Maverick Life, South Africa

Abortion, 20 years on: Still contested, still needed

This week marks the 20th anniversary of South Africa’s Choice on Termination of Pregnancy Act, one of the world’s most liberal abortion laws. As a new report shows, though, the distance between what the law envisages and what is happening in reality is wide – to the point where government may be in violation of certain international human rights instruments. By REBECCA DAVIS.

Tuesday, February 1 was what anti-abortion campaigners call “The National Day of Repentance”. The date is considered significant because it was on February 1, 1997 that South Africa implemented the Choice on Termination of Pregnancy Act (CTOPA), allowing abortion on demand till the 12th week and with certain conditions till the 20th week.

It’s a dark day for those who would like to see abortion done away with, despite the fact that the law is estimated to have reduced abortion-related deaths and injuries by 90%. But the anniversary also provides scant opportunity for celebration among those in favour of reproductive rights, due to the ongoing failure to implement the legislation as envisaged.

An Amnesty International report released to mark the 20th anniversary of the CTOPA states, in summary, that abortion access is still a struggle for South Africa’s girls and women. Apart from anything else, this is problematic because high levels of sexual violence mean that abortion is needed as much as ever.

The Department of Health’s own figures show that only 264 of 505 designated facilities are actually providing the abortions they are supposed to. Just less than 50% are not. The major issue here, Amnesty suggests, is the refusal of doctors and nurses to perform abortions; or as it’s often known, “conscientious objection”.

This is a constitutional right on the part of healthcare providers, but only up to a point. Doctors and nurses cannot refuse to perform pre- or post-abortion care, and they cannot refuse to perform an abortion where there is an immediate risk to a woman’s health. They also cannot refuse to refer a woman to an alternative healthcare provider who will perform the requested abortion. The Amnesty report suggests that there is widespread ignorance and confusion over this within the South African healthcare system, and that without regulation – as is currently the case – conscientious objection “risks being invoked opportunistically”.

Report author Louise Carmody told the Daily Maverick: “Abortion-related stigma permeates the health system from the top down, which is why conscientious objections haven’t been properly dealt with.”

Mixed messages from the very top of the health system are not helping. Health minister Aaron Motsoaledi has repeatedly stated disapprovingly that young women use abortion as a form of contraception. Women’s health activists are adamant that this notion is not backed up by data.

Chair of the Sexual and Reproductive Justice Coalition Marion Stevens points out that Motsoaledi has previously spoken of women “committing” abortions – a strange choice of verb.

In an interview last year, Motsoaledi also referred to the provision of contraception to teens by parents as “the devil’s alternative” – i.e., undesirable but better than the other options of “HIV, teenage pregnancy and abortions”. The Health Minister has expressed similarly moralistic views on other topics. On the issue of euthanasia, Motsoaledi has been quoted as saying: “Only God can decide when a person dies.”

Stigma around abortion is not the only factor impeding its provision in South Africa, however. Access to services is also hampering its rollout. Amnesty notes that women in rural areas are “severely hampered” when seeking abortion by the large distances to healthcare facilities and the high costs of transport to reach them. This goes against the World Health Organisation’s exhortation to governments to ensure that safe abortion services are “within reach of the entire population”.

Information around abortion is also sorely lacking. Previous studies have found widespread confusion over whether abortion is legal in South Africa, and what the time frame is in which women may legally seek one. This is what helps to fuel illegal abortion services, long identified as a major health risk to women. Stevens estimates that more than 1,000 South African women die annually as a result of botched backstreet abortions.

Amnesty’s report concludes that the South African government has taken “noteworthy steps” towards protecting women’s reproductive rights, but that implementation of its progressive abortion legislation remains inadequate.

“In failing to regulate the practice of conscientious objection, and to ensure access to safe abortion information and services, South Africa has failed to fulfill obligations under the Maputo Protocol and other human rights treaties,” the report warns.

Asked if this carried the threat of legal action, Amnesty’s Carmody demurred: “Litigation isn’t something Amnesty would do, but we can support accountability for human rights in other ways.”

Stevens says that the picture painted by the Amnesty report may actually be slightly rosier than the reality. She says she frequently receives calls from people instructed by the Department of Health to visit a particular facility for an abortion, only to find that abortion services there have “gone offline” without the department’s knowledge. The funds for paying for medical abortions are also often unavailable.

“The problem is that there is poor political leadership in this regard,” Stevens says. She points out that the Department of Health’s website contains no information whatsoever as to how to legally and safely seek an abortion.

Stevens singles out Social Development Minister Bathabile Dlamini, currently under fire for the chaos surrounding social grants, for praise for having provided consistent and affirmative messaging around reproductive health. She also holds out hope for the influence of outgoing African Union head Nkosazana Dlamini-Zuma, who recently tweeted: “Sexual and reproductive rights should always be fought for.”

Anti-abortion protesters who demonstrated outside Parliament on Tuesday with a hearse as a prop now have powerful allies in the White House. The US embassy has said that no US agency is currently funding abortion services in South Africa. But the so-called Global Gag Rule could, for instance, prevent NGOs dealing with health issues like HIV from providing information to women about how to seek abortion.

On the 20th anniversary of legal abortion in South Africa, Stevens says that the climate towards abortion in this country has grown more hostile since the mid to late 1990s. “The Department of Health [used to have] co-ordination meetings, provincial task teams, and 66% of services were operational,” she says.

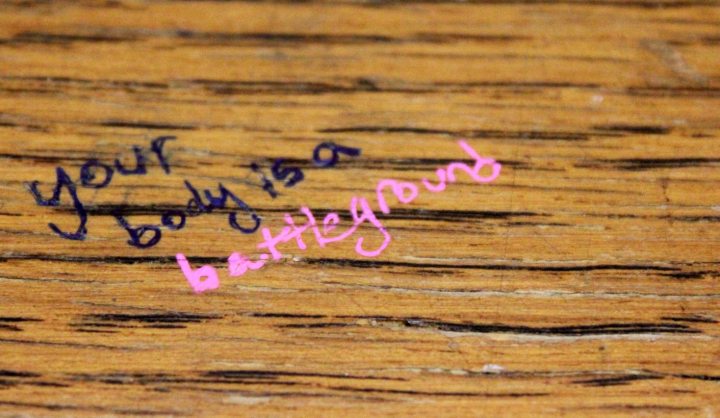

It is a stated mission of the South African anti-abortion lobby to “reduce the number of hospitals doing abortions”. Though they may have lost the legal war, implementation is a battle still being fought. DM

Read more:

- Sexual and reproductive rights should always be fought for, on Daily Maverick

Photo by Quinn Dombrowski via Flickr.

Become an Insider

Become an Insider