Africa, South Africa

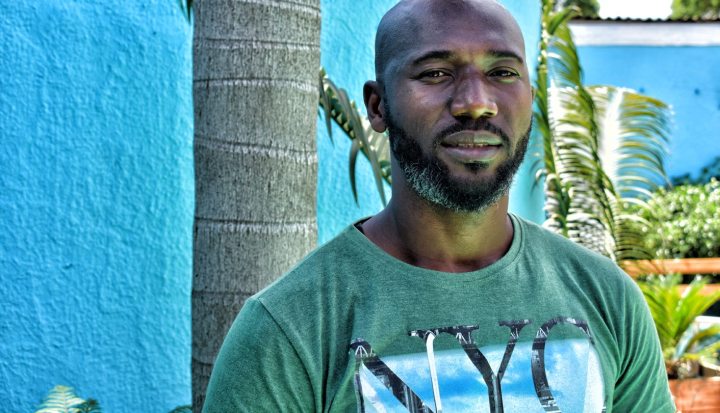

Portrait of an Immigrant: Cyprian Ikani

South Africa’s history has been indelibly shaped by immigrants, and its present is no different. In a new series, SIMON ALLISON speaks to a few of the men and women who have come to find a new life in this land. Cyprian Ikani is one of them. He describes why he left Nigeria, and his extraordinary trek to get here – a journey worthy of Nollywood.

After years of struggle, things are looking up for Cyprian Ikani. The 37-year-old Nigerian has earned his version of suburban bliss, finally: the elegant house on a tree-lined street in Yeoville – “not the dodgy side”, he clarifies – painted sky blue and decorated with wooden planters he made himself; his wife and a beautiful four-year-old boy, and a steady job with an NGO that advocates against xenophobia.

And, most important of all, the valid residence permit that allows him and his family to live in South Africa legally.

When he left Nigeria for the last time, in 2005, he never imagined ending up here. South Africa, to him, was little more than that place where white people hated on black people. “I remember watching TV, it always showed the struggle, and Mandela, and the famous musicians against apartheid. I said to myself, I can never in my life come to this country, even if someone pays the ticket for me, I won’t come,” he says.

But come he did, and the story of how he did so is so extraordinary that even a Nollywood scriptwriter would struggle to make it up.

We meet for lunch at a tavern in Yeoville, one that specialises in homely Nigerian cooking. It’s too early for jollof rice, the classic West African dish, so the chef serves up a steaming bowl of egusi soup instead, with a couple of Heinekens on the side.

Egusi soup is more like a stew, with pounded pumpkin seeds used to thicken the intensely savoury broth, and comes with a half-moon of pap. “This place makes proper Nigerian food. The closest I’ve found here to home. But we don’t eat pap in Nigeria,” Cyprian says. The dish should come with fufu, which is similar, but made from cassava instead of maize. As we eat – the pap rolled with one hand into tiny balls and dipped into the rich, dark yellow gravy – Cyprian explains how he ended up in Jo’burg.

Cyprian grew up in Nigeria’s deep south, in Delta State, and then in Lagos, looked after by his aunt after his father, a policeman, passed away. The family was big, and schooling sporadic, but he was resourceful and learned to look after himself. But he wanted more, and he knew that Nigeria was not the place to get it.

“It was only during the 1990s that Nigerians started travelling. They would go abroad, and they would come home large.”

Cyprian wanted to get large.

Aged 18, he hatched a plan with a close friend. They posed as porters and stowed away on a cargo ship en route to Belgium. For seven long days and nights, they hid in the hold and munched on the dry, doughy snacks that they had brought with them.

Finally, the ship arrived. They snuck out of the ship and took their first steps on European soil, except their destination was nothing like what they had been expecting. “It wasn’t Belgium. We’d actually stopped in Monrovia, in Liberia,” he says, smiling at the memory of his youthful ignorance. Dispirited, and broke, they had no choice but to stow away on another ship returning to Lagos.

A year passed before Cyprian decided to try again. He worked as a car washer at Lagos’s famous Berger car market, eventually saving enough money to try the overland route to Europe, up through the Sahel desert and across the Mediterranean. He didn’t get very far. He arrived in Niger, where the desert begins, and where robbers wielding long knives held him up and took all his money. Unable to continue the journey, he went back to Lagos, hitching rides and begging for food along the way.

Cyprian returned to his job at the car wash, but he wasn’t giving up yet. He decided that next time, he would do things properly, with a passport and a visa. After saving for two years, he got the passport, and then a visa for India. Now he just needed money for the flight ticket there. At his family home in Delta State, his mother put him in touch with a business associate who helped him out with the cash.

Disaster struck for a third time. A shared taxi turned out to be occupied by armed robbers, who drew their guns and shoved him out of the vehicle – minus his bags, the money, and his passport with the visa inside. India wasn’t happening any more.

Back to the car wash. It was five years later, in 2005, before Cyprian was ready to try again. He got a new passport, and had saved up enough money for a flight ticket. But he had no idea where to go. A visit to the Italian embassy proved fruitless – “they wanted all these documents that I didn’t have” – but he happened to pass the nearby Democratic Republic of Congo embassy on his way home. On a whim, he walked in.

It was around then that Cyprian’s luck began to change. In the embassy, another Nigerian helped him fill out the visa forms, and he received the visa just a few minutes later. He made it to the travel agent without getting robbed, and bought himself a ticket to Kinshasa, leaving within the week.

On the plane, heading towards a city he had barely heard of and knew not a soul in, Cyprian got chatting to a Nigerian businessman returning to Kinshasa. On arrival, the businessman introduced him to the Nigerian community, who rallied around the newcomer and helped him start a business trading in spare parts. For a while, life was good, but Cyprian was spooked by the Congo’s inherent potential for conflict. He wanted somewhere safe, and peaceful, where he could raise a family.

He hit the road again, heading south. In Zambia, he was put in jail by crooked cops who ignored the valid travel visa in his passport, and had to bribe his way out. By then, he had learned to keep his money safe, hidden in, rather than on, his person. In Mozambique, he hiked over mountains and was chased by soldiers who took from him whatever they could, but were happy to point him in the direction of the South African border.

Eventually, miraculously, Cyprian arrived at the MTN taxi rank in Johannesburg’s CBD. It was 10 at night. He knew no one, and was out of money. Someone told him to go to a bar down the road, “where the other Nigerians are”.

Once again, the Nigerian expat community rallied around him, although this time things were not quite as straightforward. The man who offered him a place to stay that night turned out to be a drug dealer, and recruited Cyprian into the business. But that wasn’t the life that Cyprian had dreamed of, and he quickly tired of living in fear of police raids.

He got clean. He took the money he earned and started selling cellphones. Business was tough, but rewarding.

After all these years, and borders, and setbacks, Cyprian was finally living large.

Cyprian works now for the African Diaspora Forum, a civil society group established by Johannesburg’s migrant community in the wake of the 2008 xenophobic violence. He’s thinking about moving to Sandton. He has not been home for 12 years. But even though things have worked out for him, eventually, he still wishes he had not had to leave in the first place.

“I want to live in an Africa where we don’t have to run to another man’s country to make a living. I want job opportunities, good healthcare, good education at home. We need to make it so that when our people travel, it’s only for a holiday.” DM

Photo: Cyprian Ikani (Simon Allison)

Become an Insider

Become an Insider