Maverick Life, South Africa

Book Review: Shaping the present through the nobility of our past

For me, Charlotte Maxeke’s story is testament to the beauty of biography as a literary form. The story of a person’s life is a way to prise open the history that made her and which she in turn made. In the pages of Beauty of the Heart you can travel back to Ramokgopa village in Limpopo in the mid-nineteenth century where her father came from; visit and feel the diamond fields of Kimberley in the 1890s; make passing encounter with Olive Schreiner and Emily Pankhurst; and be reminded about the indignities inflicted on Sarah Baartman. By MARK HEYWOOD.

In 1893, as the young Charlotte Maxeke prepared to return to Kimberley after two years in England she had these parting words of advice for her English hosts:

“Let us be in Africa even as we are in England. Here we are treated as men and women. Yonder we are but cattle. But in Africa as in England we are human. Can you not make your people at the Cape as kind as your people here? That is the first thing and the greatest. But there are still three other things that I would ask. Help us to found the schools for which we pray, where our people could learn to labour, to build, to acquire your skills with their hands. Then we could be sufficient unto ourselves. Our young men would build us houses and lay out our farms and our tribes would develop independently of the civilisation and industries which you have given us. Thirdly give our children free education. Fourthly shut up the canteen and take away the drink. These four things we ask of the English. Do not say us nay!”

Needless to say the advice of a young black African woman was ignored.

The rest is history.

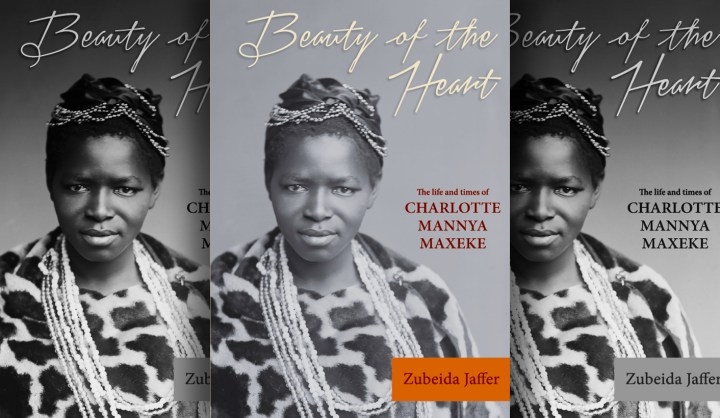

This year the life and advocacy of Charlotte Mannya Maxeke has been brought back to life by writer and activist Zubeida Jaffer. By doing so Jaffer has done our country a great service. As a result of her efforts to excavate the life of this lost heroine, hopefully, inquisitive generations of the 21st century can embark on a road back into the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Through this work, new generations of feminists, men and women, can find out about this pioneering activist, now better known as the name of a Johannesburg hospital.

A well written book is a wonderful thing.

Beauty of the Heart is a beautiful book. It is the type of biography I would use to persuade children (and adults) of the riches and rewards of reading. You take a name, one of the first women in the world (never mind the first African woman in South Africa) to be awarded a degree, and through reading about her life you embark on a totally unexpected journey into our past. Through our past you reach a better understanding of our present, you find tributaries to the flow of politics and society that either turned into great rivers, or were prematurely stilled.

For me, Charlotte Maxeke’s story is testament to the beauty of biography as a literary form. The story of a person’s life is a way to prize open the history that made her and which she in turn made.

In the pages of Beauty of the Heart (ZJ Books) you can travel back to Ramokgopa village in Limpopo in the mid-nineteenth century where her father came from; visit and feel the diamond fields of Kimberley in the 1890s; make passing encounter with Olive Schreiner and Emily Pankhurst; be reminded about the indignities inflicted on Sarah Baartman.

As you turn the pages of the book your imagination is aided to travel with Charlotte and her sister Katie to England with their choir (which they had called the Jubilee Singers but their British hosts insisted on marketing as “the K….r choir”); witness them as they meet the British monarch Victoria whose granddaughter, at the end of the choristers’ performance, reportedly tugged at the great matriarch’s sleeve, saying: “Granny, Granny, come away, I don’t like these darkies.”

That such telling snippets of history even exist is a wonder of writing history.

Through the beauty of the book you accompany Charlotte to the Northern English city of York, as it was in 1894, where Charlotte’s choir chanced upon a mixed race choir from America who, oh great surprise, “seemed to treat each other as equals”. It was from them that Charlotte first heard of Wilberforce University, the first university owned and operated by African-Americans and then developed her mission to find her way there – which she did three years later.

Through the beauty of the book you bump into an eclectic array of men and women, witness their strange meetings and the impact that chance and fleeting encounters can have on the course of history. You will encounter James Stewart, the second principal of Lovedale College (who bailed the choir out when they ran out of money in England); the great pan-Africanist WEB Du Bois, a teacher at Wilberforce University where Charlotte got her degree in 1901; the reclusive Pallo Jordan will surface in footnotes commenting to Jaffer on the great African-American intellectual traditions. (The story of the Jordan family, his father AC, mother Priscilla Ntantala and Pallo himself is another biography South African’s deserve.)

Through the beauty of the book you will get to sit alongside Charlotte as the only woman delegate at the founding conference of the SANNC (later to be renamed the ANC) in 1912; you will bump into Pixley Ka Seme, Walter Rubusana, Sol Plaatje and AB Xuma. You will see her as a leader of the Bantu Women’s League, an organisation that maintained a steadfast independence from SANNC; then you will be privy to early divisions within the ANC, between radicals and moderates, men and women, proponents of non-racialism and exponents of racism. The divisions we lament today were there a 100 years ago. We have been going in circles ever since.

Finally, on the very last page of the book, almost as an after-thought, you will encounter a post-script by Andre Kriel, the General Secretary of SACTWU stating that “Charlotte’s life will provide an inspiration to those determined not to give up on the dream of a better life for all”. He advises: “We should take this book into our factories and workplaces, so that workers will have the opportunity to make this story part of their lives.”

Would that we did just that!

Would that we reinvigorate the traditions of reading and learning that animated people like Charlotte. Would that we revive the desperate quest for ideas and education, that motivated the first generations of African revolutionaries and Pan-African activists. Would that we use the story of Charlotte Maxeke not as the name for a hospital but as reason to reject the the burnt offerings of basic education offered up by our captured government to the young and poor!

Beauty of the Heart makes me proud of our South African journey, it makes me want to be part of reinvigorating a belief in reading, teaching and learning to make it relevant to our present, and above all to inspire people to identify with the nobility of our past as a reason for shaping our present. DM

Become an Insider

Become an Insider