South Africa

Op-Ed: Contestations in the Ramaphosa era – what is an emancipatory route?

The Cyril Ramaphosa Presidency has been marked by ambiguities, sometimes evoking enthusiasm, sometimes disappointment. Blockages are encountered by government in removing the legacies of the Zuma period. Citizens have a role to play in removing these impediments. If citizens seek an emancipatory outcome, they need to actively work for this, wherever they are, and not simply look to government. By RAYMOND SUTTNER.

This article first appeared on Creamer Media’s website: polity.org.za

The election of Cyril Ramaphosa as ANC president in December evoked high expectations from a range of quarters in South African society, because it was seen as a break from the Zuma years and various expectations arose over what this entailed. That victory, as many have indicated, was also bedevilled by complex dynamics within the ANC and strong contestations. It is important that we read Ramaphosa’s victory as part of that complicated balance of forces that was not decisive and, of necessity entailed some deal making, compromises and constraints. Many people find it difficult to deal with the existence of constraints. They feel that Ramaphosa should just sweep clean all that is associated with the Zuma era. However, in intra-party politics that is much more difficult than many would like to believe.

But the biggest test is going to be what the current leadership does with the power that it has and the opportunities that exist and whether it maximises that power and negotiates around the obstacles. The question will be whether the Ramaphosa-led government will be able to do this in a manner that affirms the rights and accountability to all people living in South Africa, deriving from a renewed respect for legality and constitutionalism.

Nevertheless, in the period that followed the ANC conference, even before Ramaphosa displaced Jacob Zuma as state president it was clear that he was able by his presence and by the sense that fellow politicians and many officials came to feel, irrespective of their support for Ramaphosa -that he represented the future. And their futures were tied to him. That may explain some of the more professional actions of the Hawks and the NPA and stronger actions taken against deviant SoEs and the grilling of some former ministers, who were associated with the Guptas. (This had, admittedly, started earlier, in Parliament, and may have been part of the groundswell leading to Ramaphosa’s election).

Ramaphosa, when elected as president of the country, we know, increased the pace of regularisation of state functioning and put key ministries into the hands of people committed to reducing debt, curbing irregular expenditure and ensuring that the cancer of State Capture was eradicated.

The law enforcement agencies made arrests and brought charges and launched raids on Gupta supporters, including the offices of the Premiers of the Free State (now the Secretary General of the ANC, although he has not yet relinquished his premiership) and of the North West province.

At the same time there were continuities in that the cabinet was not cleansed of all associated with the Guptas or other irregularities and even dire incompetence. Many were bitterly disappointed in the allocation of Cabinet posts to some of the most tainted ministers of the Zuma era.

Some of these contestations can be seen in the manner in which law enforcement agencies have sometimes functioned, without full dedication to the pursuit of irregularity and State Capture. In the first place, even though the Gupta brothers and Duduzane Zuma were or may have been suspects for future cases, none were prevented from leaving the country and although Ajay Gupta is now officially a fugitive from justice it turns out not only that he has left the country, but that he and at least one other brother has more than one South African passport.

This erratic commitment to legality is also manifested in the serving of summons on leading former SARS officials who were associated with the fake “rogue unit”, last week. (The “rogue unit” and many related allegations had been shown to be non-existent by extensive investigative reporting conducted by amaBhungane, Scorpio and others). At the same time, while evidence has been painstakingly assembled of irregular or criminal action by the Commissioner of SARS, Tom Moyane and the ludicrous disciplinary hearings that purported to have cleared his deputy, Jonas Makwakwa, they both remain free of any charges. (See the series of articles in Daily Maverick by Pauli van Wyk).

This again is not cut and dried for SARS will come under scrutiny, with Moyane scheduled to appear before a parliamentary committee this week.

All of this indicates the necessarily uneven character of the Ramaphosa led “new dawn”, deriving from intra-ANC contestations. This has seen the taking of important steps to rectify the wrongdoing of the Zuma period, but then stepping back from a complete clean up, or actions taken that run counter to that goal, by the same organ of state or a different organ, engaging in actions that appear to be in support of Zuma supporters.

The political leadership as well as a range of organs of state are critical in deciding whether or not we achieve a “new dawn” or whether the ruptures are offset by so many continuities from the Zuma era that the result is very mixed. In the paths they choose politicians make the crucial decisions. But it is important to recognise – if we do want to see such change – that it cannot be left to politicians alone, in the ANC and anywhere else. Determining the future course of our state, whether or not it takes an emancipatory route is not their total responsibility. Ramaphosa and the Ramaphosa-led leadership cannot be burdened with all our expectations, with the public retiring to be observers.

If we, who live in this country wish to see a new beginning, a break from the traumas of the Zuma era, we need to ask what our responsibilities are in bringing this about, wherever we are located.

To focus so fixedly on Cyril Ramaphosa is dangerous for there are obvious limits on what is possible for him to do and not to do, as one individual. That there have been ambiguities, even very unfortunate ones are something that ought to have been expected. Zuma and the Zumaites and the culture of the Zuma era cannot simply disappear with the election of a new ANC and state president. It will live on in a range of ways that need to be carefully identified and combatted.

Even if unhappy about a range of things, citizens need to ask what they can do about them, beyond saying that Ramaphosa is not doing this or that. It is important that we do not continue to make the mistake of handing over our own power and agency to Ramaphosa or the ANC or anyone else or any other organisation.

