The recent passing of Fidel Castro, Cuba’s charismatic former leader and revolutionary hero, encourages J. BROOKS SPECTOR to consider the ties between America and that island and the images and memories that have been so important in that relationship.

The first time I ever thought about Cuba was probably around 1958. At that time, stories of a small but tenacious, often-bearded band of rebels was being described in sympathetic terms by reporters in their articles about the rebels’ struggle against Fulgencio Batista’s corrupt, dissolute dictatorship. Increasingly, such stories were appearing on the front pages of major American newspapers and reports on these events were even gaining brief reports on the national newscasts of America’s three television networks.

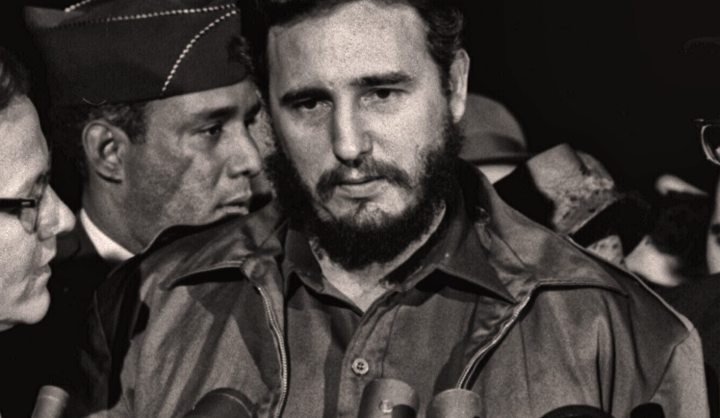

But it was the almost-as-it-was-happening-live-on-television newsreel footage (probably flown to Miami for broadcast nationally directly from Havana) of Fidel Castro’s guerrilla army’s triumphant entry into Santiago and Havana on January 2, 1959 (Cuban dictator Fulgencio Batista had suddenly abdicated and fled the country with $300-million, on New Year’s Eve) that made a major impression on me. Yes, it was grainy, black and white footage, but it showed the victorious young revolutionary leader, an obviously romantic figure – a kind of contemporary Byron in fatigues, or perhaps a young, bearded George Washington – poised atop an open-topped military truck, moving slowly through enormous, rapturous throngs on his victorious way into Havana. That was the same moment in time captured so vividly in the film, The Godfather: Part II, where the revolutionaries’ triumph is the backdrop for Michael Corleone’s hurried movement through those same crowds as he rushes to an abrupt departure from Havana.

Thereafter, the image of Fidel Castro, for many Americans, increasingly began morphing into something different from that of the dashing romantic revolutionary hero of those first days. There were the expropriations of land and businesses (including those belonging to Americans as well as those of other nationalities and, of course, of Cuban nationals). There were the arrests and interrogations. There were the increasingly bitter words exchanged between the new Castro government and the Eisenhower administration over such policies. And then there came the growing flow of Cuban exiles, departing their home island for the United States under duress or fear for the future. This was followed by Castro’s own harsh words at the UN about America, and increasingly strong threats by America to break off diplomatic relations with Cuba and its new government.

At the UN, there were the racy stories of Castro’s entourage leaving a downtown hotel after a snarl with the US government and hotel managers amid reports that the Cubans were partying very heartily and even grilling chicken on portable braais in their hotel rooms as well as restrictions on their free movement throughout New York City. Then came their transfer into a more picturesque but rundown hotel in Harlem in order to be closer to the downtrodden. Such moments were captured – without the grilled chicken – in yet another film, this time Alfred Hitchcock’s Topaz, as American and French espionage operatives attempted to figure out just what was behind the growing connection between Cuba and the Soviet Union.

And then there was the Bay of Pigs invasion. Late in the Eisenhower administration, once US-Cuban relations were auguring straight downward to a final crash, the CIA was given the presidential go-ahead to recruit, train, and arm a clandestine army of Cuban exiles. The plan was that their invasion would look as if it were a private effort, seemingly unrelated to the US government, and mounted by a group of patriotic Cuban émigrés eager, even desperate, to liberate their homeland from the clutches of Castro’s increasingly despotic, communist-heading regime. By the time the exile army, the “2506 Brigade”, was ready to go, a new president, John F Kennedy, had just taken office. He was reluctantly talked into supporting this invasion, and he acquiesced in part in order to demonstrate his bona fides to all and sundry – but especially within the national security parts of the government – as a vigorous leader of the free world, eager to push back against the incoming communist tide.

