Africa, South Africa

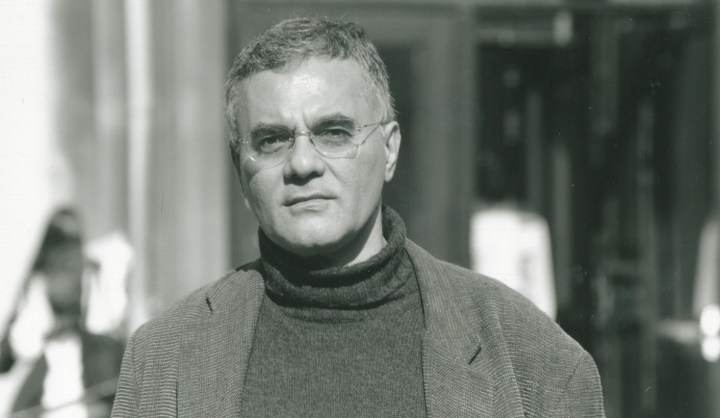

Mahmood Mamdani: Sixteen years on, UCT’s old nemesis returns to talk decolonisation

The last time celebrated Ugandan scholar Mahmood Mamdani set foot at UCT was 16 years ago. Mamdani left UCT swearing never to return after clashing with the university over his attempts to “decolonise” its curriculum. This week, he was back to deliver UCT’s TB Davie Memorial Lecture on academic freedom, on a campus still wrestling with the same issues more than a decade-and-a-half later. By REBECCA DAVIS.

When someone asked Professor Mahmood Mamdani why he had decided to return to an institution with which he famously cut ties 16 years ago, his reply was simple: “Because Rhodes fell”.

Back in the late 1990s, Mamdani tried to spearhead a process of academic transformation at UCT which ended badly. The “Mamdani Affair”, as it came to be known, culminated in Mamdani’s suspension and eventual resignation, with the scholar terming UCT’s Centre for African Studies “a new home for Bantu education”.

When UCT Vice Chancellor Max Price introduced Mamdani to the audience at UCT on Tuesday night, Price’s reference to the Mamdani Affair prompted heckles that an apology to Mamdani was overdue from the university. Price stopped short of an outright apology, but acknowledged: “As an institution, we are poorer for having lost academics of his calibre.”

Student activists in the audience deemed this insufficient, with Fallist Chumani Maxwele later declaring from the floor: “It is not surprising that Dr Price will not apologise to [Mamdani]. We will wait for another 40 years… to acknowledge the institutional and systemic racism that black people suffer at the hands of white people.”

Mamdani himself, however, showed no appetite for point-scoring with reference to the past. He dwelled only briefly on his time at UCT, at the end of his address, describing it as “lonely” but “a great learning experience” – because it meant he began to think yet more deeply about practical ways in which to decolonise African universities.

Today Mamdani splits his time between Makerere University in Uganda and Columbia University in New York, so his is a truly global scholarship. In his address, tackling the issue of decolonising the university, he drew on his experiences as a young scholar in both Uganda and Tanzania, and the debates that raged in East Africa shortly after independence.

In these countries, Mamdani said, tensions over the role of the university in postcolonial Africa were framed as one of excellence versus relevance. Should such institutions produce “universal scholars”, equally at home at Oxbridge or the Ivy League as in their African universities; or “public intellectuals”, deeply rooted in the politics and social context of their African setting?

It should not be a choice between one or the other, Mamdani contends. “Obviously, place matters,” he said. “If universities could be divorced from politics… then place would not matter. But we know that’s not the case. At the same time, ideas do matter.”

Mamdani reminded the audience that universities were “in the frontline of the colonial civilising mission” in Africa and elsewhere. “The university was the original structural adjustment programme,” he suggested.

Key to the colonising mission of colonial universities was their insistence on the use of English as the medium of scholarly thought. Mamdani says that the legacy of this policy remains with us today, leading to a situation where it is not possible to speak of “an intellectual mode of reason we can term African”.

African languages have remained “folkloric”, Mamdani said: not the bearer of a scientific or scholarly tradition. But there is one noteworthy exception on the African continent: that of Afrikaans.

“It is no exaggeration to say that Afrikaans represents the most successful decolonising initiative on the African continent,” Mamdani said, to murmurs of interest from the audience. He pointed out that it took just half a century of a “vast affirmative action programme” for Afrikaans to be lifted from the status of other African languages to be the bearer of an intellectual tradition.

“The great irony is that [this success story] was not emulated by the government of independent South Africa,” says Mamdani, with reference to other indigenous South African languages.

To Mamdani, the task of decolonising African universities is inextricably tied up with the need to develop African languages. “The decolonising project has, by definition, to be multilingual,” he said: “To provide resources to nurture and develop non-Western intellectual traditions.”

He called on institutions like UCT to establish proper centres for the study of African languages and to spearhead efforts to translate global literature into these languages. It is only in this way, Mamdani suggested, that African universities can stop importing Western theories to impose on local experiences and instead “theorise our own reality”.

Turning to Vice-Chancellor Max Price, Mamdani acknowledged that these steps would cost money. “This is not the time to think like an accountant,” he urged. “This is the opportunity to change direction, from the outpost of a colonising mission to a platform for the decolonising project. If you make that decision, you will certainly not be alone.”

Mamdani also had words of support for the #FeesMustFall movement, saying that South Africa was an aberrant case in Africa because the cost of university education rose after independence rather than falling.

“Affordable higher education must become a reality if the end of apartheid is to have meaning for the youth,” Mamdani said, to cries of approval.

Before Mamdani’s address, a number of UCT academics – including Philosophy Professor David Benatar – had called on him to decline the opportunity to speak at the university in solidarity with the fact that last year, UCT withdrew its invitation to controversial Danish editor Flemming Rose to give the annual free speech lecture after protests.

Rose was responsible for the 2005 publication of cartoons of the Prophet Muhammad in the Danish newspaper Jyllands-Posten, one of which depicted Muhammad with a bomb in his turban. Rose has since become a free speech advocate, and some see UCT’s 2016 decision to bar him from delivering an academic freedom lecture as hypocritical.

Mamdani came prepared to address the matter. He asked whether the UCT academics who were vocal in support of Rose’s invitation would feel as warmly towards an address by the publishers of anti-Semitic cartoons in Nazi Germany, or those artists who incited the Rwandan genocide.

Terming Rose “Islamophobic”, Mamdani affirmed Rose’s right to free speech.

“But there is no democratic right to give the academic freedom lecture at UCT,” Mamdani said. “It’s not a right; it’s an honour, and Mr Rose does not deserve that honour.” DM

Photo: Ugandan scholar Mahmood Mamdani returned to UCT for the first time since he clashed 16 years ago with the university over his attempts to ‘decolonise’ its curriculum. Photo: Wikipedia Commons.

Become an Insider

Become an Insider