Maverick Life

South Africa’s Special Songs

Reviewing David Coplan and Oscar Gutiérrez’s new volume on the Bassline and Renée Reznek’s newly released CD of contemporary South African piano music, J. BROOKS SPECTOR looks for the special sound of South Africa in an age of global music. (And he is only too delighted to take a break from having to contemplate yet another political excess or bizarre bit of behaviour from people like Donald Trump or Jacob Zuma.)

Many years ago, as a young diplomat stationed in Johannesburg, our office ran a monthly gathering – the Johannesburg Music Appreciation Society. The series hosted everything musical from afternoon performances by American jazz performer Barney Kessel (working the city’s apartheid-era night clubs back in those pre-cultural boycott days) to a lecture on the Kurt Weill/Maxwell Anderson show, Lost in the Stars, based on the Alan Paton novel, Cry, the Beloved Country. Every programme filled our auditorium with (mostly) black South Africans eager for entertainment, information, and new ideas about music.

But, especially whenever guitarist/flautist Philip Tabane and traditional percussionist Mabi Gabriel Thobejane – Malombo – came into town and agreed to do a gig for us, just by word of mouth, attendees mobbed our offices, eager to be part of that lucky crowd. People filled every available space in the auditorium; they sat in the hallways and on the stairwell. They even waited in the library, eager to be able to hear even the faintest sounds produced by the renowned Malombo group, only recently back from the US as Miles Davis’ opening act.

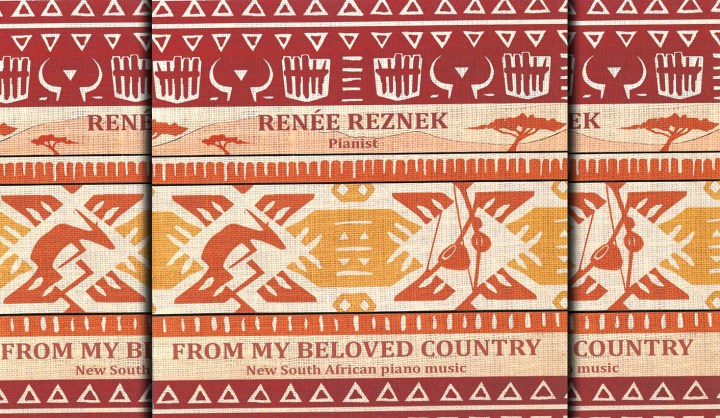

Photo: Renée Reznek

Of course, Malombo gave astonishing performances in vast arenas and university great halls. There was something extraordinary about them in the 1970s. And as much as they enthralled audiences, as performers, they were clearly delighted and enraptured by their own music as well, and their performances were almost mystic. And in much smaller, more intimate gatherings where one could sit closer to them, even their fingerings had a kind of tantric, mesmerising effect on one, well beyond the unique sounds they produced.

David Coplan and Oscar Gutiérrez’ new book, Last Night at the Bassline, has triggered those long-ago memories of Malombo, in part because Tabane also figured in some memorable performances at the Bassline. We once had such a chance to catch the uniqueness when, in a show at the Bassline, Tabane’s improvisations around that old British folk tune, Country Gardens (arranged by many folk singers and even a classical composer like Percy Grainger), spiralled out so distantly from the original music that Tabane’s accompanist on African percussion simply froze on stage, unable to join in until Tabane deigned to reel back his musical ideas just a bit more to this world.

Tabane comes to mind at this time, in part, because of those performances, and because co-author David Coplan actually performed with Tabane and Thobejane back in the 1970s in concerts around South Africa when Coplan was in this country for the first time as a graduate research student, coming here from the United States. Over the years, in his academic day job as a cultural anthropologist, Coplan had carried out examinations of the lives of Basotho migrant workers, as well as producing other writing such as the rigorously researched and much cited examination of South African urban black culture, In Township Tonight.

Now living permanently in Johannesburg, Coplan has watched the music scene as a participant observer for decades. His easy, comfortable familiarity with everybody in that world as they passed through the doors of the Bassline has been one result. Meanwhile, Gutiérrez’s photographs – really a full photographic essay of the venue’s history and the many musicians who performed there and passed through its doors – are warm and inviting, almost as if they are a window into a world that has just lately vanished.

Gutiérrez, also a migrant to Johannesburg, came to document the Bassline by a circuitous route that began in Guatemala, then moved on to his becoming a photographer for Nasa in the US. Then it was on to South Africa in 1994 where, among other things, he ended up as translator/escort for the Cuban delegation coming to the inauguration of Nelson Mandela as president. And he has been documenting South Africa’s cultural life since then.