The invasion flotilla departed Nicaragua and headed to the south side of Cuba and on to a desolate, swampy landing zone – the Bay of Pigs – where virtually the entire force was killed or captured by Cuban forces after desperate fighting. Right before the collapse of the invasion force on the beaches, Kennedy refused to authorise direct US military engagement to attempt to save the landing party from defeat, sensing that such a move would mark the invasion as an American one, pure and simple. (American lawyer James Donovan eventually negotiated the return of all of the remaining members of the force a year-and-a-half later. This was the same man who had carried out the exchange of spy Rudolf Abel for U-2 pilot Gary Powers – and who was the central character in another film, the recent Bridge of Spies.)

But the resulting debacle that the Bay of Pigs became forced Kennedy to promise to the survivors publicly, once they had returned to the US, that their defeat would be avenged, and that eventually Cuba would be free from Castro’s rule. The inability of succeeding Democratic presidencies to redeem the Kennedy promise helped turn Cuban-Americans into a staunchly Republican-leaning group, and, as they gained US citizenship, into a potent source of Republican votes in elections. (In an ironic bit of history, some of the survivors of the 2506 Brigade would find themselves enmeshed in the Watergate break-in a decade later, supported by the Nixon Administration’s re-election committee.)

Meanwhile, Americans of the left had created the “Fair Play for Cuba” Committee as an attempt to counterbalance the increasingly popular view of Castro and his government as far-left enemies of America and allies of the Soviet Union. One person caught up in that group’s campaign was Lee Harvey Oswald, the man who would climb to the top floor of the Dallas Book Depository Building where, from his perch, he would assassinate President Kennedy on November 22, 1963.

One outcome of the Bay of Pigs invasion, of course, was the growing fear on the part of Castro’s government that it was only a matter of time before the US came up with a more successful plan for an invasion and the consequent regime change on the island. (Castro, himself, had a healthy fear of the possibility of assassination by one or another increasingly hare-brained CIA plot to assassinate him.) Meanwhile, Cuba’s growing ties with the Soviet Union allowed Castro (and Nikita Khrushchev) to attempt a two-fer out of the situation. Secretly placing nuclear-armed IRBMs in Cuba would provide a check on American ambitions to send Castro into an early retirement, and, at the same time, it would be a massive strategic gain for the Soviets in outflanking American nuclear strategic targeting on Soviet territory. Cutting delivery times of such weapons to reach American cities down to just a few minutes could become a major game changer – and a potential first strike weapon that could not be successfully countered by Americans with the weapons they had at that time.

Once the emplacement of these missiles was discovered via surveillance flights over the island, it provoked the worst geopolitical confrontation between the two Cold War adversaries in history. It became a two-week period when the possibilities of actual nuclear war were as close to realisation as has ever happened. Not too surprisingly, these events helped sear into American minds the image of Castro’s Cuba as a hotbed of Soviet efforts to destroy America, even as knowledge of Cuban efforts to export its revolutionary ideals to other nations in Latin America and the Caribbean basin (through the efforts and mystique of people like the Argentinian-born Che Guevara) led to diplomatic and economic isolation by the rest of the hemisphere’s nations and increasing American sanctions directed at Cuba. Such measures, of course, tied Cuba ever closer to the Soviet Union. Sales of the island’s main cash crop, sugar, and other aid became vital in assuring a continuing flow of Russian-made products and, most crucially, petroleum.

As reports came into the US from Cuba – and especially from the testimony of those who had escaped the island – it was increasingly clear that for many, Castro’s Cuba was an increasingly autocratic nation, complete with a tropical gulag for political and other dissidents. Such information only encouraged a further tightening of economic and political sanctions by the US Congress. And it was the bearded, cigar-smoking Fidel Castro who loomed over all of this as the chief evildoer resident in Havana.

Even in the midst of the Cold War, not everyone in America was convinced the isolation of Cuba was the right course of action. From 1969 onward, as part of the growing radicalisation of American university students, Students for a Democratic Society helped recruit student volunteers to go to Cuba – via a circuitous route through Czechoslovakia to avoid those US economic sanctions – in order to work on sugar cane harvests, the so-called Venceremos Brigades. (The first group included some 200 student volunteers from many college campuses, and the effort continued for many years.)