If we look to the leadership alone to achieve all the goals and remedy all the wrongs we identify we are limiting rather than enhancing the powers they may have. If we share some or many goals with the Ramaphosa-led government, we can enhance their power to achieve these goals by actively backing what they do, ensuring that it represents what we want to see in our country. If we use our own agency, whether as students, teachers, lawyers, doctors, nurses, workers, unemployed and landless, business people and others we can strengthen the hands of the current leadership one way or the other. By our active interventions as members of society or members of organisations in society, we can contribute towards the resolution of pressing issues, like the current debate over land. Our contribution can help sway government and the public towards solutions that benefit the landless as well as the well being of the country as a whole. I mention the land because it is by no means clear how land reform is to be achieved, beyond noting that it is necessary to remedy a situation where, until now, government has devoted very limited resources towards that end. It is our job as citizens in entering such debates or making public submissions to Parliament or other institutions, to press for ways of resolving problems that empower the poor and the landless, in the context of food security, economic growth and development.

The ambiguities within the ANC will remain, at least for now, and have to be addressed by the ANC. These are internal contestations and we do not have to position ourselves in relation to the groupings contesting those issues. What we need to ask is how the contestations affect us as a people and if we find that the contestations are leading to irresoluble blockages in the way of transformation, our future cannot be tied to that of the ANC. We then need to be able to draw on stronger social movements, comprising a range of sectors of society in order to remove the obstacles ourselves or contribute decisively towards ensuring that what needs to be is in fact done.

Consequently, in supporting the steps towards regularisation and restoring legality introduced by the Ramaphosa-led government and its actions towards transformation, we do not abandon our critical faculties. There is no indication that Ramaphosa expects unconditional support from the people of South Africa. He knows that he must earn respect and backing.

What we need to do if we want to rid our country of State Capture and other fraudulent and irregular activities is not to rely only on what government does or does not do, important as that may be. We have entered a period where the contestation within the ANC may open up new possibilities for the people of South Africa to be heard and to have their displeasure and aspirations reckoned with.

This is not the time to derive our stances through notions of ideological purity. If we want to see change we have to work with what is in front of us, not imaginary, ideal conditions. Some may say that we need a total break with the Zuma era and support nothing done by government until that has happened. But in politics, there are never complete and absolute breaks. When one sees the opportunity for a transformatory route, the public can by their actions, wherever they are, help bring it to fruition. A hands-off approach, achieves nothing and in fact weakens the potentiality for substantial change.

In this complex period, we face a situation where individuals, organisations and political parties may well find grounds for co-operation while nevertheless disagreeing on many matters. We are in a terrain where there is a possibility of engagement between those who wish to see power deployed in one or other progressive way and those in government. If one wants to influence the direction taken, one must engage and be closer to decision making processes of the day. In relation to land, we know that there will be a committee embarking on a consultation process around the country. This is but one example of a potential interface between government and those who want government to take one or other direction.

The downfall of Zuma did not derive from the ANC alone but from a range of sectors who came out into the streets and voiced their opposition in a number of ways. Civil society – in its various manifestations – had also been instrumental in stopping some very oppressive legislation.

That popular power needs to be organised in order to give impetus to a post-Zuma era that needs to address the many problems deriving not only from Zuma but from the entire post-apartheid period. Popular mobilisation and organisation must continue to be deployed in order to hold government accountable. But it is also needed in order to influence the direction that it takes.

Important as it is to stress the popular, that ought not to signify any neglect of other avenues for realising, defending and advancing rights, either through the courts or other avenues open to the populace in this country.

In advancing rights for ourselves as citizens, we may sometimes or often coincide in our aspirations with that which government wants to see, sometimes not. In either case, it is important that we do not spend our time focusing on Ramaphosa but look also or primarily to ourselves in order to make maximum impact towards an emancipatory outcome. DM

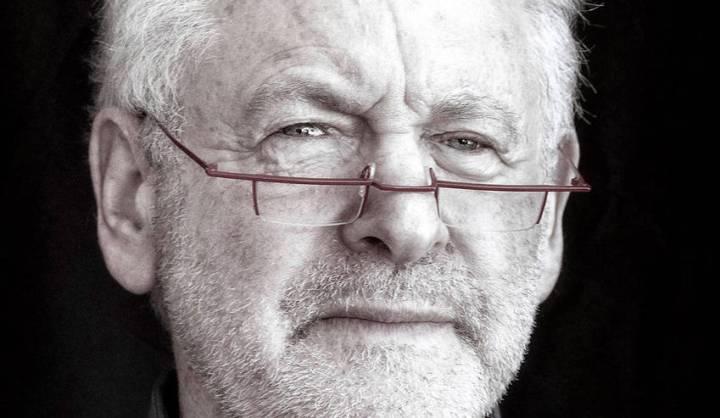

Raymond Suttner is a scholar and political analyst. He is a visiting professor and strategic advisor to the Dean of the Faculty of Humanities, University of Johannesburg, a professor attached to Unisa and (until the end of March) Rhodes University. He served lengthy periods in prison and house arrest for underground and public anti-apartheid activities. His most recent book Inside Apartheid’s prison was reissued in 2017. He blogs at raymondsuttner.com and his Twitter handle is @raymondsuttner

Become an Insider

Become an Insider