The Bassline began just as the infinite possibilities of a new world unveiled in South Africa’s transition from the dying embers of the apartheid era gave hope to many that a new, warmer, and more encompassing cultural and social order was being born. As Coplan writes of this cultural “brave new world”,

“Brad ‘Sheer Luck’ Holmes, the accidental musophile [and founder of the Bassline], calls 1994-2003 ‘The honeymoon decade’. Just before, 1989-1993, the wheels of the Old South Africa had come off. Then the wraps came off. ‘Vive L’Interregnum!’ said historian and sage Charles van Onselen….”

In that space, the Bassline took over the top spot for a jazz club in Johannesburg from the Kippies venue in Newtown – especially after Newtown slid heavily into the crime and grime business from the mid-1990s onward, and then, later, especially after Kippies was shuttered by the city over some perhaps-mythic building structural issues.

Opening up on one of the Melville neighbourhood’s main streets, the Bassline was actually a small, cramped venue. It had largely jury-rigged sound equipment, an interior that had been pulled together out of whatever had come to hand, some rather uncomfortable chairs for patrons, a kitchen that probably should have been barred from serving food, and an improvisational management style that, in ordinary circumstances, would have virtually guaranteed its nearly immediate and ignominious failure. But, instead, the exact opposite happened.

The Bassline became a favoured, even revered, near-cult venue for people seeking the new musical path of a nearly new nation, and even inspired a live recording CD series. The club thrived creatively for years under its founder-operator, Brad Holmes, even if it never proved to be an enormous commercial success for him. Ultimately, Holmes took a second chance and moved into bigger quarters in a slowly reviving Newtown; but the music business can be a fickle mistress. However, this newest incarnation never took root with fans in quite the same way his old Melville club had done with so many music fans.

In his introduction to this book, music entrepreneur Sipho Sithole wrote of the club,

“Coplan details a story of a people flocking back to the city in search of the broken strings of Allen Kwela, and those looking for first-hand experience of a live jazz performance only to fall prey to Zim Ngqawana’s chastising zimphonic rules of silent conversations in the consumption and appreciation of his musical rendition.

“The book lets the reader into how a world of music and a venue that knew no borders, with its anti-xenophobic stance and multiculturalism, opened its doors to patrons of all creeds and musicians from the diaspora such as Louis Mhlanga, Oliver Mtukudzi, Gito Baloi, and from the rest of the world, while bringing Carlo Mombelli, Abdullah Ibrahim, Dorothy Masuka, Hugh Masekela and many more back into the country. A book that talks of a place where the departed spirits of Lulu Gontsana, Gito Baloi, Bheki Mselelu, Moses Molelekwa, Johnny Fourie, Sipho Gumede and George Phiri are busking at the entrance of Bassline waiting for the doors to be flung open for one last time….”

Performances at the Bassline were often more than just straight jazz. Any venue that featured the likes of Carlo Mombelli on one night, Abdullah Ibrahim the next, and then the late Aaron “Big Voice” Jack Lerole on another one was a whole lot more than just a jazz club, but we have to call it something, so as a jazz club it shall be remembered.

Coplan, in contrast to his more academic style of anthropological writings, and even the approach of In Township Tonight, has produced a volume in which the research is there, but it is delivered like an extended freewheeling conversation between two old friends who know things. It becomes a commentary that sounds like, “Hey, it’s 3am and maybe we should go home now, but, say, maybe just one more beer and a little more talk, and then we really will understand the universe finally.” Think of it as something like what anthropologist Margaret Mead would have sounded like – if she had taken up the stylistic and social conventions of, let’s say, Hunter Thompson.

The book explores the shaping of Brad Holmes’ life and his eccentric, electric background, the social circumstances of a changing Melville, the South African music industry, and the rapid social transformation of South Africa as a whole, back in the 1990s. But, first and foremost, the book embraces the musicians and their music that made the Bassline synonymous with being “hip” and “with it” (or whatever we call it now) in the Johannesburg of the “New South Africa”.

Last Night at the Bassline is a great way to reminisce about the things that were, and those that might have been. But, as you read it, have a glass of something nice and smooth in your hand, and some good music playing softly in the background. The only regret about this book is that it doesn’t also come packaged with a CD selection offering some of the best cuts from “Live at the Bassline” recordings.

In contrast, Renée Reznek’s new recording, From My Beloved Country, offers solo piano works from eight of South Africa’s most interesting composers in the contemporary “classic” vein. This roster includes artists as varied as Neo Muyanga, Kevin Volans, Peter Klatzow and David Kosviner. The individual pieces reveal a startling range of influences on contemporary composition in South Africa – from traditional African rhythmic styles and echoes of traditional chants and choral singing, the mbira hand piano, and even the uhadi stringed instrument, along with musical quotations from Debussy, Sinding and others more familiar to many piano students. There are even echoes of Nelson Mandela’s stately and formal walking tread, and a musical response to the recent #FeesMustFall student crusade.