Some of these students actually came from my own university and were acquaintances of mine, although such travellers had little impact on the broader American society, let alone government policy. Nevertheless, they did keep some attention focused on the idea that this frozen-in-amber isolation of Cuba could not be a permanent answer to things. There were also frequent performances by popular folk singers across American college campuses and in other concerts of the Cuban revolutionary anthem, Guantanamera, with its mesmerising tune and lyrics by 19th century poet and independence fighter José Martí. Martí, it turns out, had been a spiritual inspiration to Castro as well in his formative years.

Castro, of course, had his own tie to American culture. While it is not true he had an actual pitching try-out with the champion New York Yankees baseball team, he did participate in a summer training camp run by the more lowly Washington Senators while he was a student, but his skills were not up to being invited to try out for the team itself – as bad as it was. Apparently he, like so many other young pitchers, had trouble with the curve ball, roughly equivalent to a googly for you cricket fans. Just imagine history if he had been able to throw a mystifying curve ball and had been snapped up as a genuine prospect, instead of giving him the free time to head off to the mountains on his quixotic quest for a national revolution instead.

By 1980, the Castro regime was in economic trouble and allowed a whole new group of dissidents, the so-called “Mariel Boat People”, to flee Cuba in a semi-organised wave of emigration by sea in various little craft and rafts. Not too surprisingly, the Cuban authorities were rumoured to have included criminals and mental patients in this flotilla as well, to help bedevil American authorities. This flight of people on some 1,700 craft helped reinforce the feelings of many Cuban-Americans in Florida that any change in the relationship could have dire domestic political repercussions for any American politician brave enough or foolhardy enough to support such changes. Such changes would simply help support Castro’s grip on the island.

The end of the Cold War and the collapse of the Soviet Union, however, began to force modest political but especially economic changes upon the Castro regime as Russia was no longer capable of underwriting the Cuban economy. But still boat people managed to depart Cuba illicitly, including a number of star baseball players and a small boy, Elian Gonzales, who quickly became caught up in an international custody battle, as well as the larger geopolitical struggle between American and Cuba. When he was finally repatriated to Cuba, the iconic photo showed the child being wrenched from the arms of his Florida relatives by heavily armed police and immigration officials – further cementing the idea that Castro and his government were antithetical to the very idea of human rights – even for a small boy who had only wanted to grow up in freedom with his uncles and cousins.

Of course, Cuba was also embroiled – or willingly engaged – in the struggle then taking place along the border between Angola and South West Africa/Namibia. Ultimately tens of thousands of Cuban soldiers participated in this fighting and, especially at the battle of Cuito Cuanavale in 1987-8, they were credited with being the key to the defeat of the South African Defence Force that was trying to hold onto that territory and to keep any insurgents from reaching any actual South African turf as well. The Cuban general who had masterminded the fighting, Arnaldo Ochoa, was eventually tried and killed in Cuba for various charges, including drug smuggling, but perhaps, too, for being too popular with the nation and thus a possible threat to the authoritarian Castro government.

For many Americans, especially during the Reagan and George HW Bush presidencies, Castro’s long involvement on the African continent was apparently aimed, ultimately, at a South African revolution and the support of other communist regimes across the continent. This was clear proof of the aggressive, revolutionary attitudes and actions of Castro’s Cuba on behalf of a still-dangerous Soviet Union, even as the final stages of the Cold War were actually playing out.

As the Cold War ended and as the role of an increasingly elderly Fidel Castro slowly faded from the scene, American attitudes finally began to shift slowly with respect to Cuba. Sports and cultural exchanges began to take place, including some widely touted baseball exhibition games played in Cuba and in Baltimore, Maryland. Orchestras and other musical groups started to take such trips between the nations, and a growing number of Cuban ballet dancers from the country’s highly esteemed national dance academy under Alicia Alonso began dancing in America as well.

Slowly, the Obama administration began to loosen elements of the economic and financial sanctions that had restricted commerce, although a handful of laws continue to limit what a president could do by executive orders until Cuba made major domestic political changes. Perhaps one of the most subtle ice-breakers came during the Ebola crisis last year in West Africa, when American officials let it be known that co-operation between American and Cuban medical teams on site would be possible, especially given the terrible impact of the epidemic and the need for the greatest possible co-operation between nations in combatting it.

