Africa

Governance in Africa: What do the numbers tell us?

Measurable good governance. That is what African countries need. By LYAL WHITE and ADRIAN KITIMBO.

Africa’s track record of governance since independence is, at best, mixed. Despite the moderate socio-economic and political progress made since independence, only a few countries have improved their performance relative to those in other parts of the world, and these are mostly recent developments confined to some of the smallest countries on the continent.

According to most measures, Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) remains the least competitive region on the planet, stuck between the ebbs and flows of commodity cycles and global paradigm shifts. Despite enjoying its best decade of economic growth on record from 2002 to 2012, African countries continue to populate the bottom rungs of the 2016 Human Development Index (HDI), which measures key aspects of human progress such as life expectancy, per capita income and education. One in two Africans still live in extreme poverty, and Africa has overtaken Latin America as the most unequal region in the world.

Countless arguments have tried to explain Africa’s lacklustre development record and perennial underperformance on various scores and indices. It was the British economist, Richard M. Auty, who coined the term “resource curse”, linking the endowment of natural resources such as oil and minerals, as we see in many African countries, to slow development, corruption and authoritarianism.

Others have blamed the continent’s underdevelopment on geography, diseases and the legacy of colonialism. In more recent years the development debate has become a sparring contest between two opposing camps: One side, championed by the economist Jeffrey Sachs and celebrities like Bono, advocate for more aid. Others, like famed Zambian economist, Dambisa Moyo, insist that development aid is part of a bigger problem, crowding out productive capital and undermining good governance in Africa.

Regardless of which side of the ideological debate or angle of the argument taken, at the heart of it, poor governance has undermined Africa’s socio-economic progress. By falling short on their key obligations, which US political scientist Robert Rotberg calls “political goods”, African governments fail to deliver on security, political participation, the rule of law, and ultimately sustainable economic opportunity and human development.

And through the grand debates, a mixed record of results and a sketchy collection of data and facts, Africa’s overall governance is difficult to measure. Application for policymakers and practitioners seeking an empirical basis for comprehensive competitive performance is even trickier. But new tools with a decent record of annual averages dating back more than a decade can provide better insights through a composite collection mixed with practical observations and experiences on the ground. The Ibrahim Index of African Governance (IIAG) and the GIBS Dynamic Market Index (DMI) are two such measures.

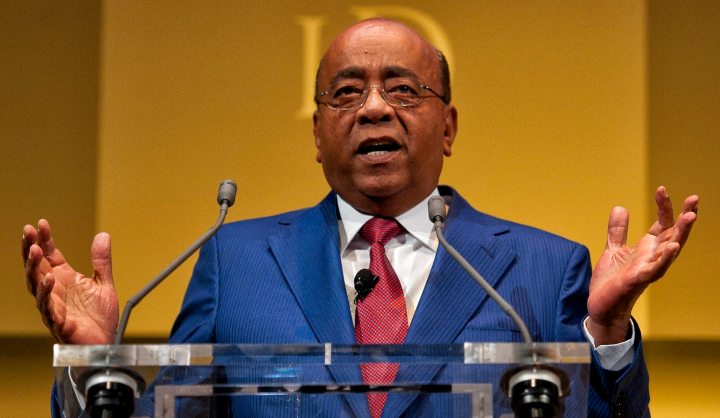

The IIAG is perhaps one of the most comprehensive and robust tools for gauging governance performance in Africa. Funded by the Sudanese-British billionaire Mo Ibrahim, and first published in 2007, the index measures the quality of governance across 54 African countries.

In its most recent iteration, the 2016 IIAG found that over the last 10 years Africa has experienced a very slight overall improvement in governance. Notable improvements were in the areas of human rights, human development and sustainable economic opportunity. But a concerning trend saw safety and the rule of law decline sharply over this period. Up to 33 of the 54 African countries measured experienced a decline in these categories, questioning the ability of African states to meet the fundamental needs of any society.

