South Africa

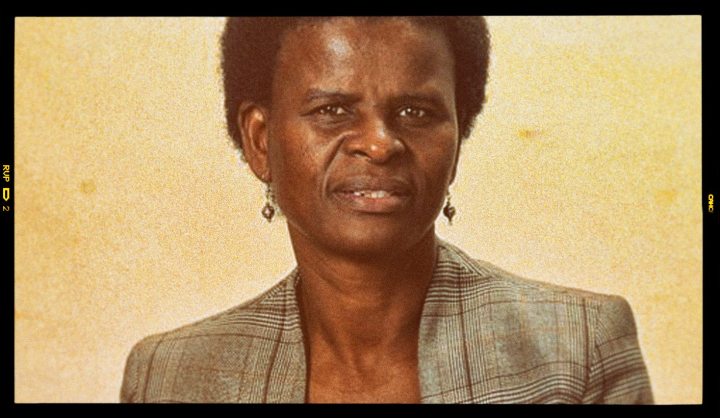

Many Rivers to Cross: Bridget Masango – from barefoot schoolgirl to Parliament

Bridget Masango in many ways represents the triumph of democracy in South Africa. She is the sixth of nine children, born at the height of apartheid in the 1960s. Her father was forced to leave rural KwaZulu-Natal to work as a security guard in Johannesburg while her mother was a child-minder for a farmer, working in the farmhouse kitchen when she was not tending her own patch of land to keep her family alive. Masango knows the humiliation of poverty, the dompas, of being “illegal” in the cities of her own country. But from an early age Masango did not allow the considerable hurdles in her path to stop her from fashioning a life on her own terms. Today she is the Shadow Minister of Social Development, a polar opposite to Bathabile Dlamini. By MARIANNE THAMM.

An image.

It is 1976 and a 14-year-old pupil in rural KwaZulu-Natal is walking a 35km distance to the Umbiya Secondary School, along a dirt road near kwa-Mbonambi in northern KwaZulu-Natal. She is barefoot and has opted, at this point, to remove her black school shoes and white socks lest she dirty or scuff them on the long walk.

To get to school on time Bridget Masango has woken at 4am, finished her chores – fetching water and wood to fire up the Welcome Dover stove – eaten, and begun the daily trek, sometimes accompanied by her sister. Around her are rolling hills and fields of sugar cane plantations. To get to school she must cross two rivers.

“The river meandered and at the second crossing near the school I would stop and wash my feet and put on my clean white socks and shoes,” Masango, sitting in her office in the Marks Building in Parliament, recalls.

Encountering Masango now you will find undimmed echoes of that young, determined girl. The DA’s Shadow Minister of Social Development is always elegant, understated, always calm – well, at least outwardly. She shuns make-up and bling but is always immaculately turned out – a blouse, a jacket, a skirt, good shoes (not too expensive, mind you). She refuses to wear “fake hair or fake nails”.

Masango’s trajectory in the Democratic Alliance in four short years has not pleased everyone in the party.

“There are those who tell me to my face I was parachuted into the party. It doesn’t bother me,” she says with a smile.

Point is, Bridget Masango is a shining example of why affirmative action and quotas are necessary in post-apartheid South Africa. It was Mike Moriarty, former leader of the DA caucus in Gauteng, who first encouraged Masango to make herself available for a party list in 2014. In 2013 the DA understood it needed to become a party that was much more representative. And it needed more women, particularly black women.

Masango, who at that point had been working as a Communications Manager for the Nelson Mandela Children’s Foundation, had met Moriarty several years earlier when she worked for Group 5 and Moriarty was an engineer with the company. They had attended the same church, says Masango, and it was Moriarty who had introduced her to the DA. She began to help the party out with admin – making flyers, driving pensioners around.

In 2013, as the 2014 elections approached, Moriarty had asked Masango to help recruit members. She did not, she says, think that she would eventually end up a “confidential candidate” on the list.

“I mean, me in politics! No. You need to be mad to go into it. But eventually I agreed to being on the 2014 list, thinking it was impossible that I would ever get anywhere. But it did. Initially I didn’t make it because my seat was not secure. They had 25 out of 28 and I was no 28.”

Masango was sanguine about it all and returned to work. Later that week, Moriarty called again. This time he informed Masango that the DA in Gauteng had been given the opportunity to have two representatives in the NCOP. He didn’t want to get her hopes up as there had been 40 applications.

“For what it is worth, I said go ahead. I mean, here is me, this person, a newbie with no political experience and now I am competing with 39 other people! I said ‘go for it, Mike’.”

Masango was expected to “present” to the Federal Executive alongside people who had been in the party and politics for years. She didn’t think she had a hope in hell.

But on May 22, 2014 Masango found herself being sworn in by Chief Justice Mogoeng Mogoeng as a Member of the Fifth Parliament of South Africa.

In the opening chapter of a short memoir Masango has penned she describes that moment: “It is the latter part of this swearing in that brings my whole life back into perspective, in a split second. Everything I had gone through – good, bad, hilarious, downright exciting, nail-bitingly nervous and fearsome – made sense at that very moment when I repeated after the Chief Justice to finish the swearing in by saying “So help me God”. It was not the first time I had heard those words, used in movies, in plays, in all sorts of situations, but on that day it carried a brand new meaning to what had been happening in my life and why I was standing there at that very moment.”

The journey to that point for Masango had been a long and difficult one since she first distinguished herself at her lower primary school at New Phatane where she was so brilliant – at maths and science – that she was bumped up a few grades to join her siblings.

She graduated then at the top of her class and was due to sit an external examination for Form One, or Grade Six as it was known then, Grade Eight in contemporary schooling.

