South Africa

Op-Ed: Replacing Zuma does not in itself rebuild democracy

There is a widespread assumption that the removal of President Jacob Zuma can set in motion a process whereby the ANC returns to its “true self” and that this will rescue South African democracy. There is no “true ANC” to which there can be a return and there is no certainty that it can play a meaningful role in restoring democratic rule in the country. There needs to be a broader national discussion on the problems of South Africa and possible routes towards rebuilding our democracy. By RAYMOND SUTTNER.

First published by polity.org.za

In the wake of the disruption of Workers’ Day rallies, the need to prepare for a post-Zuma era becomes more urgent. Most of the efforts to dislodge President Jacob Zuma do not operate with a paradigm for change. There is a widespread assumption that removing Zuma and replacing him with someone who is not a stand in for Zuma, that is, not a person from the “Zuma camp”, will deliver the freedom we ought to enjoy.

The assumption – in most or many cases – appears to be that the ANC is an organisation that needs to be returned to its pristine state, what it was or is assumed to have been before Zuma became president. Then, it is claimed, the organisation will take its place in South African life where it (again) becomes the centre and guarantee of democratic life and opens possibilities for realising the potential of each and every one of us.

What the ANC was before Zuma is not part of any serious examination in calls to return the ANC to what it ought to be. It should be part of such enquiries, in the light of Zuma deriving from the loins of the ANC itself. This is something which all of us who were or are part of the ANC ought to be asking ourselves. What is it that made it possible for such a person to rise to leadership and continue to enjoy support and collaboration in a range of types of wrongdoing? I am one of those who bear some responsibility because I was specifically charged as ANC head of political education (1990-4), after the unbanning of the ANC, with training members and building understandings of the principles of the ANC – in complex and changing conditions. Many who worked with me or were trained then have become leaders today. I have to ask, like others, what responsibility we may bear.

Instead of such introspection Zuma’s rule is, seen as an aberration, something that radically departs from what has hitherto been known in ANC leadership and consequently he is seen as holding the organisation captive. His removal is depicted as setting the ANC on a course towards “what it is meant to be”. Under the “reborn”, “restored” ANC the country is then expected to become what it can be and to realise all its potential.

Clearly some of this campaigning for Zuma to be removed converges with the assumption that the resolution of current problems can simply be achieved by replacing Zuma with Cyril Ramaphosa. Thus one of the ANC stalwarts, who has appeared prominently in television footage, privately and without explanation sent me a statement of the 101 stalwarts and again without any elaboration also a campaigning leaflet for CR17 (Cyril Ramaphosa2017). The leaflet contains some vague statements of what Ramaphosa represents. It, understandably, lacked any vision, understandably, because Ramaphosa has not presented any.

We need to probe the rise of Zuma further. I do not question that some people made bona fide errors in supporting Jacob Zuma, that they understood his election as freeing the ANC, the tripartite alliance and the country from what they saw or depicted as the grip of a ruthless and centralised leadership of Thabo Mbeki, where democracy could not flourish. Zuma being at the helm was supposed to signify leadership by a person who derived from the poor and had an understanding of the popular. Under his leadership, it was claimed democracy would again revive and develop.

When I first met Jacob Zuma in Lusaka in 1989 I was impressed with him and I thought it was only in the ANC and SACP that it was possible that someone with a limited formal education could become a leading figure. I did not know much about Zuma but read into what I saw, qualities that were probably not there, because I supported the idea of leadership being developed without necessarily passing through conventional, relatively elite processes. I had in mind two of the giants of the ANC and SACP, Moses Kotane, who had no formal education and Walter Sisulu, whose formal education was very limited.

But even then, looking back, there were warning signals that I did not understand at the time. I had left the country illegally, defying my house arrest under the State of Emergency and I was staying in an “underground” house in Lusaka. There was a telephone in the house and almost every evening Zuma, who was ANC head of intelligence would arrive and use it for a very long time. I have come to know more about how intelligence operates subsequently. What I understand is that if one is using a “safe” telephone (if there is such a thing) in a vulnerable city like Lusaka in 1989 one uses it very briefly and purely to communicate a limited message that is necessary for what ought to have been a very sensitive matter, which could only at that moment be communicated by telephone. If it were not used that way what was relatively safe would become vulnerable. It should be recalled that it would be unusual to use a telephone in the light of a range of other clandestine methods of communication that were in use and generally safe.

Zuma would instead conduct long conversations, while laughing continuously. Now laughing could be part of the way in which one covers what one is in fact doing but it does seem a bit far-fetched that this highly sensitive telephone was used for a long time and for what seemed to be social calls. In short, this was a sign of abuse, though I did not understand that at the time.

If I am correct in interpreting this as a misuse of a valuable and sensitive resource it was presumably a characteristic of Zuma of which others were aware. Indeed I have heard that comrades knew of many of the practices currently identified with Zuma today before they supported his rise to the presidency.

If Zuma is removed (I am not sure who will do that, at this point in time) and we want to rectify what is wrong with the country we cannot assume it will be the ANC that is able to set in motion processes that can ensure that the country enters a course where democratic debate, democratic processes and transformation of peoples’ lives can ensue. We are talking not just about the avarice of an individual and his allies but what has become systemic undermining of the law and the constitution, the procedurally required modes of functioning of the state and state owned enterprises (SOEs), the resort to violence against many who protest against often unlawful acts of the present ANC-led government at various levels.