The top three performers on the IIAG were Mauritius, Botswana and Cape Verde. Interestingly, this is consistent with other indices that measure economic performance. Meanwhile Sudan, South Sudan and Somalia took the unenviable bottom spots. Some of the most improved countries measured include Côte d’Ivoire, Zimbabwe and Rwanda. South Africa, the continent’s most industrialised country, saw an overall deterioration, with its scores plummeting especially in the areas of safety and rule of law.

The IIAG’s results tend to echo those of the DMI 2016. The DMI measures and compares the institutional performance of 144 countries around the world, using averages between 2007 and 2014. While the DMI is a global study and not just Africa-focused, some of its conceptual pillars do overlap with the variables that inform the IIAG. The DMI pillars include: Open and Connected, Red Tape, Socio-Political Stability, Justice System, Macroeconomic Management and Human Capital. In step with the IIAG, the DMI’s findings demonstrate an overall (albeit small) improvement in the quality of institutions towards good governance. But there was a significant drop-off in performance since 2012 and a significant number of African countries still lag behind their global peers.

Most African countries are categorised as “catch-up” markets in the 2016 GIBS DMI. These are predominantly low-income countries with poor institutional foundations but have demonstrated impressive structural improvements since 2007. Similar to the IIAG findings, Rwanda and Côte d’Ivoire are among the fastest improvers on the DMI, while the Central African Republic (CAR), off an already low base in 2007, registered one of the sharpest declines in governance on both indices.

Botswana and Mauritius, which are the top performers on the IIAG, are also the only two “dynamic” markets on the GIBS DMI. Dynamic Markets are characterised by a relatively high level of dynamism in the 2007 base year. More important, they have maintained and often improved on a number of institutional measures over the period of analysis. Meanwhile, in tandem with the IIAG, South Africa performs rather poorly on the DMI despite its relatively high base level of institutions in 2007, registering no improvement during the period of measure. South Africa’s poor performance has been plainly evident in the uncertain political and economic environment that has hamstrung the country during the last few years.

There are some notable differences in the results of the two indices. For example, East African powerhouses Kenya and Ethiopia were among the fastest improvers on the IIAG in the last 10 years. But both countries are categorised as “adynamic” on their DMI performance. This was largely as a result of inadequate progress in Ethiopia’s justice system along with a lack of open and connectedness, while Kenya suffered a serious setback around recent insecurity, political instability and social violence at the end of 2007, which had a lasting impact on the data. Simply, while both indices often have broadly similar results, they do not necessarily employ the same methodologies, and are thus not identical in their findings – a useful insight for composite measures and granular details needed in analysing the African context.

An interesting finding, albeit a broad correlation, is that between economic performance and the results from the two indices. Those countries that recorded an improvement in governance on both the IIAG and the DMI over the past 10 years are now some of the best economic performers, with either the highest growth rates or sustained levels of healthy growth. Rwanda and Côte d’Ivoire are such examples, growing at an average upwards of 6% over the last five years, and are increasingly two of the most competitive countries in Africa. Both countries are among a handful of SSA economies to appear in the top 100 on the World Economic Forum’s 2016 Global Competitiveness Index. This does suggest an important correlation between good governance and economic performance, where improved governance will lead to economic progress.

At a time when Africa seems to be caught in a perfect storm comprising the world’s lowest levels of governance and productivity, alongside the highest rate of inequality globally, individual countries need to get on track with a simple solution that will address these challenges and deliver growth and development. Measurable good governance is that solution. DM

Prof Lyal White is the director of the Centre for Dynamic Markets at GIBS, and Adrian Kitimbo is a senior researcher for the Centre.

Photo: Mo Ibrahim, Founder of Celtel and Satya Capital, delivers a speech at the Institute of Directors Convention at the Royal Albert Hall, Central London, Britain, 03 October 2014. EPA/WILL OLIVER

Become an Insider

Become an Insider