Maverick Life, World

Review: The Chocolate Case, the Netherlands’ answer to child slavery

As South Africa celebrates Human Rights Day, it’s worth taking a look at The Chocolate Case, a new documentary detailing the devastating impact of child slavery in the chocolate industry. By MARELISE VAN DER MERWE.

Do you like chocolate? You might like it a little less after watching The Chocolate Case. The film, which premieres in South Africa at the Eco Film Festival, follows the journey of three Dutch journalists on a mission to blow open slavery and child labour in the chocolate industry.

Directed by Benthe Forrer, the film follows the journalists – Teun van de Keuken, Roland Duong and Maurice Dekkers – in their attempts to get answers from multinational food producers. The initial investigation, which kicked off in 2003, is both funny and sobering; the journalists first simply want to investigate the origins of various popular supermarket products. Their multiple failures to get answers to even the most straightforward queries are farcical and eye-opening in equal measure. Until the day they begin questioning the origins of chocolate and disappear down a rabbit hole of forced labour and child slavery. Needless to say, efforts to get answers are met with hostility.

Van de Keuken opts for a most unexpected approach: barring any co-operation from the companies he has attempted to contact, he attempts to get himself prosecuted for purchasing and consuming goods produced through child labour and slavery.

The police, on his first attempt, wish him a pleasant day.

Watch: The Chocolate Case Trailer

Slavery in the chocolate industry has gained some prominence over the last 15 years. The CNN Freedom Project, for instance, provides sustained coverage and support. In 2015, a lawsuit filed against Hershey, Mars and Nestlé accused the companies of false advertising for refusing to disclose that they used child labour. Earlier this year, Forbes reported that the long-running case against Nestlé had been thrown out for the second time.

Fortune reports that despite the expectation that exposure would drive slavery down after its first exposure, it has actually increased over the last decade, particularly in West Africa. Child labour has grown by some 21%. Children as young as six are forced into grim conditions.

Enter Van de Keuken, Duong and Dekkers. The film, which was finally released in 2016, takes an in-depth and distressing look at the stories of numerous insiders. Sources tell the trio that children are recruited from poor families and promised an education, but are instead taken to work in plantations.

“We can all close our eyes and say ‘it’s not my fault’,” says Duong. “But if you eat that product, you contribute to it.”

When the journalists contact Nestlé’s headquarters in Switzerland, the head of PR responds that indeed there are many children working on the plantations, but calling them slaves is a matter of interpretation.

“It is indeed a fact that many children – not slaves, huh – that is a total interpretation. For a poor farmer in Africa, often the help that he gets from his children is vital to maintain the standard of living of the family. What’s wrong with that?”

Later he adds: “Let’s face it. Slavery exists. Because they are so desperately poor.”

Upon being asked whether their ongoing poverty has anything to do with the low pay they receive from Nestlé, the respondent rings off, saying he will discuss it further when the journalist is willing to be “rational”.

The Chocolate Case, it should be noted, is first and foremost a cracking good story. It exposes an issue that deserves never to be forgotten. But it is not just another documentary: the matter is in the hands of masterful narrators. It takes a remarkable storyteller to make one chuckle when the subject is child labour, but they manage it, with smatterings of farcical humour dotted throughout. Michiel Pestman, Van de Keuken’s lawyer, reads earnestly: “I hereby report a crime committed by [my client] in Amsterdam on 12 February 2004. That day my client was guilty of fencing, by eating chocolate, made from cocoa produced by the use of forced labour.

“I understand that the crime concerned Smarties, After Eight, Bounty, Mars, Twix…” He narrates the list excruciatingly slowly. “…M&M, Milka, Toblerone, Cote d’Or, Verkade and – ” he gives a final disapproving nod – “Ritter sport bars.” He finishes with a solemn entreaty to give an answer regarding his client’s fate as soon as possible, as the uncertainty is understandably worrisome.

The strategy was dual: to make for more interesting news coverage, certainly, but also to avoid accusing the manufacturers directly. Had they done the latter, admits Van de Keuken, they’d have been faced with a battalion of lawyers within a week “and they’d have wiped the floor with us”.

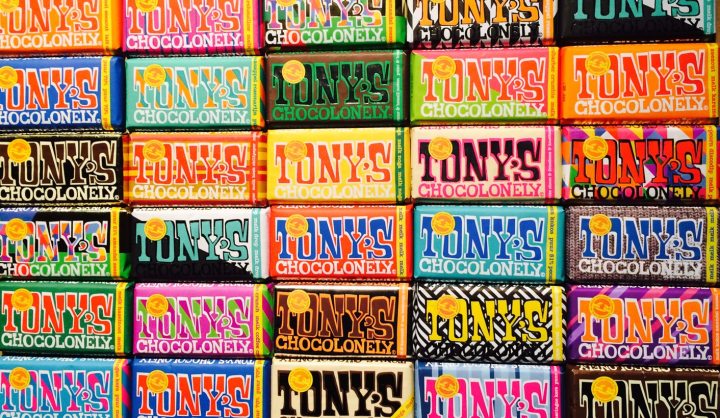

Spoilers aside, it’s a long and convoluted journey through the justice system. But there’s something else that makes this story unique: along the way, the journalists decide they cannot but provide an alternative to unethically produced chocolate, and set up their own chocolate company. Today, Tony’s Chocolonely is the largest producer of chocolate in the Netherlands, having surpassed Nestlé.

“I think we have managed to do a lot in the past 11 years — by finding small corporations in Ivory Coast and Ghana, and having our own guy permanently there, or going there 15 times a year, to build a close relationship with those farmers,” Dekker said in 2016, following the release of the film. “There is a lot of work to do. The whole system needs to change, including big corporations like Nestlé. Now, we have also become quite big, so we can talk with the big corporations and be taken seriously.”

Tony’s Chocolonely, as well as the rise of Fair Trade labels, has played a part in underlining the ongoing complicity of non-compliant organisations, he adds. “Us becoming part of the chocolate industry has also changed things, because now the other companies have to accept our way as an alternative. We have proved that it is possible to do things in a non-exploitative way. In a way it means an admission of guilt from the other companies.” DM

The Chocolate Case is screening at the Eco Film Festival on Friday 24 March and Sunday 26 March. View the full programme here. Daily Maverick is media partner to the Eco Film Festival.

Become an Insider

Become an Insider