South Africa

Op-Ed: Reimagining education while learning from our mistakes

Twenty years into our new democracy, it is important to take stock of the progress we have made in changing our education system. By WENDY NGOMA.

Reimagining Basic Education in South Africa: Lessons from the Eastern Cape is the result of a Mapungubwe Institute for Strategic Reflection (MISTRA) research project, set to launch in East London on 7 November. The research report set out to explore the roles of politics, governance, accountability and power in transforming the education systems inherited from apartheid.

The Eastern Cape was chosen as the place to start, because it reveals so clearly the fault lines established by apartheid and colonialism. It’s a region of vast settlement with a few urban sprawls, and the post-1994 education department there had to merge six racially or ethnically classified semi-autonomous departments of education in post-1994 public reforms. Among these were two Bantustan (homeland) systems of education, under the former Ciskei and Trankei, as well as separate departments for Africans located outside of these “states”, and for the white, coloured and Indian communities.

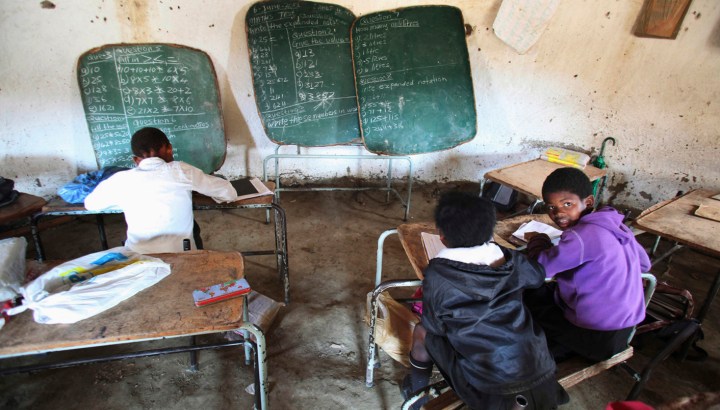

One of the distinguishing features of the Eastern Cape is that – despite the missionary education at the beginning of the 20th century – it still has low literacy levels. This low level of education contributes to, and is perpetuated by, high levels of poverty. Seventy percent of the seven million inhabitants are classified as poor (StatsSA, 2014); 64% live in rural areas; 41% of those employed have monthly earnings of less than R400 per month.

In South Africa’s inter-governmental fiscal relations, provinces have limited revenue-raising and -borrowing capacities. They are dependent on a national pool of revenue which is allocated using an equitable distribution formula. However, these allocations are hardly adequate to address the legacy of apartheid. National directives require that provinces spend at least 85% of their revenues on the health, education and welfare sectors. In the 2015/16 budget allocation for the Eastern Cape, education received the largest share of the amount of R29,438-billion.

Studies on equity in education cited in the book reveal that inherited economic disparities have affected the quality of education improvement in the Eastern Cape. The most affected are the old Transkei and Ciskei regions. While the post-1994 integration was essential for the new democratic dispensation, one cannot underestimate the legacies of these previous regimes and the divisions they created. Chapters in the book show the extent of reliance on patrimonial bureaucracy, which survived on “clientelist” networks. The culture of separation had in one way or another created distinct identities and cultures, which could not be written off overnight. All previous structures had over time developed their own ways of doing things and had created their own practices in response to their supposedly unique environments and contexts.

One of the key issues raised in the literature, and discussed in the book, is that, common to all the homelands, the public services lacked skills to run an efficient bureaucracy and it was prone to corrupt and nepotistic tendencies due to the patriarchal system that dominated homeland governance in general. Hence it remained a challenge to integrate the new bureaucracy into a fully effective delivery machine.

The Eastern Cape Department of Education (ECDC) drew its mandate for transformation from various government policies and regulations. At the beginning the Interim Constitution of 1993 and the White Paper on Public Service Transformation (1995) became the major points of reference, followed by other newly developed policies which all had differing impacts. These include the White Paper on Education and Training (1995), National Educational Policy Act (1996); the South African Schools Act (1996) and the Public Finance Management Act (1999). While almost all these policies were based on the normative values of equity, redress, quality and access, the way they were interpreted depended on the local conditions.

In the ECDE, the national department of education provided the overall policy framework and relevant policy directives. This was in line with the constitutional provisions that national departments had concurrent and even overriding powers over provincial departments. Hence the provincial departments tend to follow policy directions set by national offices, despite their autonomous status.

With the furious pace of reform from 1994, national policies became major drivers for change; sometimes with little or no conceptual alignment and co-ordination between the national and provincial offices. While this disjuncture could be explained by the urgency to change the system, in retrospect one could argue that this approach affected the provincial department’s ability to plan, co-ordinate and streamline their own internally driven reforms. Structures to facilitate inter-governmental relations, including ministerial-MEC forums, took time to gel.

The brief context provided illuminates the contextual realities of early reforms in the ECDE, and the opportunity to take stock of how 1994 reforms shaped educational change in the Eastern Cape. The reality is that the ECDE still suffers from leadership challenges, with high levels of instability at the top and poor performance outcomes.

Since 1994, the failure to implement agreed policies has manifested at various levels and in a variety of ways. These include the collapse of management, teaching and learning, monitoring and evaluation and school nutrition schemes in the Eastern Cape. Consequently, the national government invoked relevant sections of the Constitution to take over the running of the provincial departments of education – and in the Eastern Cape, this has happened over three periods, in 2004 -2005, 2006-2007 and again 2011-2013.

The Eastern Cape experience has been used to interrogate the reasons behind the failures and successes of such interventions in order to think forward towards Vision 2030 and to the implementation of the National Development Plan. This volume aims to examine the reasons why things may not have changed in the Eastern Cape in the last 20 years, and to give as much clarity as possible on what has worked there. The success stories, set amid the challenges of lack of resources, poor capacity and poor infrastructure, can be replicated in other contexts with similar conditions and constraints. DM

Professor Wendy Ngoma is the Project Leader of the Mapungubwe Institute for Strategic Reflection’s (MISTRA’sa) research report on education.

Photo: Children write notes from a makeshift black board at a school in Mwezeni village in South Africa’s Eastern Cape province. Picture taken June 5, 2012. REUTERS/Ryan Gray

Become an Insider

Become an Insider