South Africa

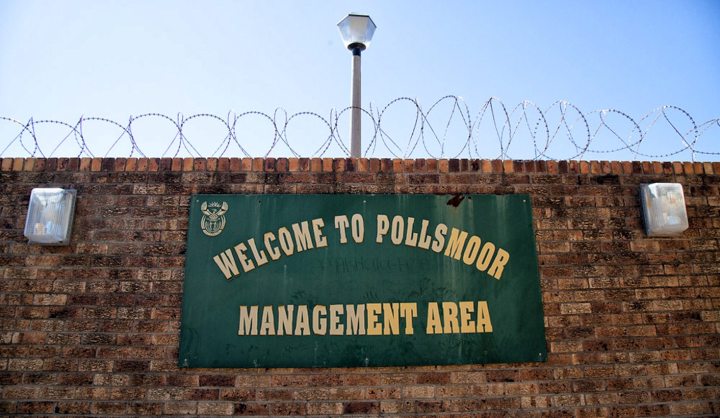

Op-Ed: After the Pollsmoor judgment – recognising repeated failures in our criminal justice system

Pollsmoor is not alone in the problems it has with inhumane conditions and overcrowding. Most remand detention facilities (RDFs) in the Western Cape already operate above 120% occupancy. And nothing indicates that the situation is vastly different elsewhere in the country. By GWEN DEREYMAEKER.

On December 5, 2016, the Western Cape High Court declared that the conditions of detention at the Pollsmoor remand detention facility (Pollsmoor RDF) were unconstitutional. The government has until December 21, 2016 to show why the court should not order it to reduce the prison population at Pollsmoor RDF to 120% of approved accommodation, from its current approximate level of 250%. Furthermore, the government must submit a comprehensive plan to the court by January 31, 2017, including time frames for implementation, aimed at addressing and remedying the deficiencies that led to the inhumane conditions of detention at Pollsmoor RDF.

The problem is not unique to Pollsmoor. Most remand detention facilities (RDFs) in the Western Cape already operate above 120% occupancy. For example, in October 2016, Caledon RDF stood at 231% occupancy and Malmesbury RDF at 271%. For the government to comply with the High Court’s order (and based on detention figures from October 2016), it will have to find an additional 2,089 bed spaces near Cape Town by December 21, 2016, or release 2,089 remand detainees. The latter option will in no doubt cause a public outcry. However, 33 of the 43 prisons in the Western Cape are above 120% occupancy. Simply moving inmates from one overcrowded prison to another overcrowded one will only create another unconstitutional situation. Nothing indicates that the situation is vastly different elsewhere in the country, especially in RDFs around urban centres.

One option discussed during the Pollsmoor hearing was to detain people in police cells. However, the law only permits this in very limited circumstances and for up to seven days. Furthermore, Western Cape police cells do not have the capacity to detain all remand detainees currently held in RDFs with occupancy levels above 120%, without creating another unconstitutional situation. Also, the chances of SAPS agreeing to this are slim to non-existent. Therefore, detention in police cells is neither a sustainable nor a feasible solution.

Therefore, unless the government as a whole addresses the systemic causes of overcrowding, especially in RDFs (which hold people who are still on trial), follow-up litigation is predicted. The responsibility for overcrowding rests with government as a whole, and more specifically with the South African Police Service (SAPS), the National Prosecuting Authority (NPA), the courts and DCS.

Three reasons explain the high levels of overcrowding in RDFs.

First, SAPS arrests too many people who will never be sentenced. One of the SAPS performance indicators relies on the number of arrests executed, without assessing the appropriateness of many arrests. Research by CSPRI highlights that in 2015/16, SAPS arrested 1,638,466 people, but the NPA secured just under 300,000 convictions and about 200,000 alternative dispute resolutions. Because SAPS and the NPA report in different ways, and because not everyone who is arrested will be transferred to prison, these figures do not mean that over one-million people were wrongfully arrested or wrongfully detained, pending trial. However, the difference indicates that too many people are arrested by SAPS and will spend time in an RDF, only for the matter to be withdrawn or struck from the court roll. Their detention was therefore, in principle, unnecessary.

A second explanation is found in our bail legislation, which is strict and provides that those against whom there is sufficient prima facie evidence that they committed a serious crime are likely to tamper with evidence or interfere with witnesses, for example, will not be granted bail. However, the changes made to bail laws in the 1990s have made it much more difficult for people to be granted bail and to be granted bail quickly, even when accused of minor offences. CSPRI’s Jean Redpath has written about this situation, which she calls “unsustainable and unjust”. Issues include the fact that courts no longer hear bail hearings after hours; that protective measures surrounding the postponement of bail hearings have been lessened, and that a reverse onus is now placed on the accused to justify why he or she should be released on bail when charged with a serious crime. The latest NPA annual report indicates that courts only sit for just over three hours per day. Another issue highlighted by UCT academic Jameelah Omar is the affordability of bail, by which the mere fact of being poor likely excludes the accused from being granted bail or from being able to afford the bail amount set by the court.

Third, our laws do not provide for mechanisms that regularly review someone’s detention while on trial to verify whether the detention remains justified. Also, there are no limits to the length of remand detention, whereby the seriousness of the offence would determine the maximum length of such detention. The absence of these mechanisms results in innocent people sitting in detention for months, even for minor offences, without the police or the NPA being pressured into completing the trial swiftly. Former CSPRI researcher Clare Ballard, who was the instructing attorney in the Pollsmoor case, highlighted these challenges and recommended that custody time limits and mandatory automatic oversight of bail decisions be put in place.

As DCS often correctly points out, they are at the receiving end of a criminal justice system that simply produces too many remand detainees for too long. However, the Department of Justice and the Department of Correctional Services fall under the same Minister since 2014. Two years later, very little has resulted from this merger. Overcrowding at the level observed in most urban RDFs are an affront to human dignity and addressing it should have been a key priority for the new super-ministry.

It is further important to note that the government did not oppose the Pollsmoor application. It was not represented in court nor did it file a motion of compliance. At this stage, only the government knows that this is either because it knows the situation is unconstitutional and must be changed, or because it cares little about the conditions of detention in our prisons.

Where to from here?

First, the government could build more prisons, but that is expensive, time consuming and there is little evidence that it provides a long term solution. Also, for all inmates to be detained in prisons at 120% occupancy, the Western Cape alone would need two new prisons of the size of Pollsmoor.

Second, laws, policies and practices could be changed. Many academics and civil society organisations have often reflected on possible solutions, with which government could engage.

But, equally important, the police should stop arresting solely to meet their arrest targets, trials could be completed much faster, and the government could re-invest in long-term crime prevention strategies.

What we need are laws, policies and practices that truly reflect the values of our Constitution, not laws, policies and practices that pretend to address high crime levels, but actually do not serve as a deterrent. DM

Gwen Dereymaeker is researcher at the Civil Society Prison Reform Initiative.

Photo by Ashraf Hendricks/GroundUp.

Become an Insider

Become an Insider