But apartheid South Africa was not a country for clever young black women from rural KwaZulu-Natal. Like millions of other disenfranchised South Africans, the Masango family eked out a living. There were nine mouths to feed, clothe and school – six girls and three boys.

The situation was so dire that in 1975 the young Bridget was forced to stay at home the entire year. It was this experience, she says, that sparked in her a “burning” desire to get an education. She begged her mother to let her return to school and in order to help pay the fees took up a part-time job in the small town of Mtubatuba. She was 13 years old, and it was a year before she would eventually, because of kind benefactors, find herself walking barefoot to Umbiya Secondary School along that dusty road.

“At one stage I worked at a record shop and would market the legendary ‘amaSwazi emvelo’ and the Soul Brothers with so much passion the customers would swear I owned copies of my own!”

Bridget had had an earlier brush with politics, joining the Inkatha Youth Brigade while still at school.

“My area in KwaZulu-Natal was particularly politically volatile at the time. Many people died. My brother was an IFP councillor. We were taught about Inkatha at school. I became a secretary of the party but my mother was against it. She said ‘not in this house. There is not going to be politics in this house. Tell them now you are getting out of it’,” Masango recalls.

Masango said she believes her mother may have thought she would get “carried away” as she was viewed by her family as “always exploring, doing and seeing new things”.

The DA’s Shadow Minister of Social Development has the bearing of a self-made woman although she will argue that she owes much of her success in the most difficult of times to the generosity God as well as the many individuals who crossed her path and who recognised and nurtured her potential.

One of these was the inaugural principal of Umbiya Secondary, Mr AA Biyela. It was he who – after Masango had completed her JSC (Std 8 or Grade 10) and had once again made it to the top of the class – arrived at her mother’s homestead one Saturday morning while Bridget was at work, selling stationery, records and batteries.

Because she was working six days a week, Masango had been unable to collect her brilliant results and a puzzled Mr Biyela had made a turn past her home to inquire as to why, and also how Bridget had expected to register for matric without them.

Her mother explained to Mr Biyela that young Bridget would not be continuing her studies – at least for the following year – as the family could simply not afford it.

It was Mr Biyela who tried to convince Rotary Club members to provide a bursary for Bridget. It was a bursary for another child who would not be taking it up. But rules were rules and Bridget would have to apply afresh in the following cycle. Bridget overheard the conversation and wept bitterly.

“There and then Mr Biyela wrote out a cheque for me to buy books and stationery,” she recalls.

And then another act of generosity. The woman, Ma Thandi, who worked in the venue where the Rotary Club met, witnessed Bridget’s disappointment and offered to take the young teen in. She was a single mother of four sons.

“She was a total stranger. It was incredible. I registered at Amangwe High School and spent two years with Ma Thandi and her mother Gogo Mnguni. She was amazing, ensuring that I did everything and set time aside to study – as Ma Thandi was a working mother who only arrived home after working hours.”

After matriculating, Masango ventured to Johannesburg to find work. Because of the Pass Laws, Bridget was allowed to travel only because her older sister as well as other relatives had settled there. But still, she had to carry a dompas, as it was known.

“I had no experience being in a big city at all until I arrived in Johannesburg. It was a cultural shock.”

It was there that Bridget met her husband while working as a receptionist at a hotel and later married him. She says this was the only aspect of her life where she did feel pressure to conform.

“As a Zulu woman you are expected to be married by a certain age. You are also expected to behave a certain way towards your husband. I was told that I should listen to my husband and my in-laws as it was the name Masango that would be disgraced if I did not.”

Masango found herself in rural Wasbank, where her husband’s family lived, being a Makhoti. This entailed hours of back-breaking work for her in-laws. Ploughing fields “doing work I knew well. I could span oxen like a pro”.

It was her husband’s grandmother who understood that Masango was not cut out for rural life and who encouraged her to return to Johannesburg to join her husband. By then she had given birth to her only daughter whom she left behind in Wasbank.

The marriage ended after three years when Masango’s husband had forbade her to study or to send money home to her mother.

“One Saturday morning I woke up and I left. I told him, ‘If I can’t study and can’t support my mother, then you can keep the marriage.’ And that was that.”

Within a few years, and with the help of relatives and strangers she had met along the way, Masango fetched her daughter and bought her own home. She obtained a BA in Communications and Public Administration through Unisa and worked for the construction company Group 5 before becoming the Marketing and Communications Director of the National Development Agency and the Nelson Mandela Children’s Fund.

On 15 February 2016, Masango gave her maiden speech at the 2017 SONA debate. She has made a name for herself as one of the members of the opposition, along with colleague Lindy Wilson and the IFP’s Liezl van der Merwe, who have helped to expose what was to become known as Sassagate, Minister Bathabile Dlamini’s risky gamble with 17-million lives dependent on social grants.

Back home in rural KwaZulu-Natal, everyone watched Masago live on TV, including her mother, who is now in her 80s.

An image: It is 1976, a 14-year-old schoolgirl is walking 35km to school barefoot with her cousin. It is raining. At some point a navy blue car passes the children. The 14-year-old girl turns to her cousin and tells her that one day she will own a car like that. Her cousin laughs.

Many, many years later, after securing her first proper job at Group 5, Bridget Masango drives from Johannesburg to her mother’s homestead situated on “tribal” land in a navy car. She pulls up to the cluster of homes. Her cousin runs out and bursts into tears. The young girl’s dream has been realised. All on her own. But Masango will tell you she did not do it alone. It was God – God and the kindness of countless strangers who got her where she is today. DM

Become an Insider

Become an Insider