Maverick Life, South Africa

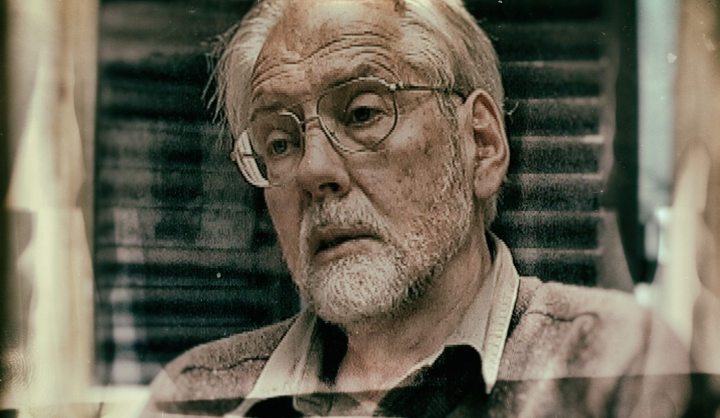

Dying with Dignity: Karel Schoeman – a private life, a public death

In life, one of South Africa’s most prolific and celebrated historians, novelists and translators, Karel Schoeman, was notoriously hermitic, shunning most contact with the outside world. Schoeman, who worked as an archivist at the National Research Library before he retired, led a rich inner life, populated by little-known voices and characters of South African history whom he honoured in his delicate, accomplished writings. But Schoeman’s self delivery – or suicide – on Monday at the age of 77 has once again opened the debate about the legal right to die with dignity in South Africa. He wanted it that way. By MARIANNE THAMM.

Accepting the Alan Paton Award for non-fiction in 2014, journalist, commentator and author Max du Preez remarked that it was really Karel Schoeman who should have been the recipient of the award. Schoeman, said Du Preez, was one of his “all time heroes” who had influenced Du Preez’s thinking.

“I only came tonight because I thought I was going to meet Karel Schoeman. And then he didn’t come! Which has kind of destroyed my night. But Karel Schoeman is one of my all-time heroes. He’s influenced my thinking, I envy his knowledge and his commitment. This really should have gone to him. He’s a spectacular guy. I’m sorry to miss him once again. He doesn’t return my phone calls or my e-mails. For 25 years.”

That was Schoeman.

Prolific and versatile, Karel Schoeman wrote 19 collections of prose and some 46 works of non-fiction, biography, historical writing, autobiography and travel, covering 300 years of South African history and establishing a unique and engaging style of interpreting this past. He wrote, like some of his characters, for those who could not.

Schoeman’s literary landscape was vast and wide. He wrote about the history of Bloemfontein, Scotland, biographies of Olive Schreiner, Irma Stern as well as penning historical masterpieces including titles such as The Griqua Captaincy of Philippolis, Early Slavery at the Cape of Good Hope and Seven Khoi Lives: Cape Biographies of the Seventeenth Century.

His works of fiction, while often engaging with the past and history, were also about the inner journey of the protagonists within a specific geographical and historical landscape.

Years ago, when he still worked as an archivist at the National Research Library in Cape Town, Schoeman, with his full head of grey hair and goatee beard, could often be spotted purposefully striding to work through the Company’s Garden. His “office” was in the basement of the library, a wondrous treasure trove of documents and material that would form the essence of so many of his books, all of which were meticulously researched.

Schoeman was a maverick, a man outside of his time. After matriculating from Paarl Boy’s High in 1956 he obtained a BA degree in languages from the University of the Free State. Then, in 1961, Schoeman joined the Franciscan Order in Ireland as novice for the priesthood, but returned to Bloemfontein to obtain a Higher Diploma in Library Studies in 1983. Prior to this he had worked as a nurse in Glasgow and a librarian in Amsterdam.

Perhaps the younger Schoeman, in seeking the priesthood, had hoped to inhabit the hermitic and ascetic life he would later fashion for himself back in South Africa.

Schoeman at once belonged in the world but was not of it. If he could have asked a genie for one superpower it probably would have been the ability to render himself physically invisible apart from the manifestation of his writings.

And on Monday, May 1, Schoeman did just that shortly after delivering, by e-mail, the closing chapter of his final manuscript to his publishers with “Final Greetings (Laaste Groete)” in the subject field. The book is expected to be published in September.

Schoeman, who was born in Trompsburg in the Free State in 1939, died in the Noorderbloem retirement home in Bloemfontein. He was 77 years old. In a letter to his lawyer, composed on 27 April and simply titled “Statement”, Schoeman set out how he had long planned to end his life before he grew too old, as well as his thoughts on his right to die with dignity in South Africa. He noted that in contemplating ending his own life he had been surprised at the extent of the moral and practical support he had received.