And so, finally, after decades of diplomatic isolation of Cuba by the US, President Obama took the step of reaching agreement with Cuba – now Raul Castro’s Cuba, as his older brother Fidel was nearly invisible in retirement – to resume full diplomatic relations between the two nations. The two countries obviously still had lots to talk about, not least the repressive nature of Cuba’s political life and America’s remaining economic restrictions against the island. Anger about this Cuban repression potentially was a potent reserve of feelings against the resumption of relations by three or four generations of Cuban-Americans who had emotional ties to their lost lives in Cuba.

But for many such people, especially younger ones, relations with Cuba represented opportunities for business, for family reunions, and for the re-establishment of the kinds of ties to an ancestral homeland important to most hyphenated Americans.

And most important, politically, the vise-grip on politicians who were considering relations with Cuba exercised by the late Jorge Mas Canosa’s Cuban-American National Foundation had started to weaken as successor generations of Cuban-Americans have grown up and begun to take the political lead instead of the Bay of Pigs generation. By the time Obama moved to re-establish relations, surveys indicated a majority of Americans – and even Cuban-Americans – felt it was time to do so. But, in Little Miami, the other day, when people heard the news of Castro’s passing, it was still, for many, a chance, one more time, to show their anger – one last time, perhaps – at their lost world, as they came out onto the streets in their thousands to celebrate his death.

Still, the official view as expressed by President Obama now was, “At this time of Fidel Castro’s passing, we extend a hand of friendship to the Cuban people. We know that this moment fills Cubans – in Cuba and in the United States – with powerful emotions, recalling the countless ways in which Fidel Castro altered the course of individual lives, families, and of the Cuban nation. History will record and judge the enormous impact of this singular figure on the people and world around him.

“For nearly six decades, the relationship between the United States and Cuba was marked by discord and profound political disagreements.

“During my presidency, we have worked hard to put the past behind us, pursuing a future in which the relationship between our two countries is defined not by our differences but by the many things that we share as neighbours and friends – bonds of family, culture, commerce, and common humanity. This engagement includes the contributions of Cuban-Americans, who have done so much for our country and who care deeply about their loved ones in Cuba.

“Today, we offer condolences to Fidel Castro’s family, and our thoughts and prayers are with the Cuban people. In the days ahead, they will recall the past and also look to the future. As they do, the Cuban people must know that they have a friend and partner in the United States of America.”

And one might have thought this sea change in relations would have put an end to the sources of acrimony, save for the fact America had just been through a presidential election. Following Castro’s passing, President-elect Donald Trump had tweeted on November 28, “If Cuba is unwilling to make a better deal for the Cuban people, the Cuban/American people and the US as a whole, I will terminate deal.” And The Guardian reported, following Donald Trump’s tweet, “…conservative Cuban Americans – including Mauricio Claver-Carone, a hardline member of Trump’s transition team – have said the regime run by Raúl Castro, Fidel’s brother, is just as repressive, and argue that some or all of the sanctions should be reinstated.”

Cuba, and especially Castro, even in death, has managed to be a challenge for America and Americans for half a century. Castro managed to outlast 10 consecutive US presidents, and nearly had his 11th one on his personal score sheet as well. In fact, Cuba has been an obsession for Americans right back to the mid-19th century when many Americans thought the obvious next step for American expansion was to annex Cuba from Spain (or, perhaps, simply buy it from a dissolute Spanish monarchy hard-up for cash).

Eventually, in the Spanish-American War of 1898 (sparked by the mysterious explosion aboard a visiting US naval vessel while moored in a Cuban harbour), Americans defeated Spanish forces and liberated the island, allowed it to become independent in 1903, but kept clearly subservient to the American economy, the site for a naval base at Guantanamo under permanent lease, and as a playground for tourists and much worse.

Since 1959, it sometimes seemed as if Castro’s Cuba and America had played out the age-old competition between the mongoose and the cobra. But instead of an end to the problems, there is still another chapter left to write with Donald Trump in office, even as Fidel Castro is laid to rest with full honours and throngs of international mourners. They will praise the passion he inspired and his struggle, but they probably will leave out the untidy bits that had kept his government firmly in place under the tropical sun. DM

Photo: Fidel Castro in Washington, 1959. (Wikimedia Commons)

Become an Insider

Become an Insider