J. BROOKS SPECTOR visits his barber and that starts him thinking about the effect of the Trumpian political revolution on Africa.

There has always been an idea in America that wisdom flows from the mouth of one’s barber (or hairdresser), or from among the people who gather together at the barber shop to chew over the news of the day. In popular culture, the barber acts as a clarifying lens for ideas, drawing attention to small but important facts.

And so, the other day, while I was in the chair, with the barber clipping away at my hair and trimming my beard, he told me that following Donald Trump’s election as US president, he was going to buy as many shares of stock as he could in cement companies. Cement companies? Of course. Right. Walls (like that “big, beautiful wall between the United States and Mexico”) are built from bricks and cement (along with steel rebar and some other big, heavy stuff). Moreover, those promised massive new infrastructure efforts to rebuild highways, airports, harbours, and bridges are all going to be enormous consumers of cement too.

That, in turn, reminded me of my first arrival to Lagos, Nigeria, by air, way back in 1975. Describing a large 360-degree turn before heading towards the runway, the pilot of our airplane took the opportunity to show his passengers the astonishing sight of hundreds of cargo ships queued up in the sea, well beyond the entry to the port as far as the horizon. They were waiting to offload their cargos of cement that had been ordered by a slew of Nigerian government agencies for a massive construction boom.

All this cement was being paid for by Nigeria’s sudden gush of oil revenue riches after OPEC hiked the price of petroleum following the 1973 Yom Kippur War in the Middle East. This vast tonnage of cement purchases helped increase raw cement prices globally. But there was another consequence. So much had been ordered, in such a haphazard, higgledy-piggledy manner, with little attention to work schedules or the ability of the Nigerian economy and construction industry to absorb raw materials, that the vast queue of ships was anchored at sea for months, and the warm, humid, tropical sea air eventually solidified the cement in the holds of many of those ships such that the vessels were only useful to be sunk as underwater barriers and turned into artificial reefs for the benefit of the fish and coral.

My barber is itching to get in on the feeding frenzy for cement early in order to make his fortune so he can buy a yacht and the top-line Harley Davidson cycle of his dreams, once Donald Trump’s massive building projects begin to consume the world’s cement supplies – and prices, profits, and stock prices spiral upward in a 21st century version of a tulip bubble.

Maybe he should check out shares of Dangote’s cement company here in South Africa, or perhaps all the other global cement suppliers with local affiliates, before everyone else gets in on the act as well. Or perhaps Jared Kushner and Ivanka Trump, as some of the now-publicly named managers of the Trump empire that will be in a blind trust that will have at least one eye open, have already started to buy up cement supplies themselves, just in case…. We’ll return to the theme of infrastructure shortly, just in case you think this is an unnecessary diversion.

Anyway, Washington is now thoroughly awash with rumours and stories about a president-elect transition team that already seems to be going off its rails. In just a few days, the original leaders of this essential process have been replaced. This is crucial stuff since a new president must decide on his entire cabinet and dozens of other senior officials, as well as at least make a dent in naming some of the 4,000 or so appointed officials who will be installed after 20 January – and all within in the next two months.

The first people designated to run this transition process, New Jersey Governor Chris Christie as its chair, and former Congressman Mike Rodgers as its hands-on leader, were edged out almost before they began, and Vice President-elect Mike Pence was catapulted into this task instead. (For the enjoyment of real cynics, it turns out Jared Kushner was apparently responsible for this little bloodless coup d’état. Christie, as a federal prosecutor, had been responsible for putting Kushner’s father in the federal big house a few years back and so what goes around, comes around, it would seem.) This may also put paid to Christie’s hopes for a top-line cabinet appointment, if Kushner has anything to say about it.

In the meantime, to staff out the various committees within the transition team, and apparently at some variance with the Trumpian pledge that he would clean out what he had termed the “Washington swamp” and chase the money changers, er, lobbyists, out of the process, it turns out that a whole passel of lobbyists have been installed inside the transition team. As French policeman, Captain Renault, says in the classic flick, Casablanca, “I am shocked, shocked that gambling is going on in here.” [There! Finally worked that line into a story!]

Staffing a new president’s administration is not the kind of process where a bunch of display ads are put in a major newspaper. A whole team that must evaluate resumes, letters, e-mails and phone calls from hordes of eager, would-be officials. Some of these are experienced, thoughtful people; some are probably close to unhinged. Some are ideologues and thoroughly well-wired folks from within the winning political party, and they must be put into positions somewhere, but only where they can wreak as little havoc as possible on the work of government.

The task of putting this jigsaw puzzle together requires knowledge of a president’s views, but also an understanding of the actual workings of government, and the ability to separate the potentially good folks from the lunatics, all without antagonising the latter’s politically potent sponsors. And there is really very little time to accomplish this. The moment Barack Obama, private citizen, leaves the White House, his entire team will have departed as well, leaving the executive offices of the White House virtually empty, save for cleaners, technical support staff, guards and telephone switchboard operators to welcome an incoming wave of neophyte staffers.