Schoeman concludes the letter with, “My own impression is that this is an apt time to widely and openly discuss in South Africa the question of self delivery. Should I succeed in my current attempt, those involved are, as far as I am concerned, totally free to discuss this with the outside world. I hope that my death will contribute to a more general discussion than currently exists of the real problems of ageing as well as the question of self delivery. I also hope that it will help to amend current South African law with regard to self delivery. This is enough.”

In his farewell, Schoeman dispassionately writes that the decision to end one’s life was a “highly personal” issue that he would not “blindly” recommend. He explains that current South African law made provision for a Living Will which directed medical personnel not to intervene in a life-threatening situation.

Another method of ending his life, wrote Schoeman, would be to fast – declining food and water – and in so doing starve to death.

“This is the method that I, in the absence of a dignified alternative, originally settled on for myself. It is a protracted way of dying and not necessarily without discomfort and pain, apart from the burden it places on those who are prepared to offer support during the process. Yet this is at least a dignified way to end life, which cannot be said for the alternative methods that are available in the current circumstances in South Africa.”

The writer, who was single – although the Afrikaans description “alleenlopened” (walking alone) is much more apt – begins his letter by expressing his wish not to grow old and revealing that he had decided years ago “to end my life, or at least try and end my life, timeously”.

He reveals that an attempt to end his life at the age of 75 had failed and says, “I am 77 and it has become necessary now to tackle this task while I still have mobility, physical freedom and the mental clarity to make a meaningful decision in this regard and to execute it effectively.”

He adds that he had become aware over the past two years that the research and writing that had kept him occupied for so long had become a burden and that he had “with a certain amount of relief” begun to distance himself from this. During this process, says Schoeman, he had grown acutely aware of his physical and spiritual decline.

“What lies ahead for me, in terms of my humanity, and in all likelihood, is an increasing condition of helplessness and dependence during which I will become a burden to myself and others.”

It is not exactly clear how Schoeman died – whether he did in fact opt to starve himself to death – or elected to use another method. An autopsy is still due to be performed.

Schoeman’s death and his plea for the debate about death with dignity comes at a time when Dignity SA is gearing up to continue to challenge legislation in South Africa with regard to assisted suicide and the right to die with dignity.

In December 2016 the Supreme Court of Appeal overturned a 2015 High Court Ruling granting the terminally ill lawyer, Robin Stransham-Ford, the right to die with dignity by way of euthanasia. The overturning of the ruling upholds the country’s current laws rendering assisted suicide a criminal offence.

Stransham-Ford, who had cancer, died a few hours before the High Court ruling and the SCA ruled that the claim ceased to exist once Stransham-Ford had died before the order could be granted, the Department of Justice has maintained. The ministry added that the SCA had held that this had been an inappropriate case in which to develop “the common law of murder and culpable homicide”.

Professor Sean Davison, chair of DignitySA, has continued to lobby for the amendment of South African law with regard to the right to die with dignity.

In 2015 Davison posted on Facebook that he had spoken at a medical symposium in Cape Town attended by over 100 medical doctors.

“The title of my presentation was ‘The right to die with dignity’. I was expecting a cool response from the audience since it is a pattern throughout the world that doctors are reticent on the subject of assisted dying. To my surprise, when I polled the audience, 80% were in favour of changing the law to allow for assisted dying for the terminally ill. However, even more surprising, after I had presented my talk, was that at least 50% of the doctors supported assisted dying for those with ‘unbearable suffering’. Having doctors supporting our campaign for a law change is crucial to its success – I am now confident that we can get them on board throughout the country.”

Schoeman provided through his fiction some of these existential issues that he himself finally had to face and which he hoped would contribute to a more urgent endeavour to provide those who wish to do so the right to end their life with dignity.

His legacy exists not only in the fiction or grand historical accounts he wrote, but also in the reanimation of individuals, both well-known and obscure, whose forgotten lives he encountered in the archives and who he thrust back into public view. Schoeman is one of the country’s most important historians whose work exhorts us to take heed of the past.

“The past is another country; where is the road leading there?” writes Schoeman in one of his early novels, This Life.

He will most certainly be remembered for his parting gift, that of prompting us to engage with urgency the universal matter of the right to die with dignity. DM

Original Photo: Karel Schoeman (Netwerk24)

Read more:

- For a full list of Schoeman’s published titles and awards see here:

- Listen to a podcast of Professor Willie Burger discussing Schoeman’s significance here

Become an Insider

Become an Insider