Maverick Life

Books: An erased history unearthed about two albino brothers kidnapped into the circus

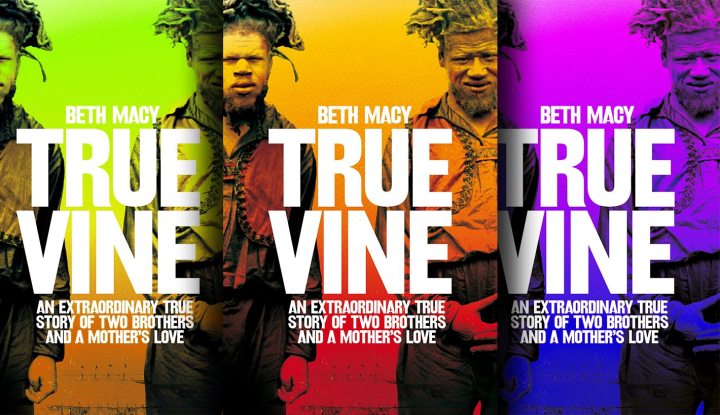

Truevine: An Extraordinary True Story of Two Brothers and a Mother’s Love was released in paperback last month by Pan Macmillan. The book tells the story of George and Willie Muse, African-American brothers born in the United States with albinism at the turn of the 20th Century, at the height of segregation laws and racial violence. Shortly due to visit South Africa, journalist and author BETH MACY describes how it took her 25 years to piece together the family's story that had never been told in public.

The Muse brothers were kidnapped as children and forced to work in circus sideshows for many years without pay. The hero of the book is their mother, Harriett Muse, who risked her life to get them back — and spent her final decades seeking justice for her family. The book is in development to become a movie, with Leonardo DiCaprio starring as the brothers’ kidnapper.

There’s a list of basic things I don’t know about George and Willie Muse, the subjects of my non-fiction book (just released in paperback). I can’t pinpoint their birth dates. I don’t know the precise location of the Virginia tobacco farm where the brothers laboured more than a century ago before a bounty hunter appeared and swept them into a world of travelling circus sideshows.

Unschooled, the albino African-American brothers never learned to read or write. Census takers didn’t accurately record their family’s names or ages, misspelling and misstating the facts of their being more often than not, and their enslaved ancestors were nameless too. American reporters — the white males, mostly, who chronicled their performances in the early 1900s — never bothered to record their views, except mockingly, as a joke.

So it took me 25 years not just to unearth the family’s story but also to understand the machinations that erased it

Early on in my research, the historian Jane Nicholas counselled me to keep digging, piecing the evidence together with equal parts documentation, empathy and context. If we only wrote the histories of the people who left detailed records behind, she said, we would only know the stories of privileged people.

She urged me to pay special attention to incontrovertible photographic evidence, the souvenir “pitch cards” the showmen sold to pad their incomes.

In the earliest known photo, circa 1914 or 1915, George and Willie are young adolescents standing stick straight in ill-fitting suits, and they look scared, probably because their manager has lied and ordered them to “quit crying — your mama is dead,” as they later recalled.

I was initially hesitant to write this book, worried about the holes in the timeline and the family’s deep-rooted mistrust of the media, including me. I didn’t yet understand my own privilege as a white reporter who knows most of my own sprawling, recorded family tree.

I couldn’t fully fathom the humiliations of a half-century of exploitation and the parallel indignities of segregation faced by their relatives back home. I didn’t know what I didn’t know.

Writing Truevine would become a reckoning for my cluelessness, a payback for the slow dawning of just how little black lives mattered to my reporting forerunners, and how that not mattering robbed millions of African Americans of their history.

When one culture fails to grasp another’s pain because the undertow of history has conveniently killed that group’s stories, the vicious cycle persists.

The showmen dressed the brothers in outlandish costumes and gave them crazy stage names. They were, alternately, “Barnum’s Monkey Men,” “The

And while the Muse brothers became world-famous sideshow stars, travelling from London to Laredo, the account of their trafficking was never told from their family’s point of view.