Many people are heaping praise on the judiciary – justifiably, but basically for doing its job. It acts as it does because it has become a pattern that what is required from the state and SOEs are undermined by officials, boards and ministers. Many of the ministers concerned, continue to hold their jobs, notably the Minister of Social Development, despite a damning Constitutional Court judgment. The courts stand out – institutionally – in an environment where institutions have been hollowed our or are dysfunctional or abused.

Are there elements within the ANC that have a demonstrable capacity and appetite for uprooting the problems that now confront the country, when the organisation itself is generally at the centre of these? We must remember that Zuma is simply doing wrong at the top. There are Zuma prototypes operating on a smaller scale, to be sure, but engaged in similar activities at different levels of society. Some of this preceded his rise to power.

It is important to restate that the objective of any campaign for democracy cannot be simply to remove the current president and replace him with another person, whether Cyril Ramaphosa or anyone else, who are seen as automatically delivering us from the woes of the present. In reality, this messianic approach cannot be relied on to work.

The ANC itself cannot be a “no go” area in terms of understanding why we experience the problems of the present and we cannot assume that “restoration” of the ANC to what is assumed to be its former greatness (if it means simply removing Zuma) resolves the broader damage that has been done.

One of the reasons why it may seem possible to treat the problems we confront, as having simple answers is that there is an absence of serious debate.

Such debate must entail arguing over the character of our democracy, how it is that it was possible for a type of coup to be perpetrated, and a situation to arise where a leader is free to act unconstitutionally and with a high degree of impunity, based on endorsement of the majority enjoyed by the ANC in parliament. We need to ask how it is that individuals, some of whom used to be very brave and ethical, have acted to shield such action in a manner that means there is often no remedy when ethics, obligations and constitutional provisions are violated. MPs and leadership of the ANC have supported the president that we the citizens apparently have no simple way of removing.

If, say, Ramaphosa is elected to replace Zuma, though his election may be much more difficult than many imagine, where does that put us? What ideas have Ramaphosa or his supporters advanced other than that it will not be what Zuma does, in other words, end corruption, patronage and dirty deals. It is very unclear how all that will be achieved… is there a broader democratic and transformational vision, within which this is embraced?

In aiming to restore democratic rule we need to be prepared to initiate a broad national discussion where everything comes under scrutiny. Some people believe changing the electoral system would solve most of our problems. I do not buy that, but it needs to be part of any national discussion.

I do believe that we need to ask ourselves what it signifies to have the population in the streets, in massive protests calling on the president to resign. In one sense it means that the institutions established by the constitution are not functioning adequately and that people take to the streets to directly demonstrate the power that is supposed to be exercised on their behalf by the elected representatives.

But this points to a broader and significant discussion we need to have. That relates to the place of the popular, of ordinary people in the functioning of our democracy. Is it only in abnormal or drastic situations that people should be involved in politics and on the streets? Are the people only present in our democracy when they vote or protest? For the rest of the time is it to be left to the professional politicians in parliament and other state officials?

We need to revisit our understanding of democracy, in a situation where popular democracy and to a large extent, also participatory democracy have been more or less replaced by representative democracy.

This is part of a larger debate that never took place, because alternative traditions to that of representative democracy have simply been displaced.

Representative democracy assumes the good faith of representatives, that they will act with integrity in representing the interests of the people who elect them. They are entrusted with that obligation. We know that our representatives have repeatedly violated that trust.

There is some space for participatory democracy under the current constitutional order, as in the openings for public participation over legislation in many instances. It is sometimes unsatisfactory and also violated, as in the conduct of procurement in the nuclear deal, as recently found by the Western Cape High Court.

But there is also a tradition of direct, popular democracy that many who participated in the struggles of the 1980s envisaged as a continuing feature of South African democracy. This was not seen as oppositional, in every case, though it could sometimes entail that. It was mainly conceived as a way of people taking control of their own lives, sometimes in collaboration with the state and sometimes independently. The time may be ripe to revisit that tradition, within a broader debate on what we expect and want from our democracy. DM

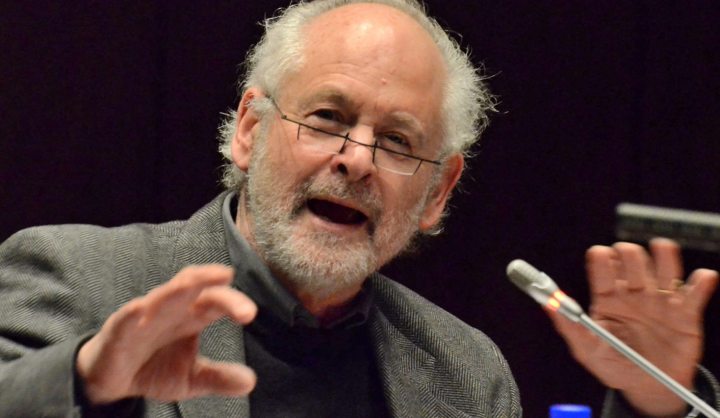

Photo of Raymond Suttner by Ivor Markman.

Raymond Suttner is a scholar and political analyst. Currently he is a Part-time Professor attached to Rhodes University and an Emeritus Professor at Unisa. He served lengthy periods in prison and house arrest for underground and public anti-apartheid activities. His prison memoir Inside Apartheid’s prison will be reissued with a new introduction covering his more recent “life outside the ANC” and will be published by Jacana Media late in May. He blogs at raymondsuttner.com and his Twitter handle is @raymondsuttner

Become an Insider

Become an Insider