Similar scenes will be enacted throughout the offices of cabinet departments, although in many cases, career civil servants will take on the titles of acting this or acting that, until political appointees can be identified, vetted, proposed to the Senate as required by law and the Constitution, and their confirmation hearings can be scheduled by the new Congress. Parenthetically, the gossip was that Donald Trump was flummoxed to learn these minor but telling details the other day, at his first meeting with President Obama, following his electoral victory.

If this seems arcane, just wait until Donald Trump starts trying to set out his legislative agenda and his policy goals and attempts to get even a Republican Congress – Senate and House of Representatives both – to sign on to everything he puts forward. Congress guards its power of the purse rather religiously (and it likes to dole out the goodies in terms of special tax breaks, policy tweaks and regulatory guidance that benefits those who may have some quiet clout on Capitol Hill). Will it actually authorise the massive spending increases for infrastructure builds, together with tax cuts, despite these things coming from the Trumpian White House, just like that, on order from Mr Trump? And every item he wishes to change or Obama decision he wishes to review and reverse will doubtless have constituencies and supporters within Congress, among lobbyists, on the part of industries and business sectors, and on and on and on, as well. There will be fights between the Trumpian populists and the GOP budget hawks, and between social conservatives and others, perhaps even on things like “abolishing Obamacare” that initially would seem to be like slam dunks for the new guy in the Oval Office. The insurance industry will have views on such proposed changes, now that they have thoroughly changed their operating models to accommodate Obamacare.

If these questions are still largely terra incognita, the actual impact of a Trump presidency in foreign affairs as it affects Africa and South Africa would seem to be almost impossible to discern so far, given that the names to be appointed to the top jobs in the State and Defence Departments, the US Trade Representative, the USAID director, the National Security Advisor, and so forth have yet to be publicly announced – or even, probably, decided upon. Still, we can pick up some major threads to take a few guesses about what may be in store for this continent at the dawn of the Trumpian Age.

One thing that would seem inevitable would be a hunt for financial resources within government budgets that can be shifted around to support the new president’s agenda. This is easier said than done, as every existing programme has its supporters, but if his infrastructure build is a serious thing, the new administration is going to be on the hunt for every penny it can find. Consider foreign assistance-style programmes, for example.

For years, Trump has expressed negative feelings about them, arguing that they are a waste of time and money. Specifically, the narrative may be that as far as Africa is concerned, since it is a place that generates the kinds of nasty, intractable problems America should stay clear of whenever possible – maybe the government should just save the cash for something else more important. In his commercial career, there have not been any Trump office towers or hotels in Africa, have there? Well, of course, a snap of the fingers won’t end such aid but it will provoke nasty bureaucratic fights, the moment the idea comes up.

Similarly, he and his team may have relatively little enthusiasm for things like the Millennium Challenge Corporation and Pepfar, the anti-HIV/AIDS programme (both originating from George Bush’s presidency), and the newer Power Africa and the Young African Leadership Initiative – Yali – (President Obama’s two signature initiatives towards Africa). Moreover, if the president-elect’s earlier statements and the leaks coming out of his transition team have much merit, early on in his presidency he will begin to push aggressively on new bilateral trade negotiations and to begin dialling back US support for commitments under the Paris Global Climate Change Accord.

In the post-Cold War-world, Presidents Clinton, Bush and Obama have all focused on expanding American trade with Africa, rather than simply adding more direct foreign aid. The underlying concept was that a growing trade relationship generated a more stable economic climate. That, in turn, resulted in a more stable political situation – and that led to growth in support for democratic values and practice once people had stakes in the future.

As part of this strategy, the US Congress has continued to extend the African Growth and Opportunity Act (AGOA) – this most recent time for a further 10 years. Further, Congress passed the Millennium Challenge Corporation into law in 2004. (This agency co-ordinates its investment portfolio with host countries for jointly developed infrastructure development projects.) During the Obama presidency, the Power Africa and Food Security Acts joined the game too and all of these have had significant bipartisan support over the years.

Admittedly there is no evidence yet that the new president would try to pull the rug out from under any of these specific programmes, or even that he has thought about them much. Still, what he has made clear is that he has a tough-minded trade agenda. He wants to renegotiate the trade agreements the US is party to such as the North American Free Trade Area, or NAFTA, in order to secure “better” terms for America. AGOA, in its present status, would outlast even a second Trump term, but it is not inconceivable, if Trump-style protectionism gained momentum, that some of the features of that law might come under review or amendment in future.

Witney Schneidman, a non-resident fellow of the Brookings Institution think tank and long-time analyst of US-Africa trade relations, in thinking about the salience of Africa for a Trump presidency, concludes, “…there is no evidence that Africa will be a priority for President Trump in the way it has been for his three immediate predecessors. In fact, there is every reason to expect that, under a Trump administration, the US will be less engaged in Africa especially where it concerns the expenditure of taxpayer resources on economic development initiatives.”

In response to such concerns, the US Embassy in Pretoria responded to our questions about the incoming Trump administration, saying they were optimistic that “his administration will view South Africa as the long-term strategic partner and friend to the United States that is has been for many years. Across Republican and Democratic administrations, we have viewed South Africa as a key international player and partner we have worked with in response to health and environmental crises, to promote trade, security, improve infrastructure, promote human rights, and integrate markets across the continent.

