investigating both presidential candidates, for goodness sake – emphasises his difficulty…. Mr Comey, who kept on his desk as a reminder of the FBI’s need for ‘oversight and restraint’ a request by J. Edgar Hoover to wiretap Martin Luther King, had no excuse not to know that [his two public utterances regarding investigations of Hillary Clinton’s State Department-related emails would likely alter the electoral balance in 2016]. His reputation will always suffer for his horrendous error, however many thousands of books he is about to sell.”

This book – and Comey himself through a massive media and public appearance campaign – has received enormous coverage, and the book had already topped 800,000 copies worth of sales before its actual release earlier in April. Through it all, however, the focus of this public discussion has been Comey’s run-ins with Donald Trump, his ruminations on Trump’s motives, and Comey’s eventual firing as a result of his unwillingness to pledge undying loyalty to Trump and kill the investigation into Flynn. But that sequence of events is actually only the final quarter of Comey’s book.

In his volume, Comey can be a compelling writer. His style is crisp and clear, similar to the style he must have employed when he composed his detailed memoranda following his meetings with Trump. This writing, though, is much more than the “just the facts, ma’am” approach made a by-word by fictional detective Joe Friday in the TV perennial, Dragnet. Comey is a keen observer of the small details that help make up a comprehensible and cogent portrait of a person, or as a picture of a sometimes-confusing sequence of events.

Interestingly, this book seems to be three different segments stitched together. Good stitching, but still, there are three distinctly different narratives. The first is a bildungsroman of Comey’s coming of age as a child, a teenager, a university student, and then on into his initial career in crime busting, with a special focus on the Cosa Nostra, the mob or mafia.

Along the way, once he has moved into a senior position in the department of justice during the George W Bush administration, he encounters the challenges and temptations of dealing with Vice President Dick Cheney’s near-monomaniacal focus on terrorism and extreme interrogation, and a near-comic episode in which he and a gaggle of G-men are in a standoff with a clutch of White House aides at the bedside of the nearly comatose attorney general, John Ashcroft, over the signing of a document by Ashcroft that would have given the department of justice’s blessing for such interrogations.

Like so much else in Comey’s career, this moment became a lesson in the varieties of executive vanity and dreadful behaviour at serious variance with justice and the rule of law. And all of this takes place years before Comey has even encountered Donald Trump, Hillary Clinton, and the investigations by the FBI of campaigns and emails in 2016, that comes about after he was appointed director of the FBI by Barack Obama.

Concurrently, though, there is also the James Comey who draws the larger moral lessons from all of his exertions. Accordingly, in the tradition of philosophical writers like Montaigne, he writes a pretty good meditative essay on the nature of fairness, justice and goodness in public office – and dealing with the very real temptations of power. This part could well have stood as a separate essay – and probably good as required reading – for would-be government officials and elected representatives.

Only in the last hundred-plus pages of this book do we even get to the story that has dominated Comey’s public life, post-firing as FBI director, and all the details that have been revealed via his interviews on news channels and in the myriad articles and columns written about this book and his experiences. Here he tries to explain how he felt caught between his competing loyalties to upholding the fairness of the political process, the need to keep the FBI out of politics (especially given its less than savoury history under J Edgar Hoover and others), together with the concurrent need to investigate potential crimes wherever that takes them, without fear or favour, as we like to say in South Africa.

In the end, of course, Comey is caught in an inescapable net by his expectation that Hillary Clinton would win the 2016 election, and thus that the FBI’s failure to follow up on accusations about about her use of a private email server for work-related documents would have – once the details inevitably came to light – led the FBI to being charged with covering up her alleged crimes in her favour. That, in turn, Comey has argued would have fatally undermined her legitimacy as the president once she was elected.

His rationale for failing to reveal the ongoing FBI investigation into Trump’s own misdeeds is less clear, however, save that it was not the candidate himself who was under investigation directly. That, of course, is the case, save for that infamous dossier alleging Trump’s shenanigans, or worse, in Moscow – with prostitutes and that “yellow rain” storm.

The result of all this pulling and tugging within Comey’s soul was to put Clinton into a kind of political purgatory from which there was no escape. Or, as The Economist explained, in discussing Comey’s firing and subsequent charges, “Mr Comey, in short, has played an upstanding, at times heroic, part in Trump’s America. Yet, given his lead role in bringing it into being, his book is most useful as a guide to how an ethical leader screwed up.” And, to be sure, too, this memoir stands as testament to how easy it is to make such mistakes, despite, or even precisely because of, one’s intentions not to make such missteps.

Or, as Masha Gessen puts it slightly differently in her review in The New Yorker, “The true subject of ‘A Higher Loyalty’ is the goodness of James Comey. The premise is that a man whose value is truth is superior to a man whose value is loyalty, and Comey’s understanding of ‘truth’ is as basic as Trump’s understanding of ‘loyalty’: he believes that there is such a thing as “all the truth” that exists outside of history, context, and judgment. [As such, throughout Comey’s life] Dishonest men who value loyalty bracket the book.” And not for the good, it appears.

While the specifics of Comey’s life and career experiences, and even his career-ending run-in with the whirlwind that is Trump may not be read much in the decades to come, the lessons he describes in fulfilling the needs of ethical behaviour – as well as Comey’s self-evaluation of his own mistakes – seem almost certain to find their way into syllabi in universities on the nature of justice, on issues in ethics, good government, and the important limits that must be placed on government officials – any officials. DM

Become an Insider

Become an Insider