I found clues, though, tucked away behind

There were the cautionary words of most African Americans over the age of 60 in our region who remember their worried parents telling them to stick together when they left home as kids: “Be careful — or

And there was my own bumbling naivete to recover from, after I waltzed into a tiny soul-food restaurant in the early 1990s, young and clueless.

“It’s the best story in town,” a newspaper photographer had told me, pointing me to The Goody Shop shortly after I landed here to write features stories for The Roanoke Times. “But no one has been able to get it.”

The youngest brother, Willie Muse, was still alive, a blind centenarian who was lovingly being cared for by his great-niece, Nancy Saunders, the Goody Shop matriarch. The first time I asked to interview her great-uncle, Nancy made it clear that Willie was not now, nor would he ever be, available for comment.

I didn’t know that her first memory had been of people, black and white, banging on her family’s front door, demanding to see the “savages,” demanding to see the “men who eat raw meat!”

I didn’t understand that my own newspaper had made fun of the family when their mother, Harriett Muse, located her long-gone sons performing under a sideshow tent in 1927, then filed a lawsuit against The Greatest Show on Earth for back wages.

Or that The New York Times blithely noted the family reunion after an absence of “10 or so years,” explaining that they returned to Ringling Brothers and Barnum & Bailey in 1928, having finally “received the permission of their parents,” without noting the years of servitude that proceeded it.

Or that The New Yorker cruelly dismissed the brothers’ decision to return to the circus by claiming they were motivated by food: “The fried chicken had soon given out at Roanoke. Their relatives and friends had at first looked on them as heroes and

The relatives and friends I came to know

And they were proud, noting the irony of a pair of African Americans getting to travel the world and experiencing things that took their own families decades to enjoy. “They were the first black folks I ever knew to ride an

Photo: The photo is courtesy of The John and Mable Ringling Museum of Art Tibbals Collection. Taken in the mid-1910s, this is the earliest known photograph of George, left, and Willie Muse as albino sideshow exhibits

I wondered whether the brothers were better off, even in

I interviewed a 98-year-old woman who sharecropped for a white farmer in Truevine, Va, for six decades and who still remembers, like it was last week, what it felt like to have your lunch shoved at you through a kitchen window “because the rule was, ‘No niggers in the house’”.

Most interviewees were reluctant to open up, prompting follow-up visits and phone calls and repeatedly asking me, “Are you sure you want the truth?” Too many people, black and white, refuse to understand the harsh realities of Jim Crow, one man, 94 and bed-bound, told me. “Young people, they think we’re lying. . . . But ain’t nobody making any of it up!”

I’d been sitting at his bedside for going on two hours. He’d ended the interview twice already, saying he was tired, then kept telling stories when I stood up to go.

Reginald Shareef, a social scientist and Muse family friend, spent years advising me to be patient, to build trust in baby steps. “What African-Americans really want is for people to understand that we really have survived something — emotionally, physically and spiritually — that would’ve killed most people,” he said.

It took decades not only to earn people’s trust but also to figure out what truths prompted those holes in the family timeline, from family secrets to racist treatment by the courts, the circus industry, and the press.

It took me that long to comprehend how miraculous it was when Harriett Muse not only found her missing sons but fought for restitution, in a decades-long battle against a system that favoured the educated, moneyed whites who controlled her sons’ movements — and cleverly subverting that system at almost every turn.

Not long ago, I made the mistake of complaining to one of Nancy’s relatives about the challenges of bringing an erased history into focus.

“If she thinks it’s hard for her to write this story, just think how hard it was for Uncle Willie and Uncle Georgie to live it! She better

By then, I was ready for the truth, in a

Beth Macy is a Virginia-based journalist and the author of the critically acclaimed and New York Times-bestselling Truevine and Factory Man, both of which are in development to become films. Her forthcoming book, Dopesick: Dealers, Doctors, and the Drug Company That Addicted America about the opioid crisis, will be published by Little, Brown & Company on 7 August 2018. Truevine (by Pan Macmillan) is available in South Africa.

Become an Insider

Become an Insider