“The US and South Africa have a robust economic relationship. The United States is South Africa’s third-largest trading partner and South Africa is a key export destination for the United States. Two-way trade in goods topped $13-billion in 2015. And approximately 600 US companies are active in South Africa, accounting for 10% of South Africa’s GDP. So, we have a long-term strategic interest in South Africa’s prosperity and remain optimistic that our relationship with South Africa will remain on the same path it has been since 1994, during which our partnership for prosperity has grown and matured.”

Noting AGOA’s place in this landscape, they added that the US Government hopes that “South Africans will continue to take advantage of this benefit, which provides South African companies duty-free access to the largest single market for most products in the world. More than 98% of South African exports enter the US duty-free under various trade preference programmes, including AGOA.”

Similarly, the embassy argued that other programmes like Pepfar and Yali have enjoyed bipartisan legislative backing and they expect this to continue, even under the Trump administration with its laser-like focus on fixing unfair trade agreements.

Speaking of that Young African Leaders Initiative, Schneidman argues instead, “It is difficult to see this effort being sustained by a President Trump, although it would be in US interests to do so. In fact, most Africans are wondering if the Trump administration will impose a ban on Muslims [as Trump’s campaign rhetoric argued for], will expel the large numbers of African immigrants, and whether the US will continue to be the beacon of hope, friendship, and opportunity that it has traditionally been to many on the continent.”

Beyond the economic relationships, with the Trumpian rhetoric about making the US’s allies and partners take more responsibility to attend to their own security needs and costs, a question should be asked as to whether or not the new administration will be as engaged with African security challenges as the Obama administration has been. These could include its current support to nations coping with Boko Haram, or the peacekeeping efforts in the Congo, Somalia, and South Sudan. Again, we are still looking for a whisper of a sign on the future directions of the Trump era. Accordingly, real indications from African nations about the importance and impact of such partnerships might have a positive impact in generating a climate for maintaining such American support.

Looking to Africa itself, supporters of the recent Paris climate accord may have some reasons to be concerned as well, given Donald Trump’s previous statements that he believes climate change is really a hoax perpetuated by the Chinese to allow them to keep the value of their currency artificially low and thus their exports high. Climate change is, of course, a major concern for many African states, including South Africa, given the impact climate change can have on fragile food security, water resources, the growth of desertification, and possibilities of rising sea levels.

In this regard, University of Maryland public policy scholar Nathan Hultman argued the other day, “Donald Trump’s election raises the question of whether the US will continue to be a leader on climate change and clean energy. After a long and arduous process with strong US leadership to organise international action on climate change, momentum had been built behind the current process of nationally determined goals and nationally designed strategies. Within the US, there will be questions about whether climate strategy will be undone.”

Finally, we circle back to infrastructure – and my barber’s plan to corner the global market in cement and make his fortune. A key feature of Donald Trump’s presidential campaign was a promise of a massive infrastructure programme. If US government spending rises for this programme, it might well generate higher interest rates (and thus inflationary pressures), if the US increased government borrowing to deal with these costs. On the other hand, if it tried expansionary monetary policies, in tandem with increased deficit spending, that could lead to higher global inflation. Moreover, a vast American infrastructure boom, leading to a rise in the cost of capital globally, would lead to higher costs of borrowing for infrastructure development by Africa’s own governments. There’s that old adage again, the one that says, “When America sneezes, the rest of the world catches a cold.”

The next two months of the transition and then the first months of the new administration will undoubtedly be confusing and frustrating for many, as Donald Trump moves on from the easy certitudes of his unlikely electoral win and begins to come to grips with the realities of political and governmental power. And maybe my barber is on to something big as well. DM

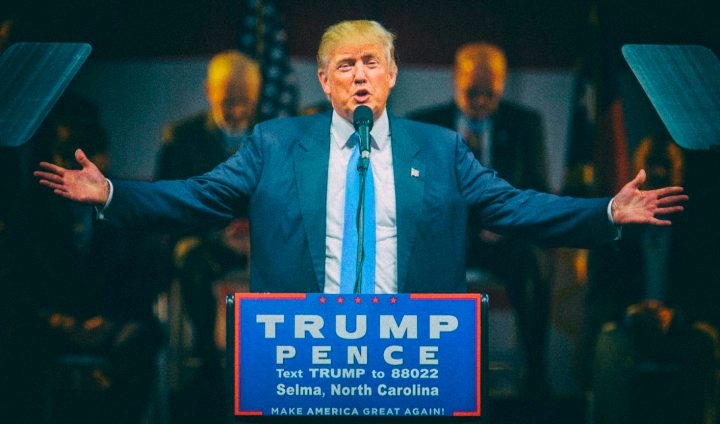

Photo: Then US Republican Presidential nominee Donald Trump holds a campaign rally at The Farm in Selma, North Carolina, USA, 03 November 2016. EPA/JIM LO SCALZO

Become an Insider

Become an Insider