Back when Reznek was at the University of Cape Town, her fellow students had marvelled at her technique and enthusiasm for tackling the most intricate and complicated contemporary piano music, rather than all those gallant warhorses from the romantic and classical periods. People in university remember her as a pianist with the kind of precision that allowed her to grapple with the compositions of composers like Arnold Schoenberg, Alban Berg or Anton Webern – without flinching.

And her love for the piano came early. As she told an interviewer recently, she was first introduced to the piano at the age of four by an elderly relative. Those home performances brought her to tears and to the realisation that she had found her path.

In that interview, she added,

“I grew up in South Africa where very little 20th century music was performed. However, when I was a B. Mus. student at the University of Cape Town, my Harmony and Counterpoint lecturer, now Professor Emeritus James May, asked me to play Schoenberg’s Suite Opus 25 and Webern’s Variations Opus 27 in a concert. Despite not knowing these pieces at all and initially finding them incomprehensible, I was determined to honour my commitment and in the process became ‘hooked’. What fascinated me in the Suite for instance, was recognising the phrasing of a Gavotte or Minuet despite the unfamiliarity of the serial language. This felt exhilarating, like learning a new language. So thanks to James May, this was the start of my journey into 20th century and new music.”

Later advanced musical study in the US and the UK, where she now lives, only reinforced her chosen direction in her musical commitment.

In speaking about this new recording, Reznek says,

“I am proud of my new CD of recent South African piano music which I hope will introduce some fantastic composers to those unfamiliar with South African contemporary music: Kevin Volans, Michael Blake, Rob Fokkens, Neo Muyanga, David Earl, Peter Klatzow, Hendrik Hofmeyr and David Kosviner. The majority of the pieces on the CD are rooted in traditional South African music though some are European in origin; this is diverse repertoire, which reflects a rich and varied culture. With one exception, these works have never been recorded and many have been dedicated to me.”

On this recording, while Neo Muyanga’s Hade, Tata (Sorry, Father) pays homage to African traditional sounds and harmonies dealt with in particularly untraditional ways; Michael Blake’s Broken Line recalls the music of the uhadi; and David Kosviner’s Mbira Melody II embraces the textures of the ubiquitous hand piano of southern Africa (along with what seems to be something of a nod to the minimalist sounds of, say, a composer like Terry Riley), other works reach out to other inspirations and sources. Kevin Volans, perhaps South Africa’s best known composer – at least abroad – pays homage to his own compositional mentor Karlheinz Stockhausen, to Christian Sinding’s once-popular Rustle of Spring, and includes references to Claude Debussy’s L’Isle Joyeuse. Volans said of his composition that he made that last quote more technically difficult than the original was, in a kind of musical “retribution” to Reznek for having once beaten him in a piano competition during student days. Two other composers, Peter Klatzow and David Earl, deconstruct and reconstruct the gentle dance-like barcarolle musical form.

While many of these works might not have been at home in the Bassline, or with many of its usual patrons, at the same time there is a clear line of connection between much of this music and the compositions of such one-time Bassline performers as Abdullah Ibrahim and Carlo Mombelli. (In fact, it might even have been interesting to have included an Abdullah Ibrahim composition on this recording as well in order to make that precise point to listeners.) Yes, jazz and its musical relatives are presumed to be more improvisational in contrast to the fully composed works represented on this album, but even some contemporary classical music does include improvisational and chance elements in it. This further smudges the dividing line between the two spheres of music.

Despite the sometimes-austere aspects of some of the music Reznek performs (and the sense some may bring to it that this music is just too far beyond their musical tastes for them to appreciate), as a collection it becomes increasingly rewarding as one listens to it repeatedly. As a performer she has obviously curated this disk with care, thought and attention to the many divergent strands of South Africa’s musical heritage – and, importantly, to the ways these influences and ideas have been used and woven together by the best composers the country now has to offer. Buy it, listen to it, and learn from it.

Perhaps give rock ‘n’ roll genius Jerry Lee Lewis the last word on this question of the crossoverness of music these days. Lewis says, “Normally, things are viewed in these little segmented boxes. There’s classical, and then there’s jazz; romantic, and then there’s baroque. I find that very dissatisfying. I was trying to find the thread that connects one type of music – one type of musician – to another, and to follow that thread in some kind of natural, evolutionary way.” In their own way, these two new items, a book on the Bassline nightclub and a recording of some of the most interesting contemporary “classical” piano music coming from South Africa, try to do exactly the same thing. DM

Last Night at the Bassline, by David Coplan and Oscar Gutiérrez, Jacana Books, ISBN 978-1-4314-2499-3, www.jacana.co.za

Renée Reznek, From My Beloved Country, Prima Facie, PFCD055, available from Music 4 U, [email protected]

Become an Insider

Become an Insider