South Africa

Op-Ed: The crisis in our universities is a symptom of a wider social crisis

The social tensions that have manifested in our universities are not just a result of problems in the universities. They are also expressions of the wider problems that pervade our society and have deep roots in the racial capitalism that has shaped our country. By VASHNA JAGARNATH.

One part of this toxic legacy is that the bulk of the education system was not designed and developed to cultivate independent thought for democratic citizenship. Over the years, both students and academics developed important ruptures within the logic of domination. However, the system as a whole was designed as a tool to discipline the working classes, peasants, not just in the colonised spaces but also within the metropole. Where it was designed for elites it was often developed to train a colonial elite to manage a rapaciously racist system.

Effective reform of the education system inherited from colonialism and apartheid requires political will and significant social investment. However, after apartheid that political will was often lacking in our universities, and the ANC, following the model of a structural adjustment programme, seriously underfunded universities. In Cuba, 4.47% of the GDP is invested in higher education. In South Africa the figure is just 0.71%.

But while the ANC must be held to account for its failure to invest in universities, we must acknowledge that the crisis of universities is also international.

As capital has increasingly escaped control of the nation-state, the social democratic mechanisms for redistribution and social investment via taxation have been weakened. One result of the increasing power of capital over nation states is that public education, with its democratic possibilities, has declined and private education, often orientated around servicing the market, has expanded.

The debate and struggles around access to university education are far from unique to South Africa. There have been similar struggles across Africa – often resulting in long shutdowns, sometimes for years at a time. In light of the experiences elsewhere on the continent, Gwede Mantashe’s recent utterances are highly disturbing. In recent years student protest around the question of fees and access have also arrived in countries like England and the United States, as well as India and Chile. In all of these countries there has been serious police repression of student struggles.

We are all aware that there is a deepening social crisis in South Africa. Generally its morbid symptoms, like xenophobic pogroms, the emergence of charismatic demagogues or looting from the parastatals, garner more media attention than the crisis itself. However, it is important that we examine the disease as well as its symptoms.

Mass unemployment has become a systemic feature of our society as capital abandons manufacturing and mining in favour of finance and debt-driven consumption, or exits the country altogether. In our cities, apartheid spatial planning has not been overcome and millions remain in shanty towns. In rural areas the corporatisation of agriculture and the neo-apartheid return to traditional authority has produced mass impoverishment and domination. Public schooling is in an atrocious state.

This social crisis has always been present in historically black universities, which are also universities for the working class and the poor. In these universities there have been struggles over the question of access since the end of apartheid. But now that these struggles have entered the elite and formerly white universities, they have become a major national issue. The way that this crisis was largely ignored when it was contained to black working-class institutions is itself a collective indictment on our society.

It is understandable that some students have prioritised the university as a terrain of struggle, as it is accessible to them. However, when students have placed the primary pressure for access on university managers rather than the state, they have made a serious error. The ruling party, and the capitalist class of all races whose interests it protects, needs to be called to account. There is a real risk that the demonisation of individual vice-chancellors could result in their replacement by the kind of ANC functionaries that have done so much damage to the parastatals and the SABC.

But to the great credit of the student struggle there is now a general consensus that a new funding model needs to be developed. The debate is between those who take the view that fees should not be part of the new model and those that argue that the rich should continue to contribute to the system in the form of fees. Proponents of the first position take the view that increased tax on the super-rich, as well as mechanisms to stop illicit capital flows out of the country, can enable free education. Others have noted that stopping corruption and wastage – and unwise spending like the trillion-rand nuclear deal – could free up money for social investment.

Proponents of the second position argue that middle-class and rich students have greater access to university as they have better access to quality school education in a situation in which public schooling is largely dysfunctional. They argue that this means that free education across the board would, in fact, be a subsidy for the rich. Some who take this view have also argued that the super-rich, and corporates, are good at evading tax and that the damage that Zuma has done to the credibility of the state, and to the integrity of its institutions, place limits on the ability of the state effectively to raise more revenue and to invest it in social projects.

However, any attempt to resolve the crisis that is now manifesting itself in the elite universities without resolving the wider socio-economic and political crisis – the crisis of continuing capitalist and imperialist exploitation of South Africa (both phenomena that are intensely racialised) – is destined to run into serious limits. Universities cannot flourish amid an unfolding social catastrophe, nor can they somehow compensate for that catastrophe.

We need a new economic order and a new rural and urban order. We need to radically restructure the economy, the cities and the countryside – to overcome poverty, unemployment and inequalities. We need to ensure that there is decent work or a decent income, as well as decent education – from school onwards – for all.

If we are going to have any chance of achieving a socialist resolution of the crisis the often valiant struggles against different dimensions of our crisis need to be brought together. University struggles need to build solidarity with the struggles of the working class and the poor to build a mass movement for fundamental social and political change. We must also acknowledge that the international power of capital and imperialism means that this is not a project that can be successfully undertaken in isolation.

In order for this project to have any possibility of succeeding we need to be clear-sighted about the social forces that have emerged out of the crisis. There are progressive and democratic forces on and off campuses. But there are also forces that have taken the form of authoritarian populism, that have expressed themselves in demagogic ways and that have been complicit with xenophobia, homophobia, sexism and anti-Semitism.

On some campuses, large democratic movements in which women were at the forefront have been replaced by smaller, more authoritarian and masculinist forms of politics. The kind of political opportunism that finds it expedient to overlook the dangerous political content of reactionary populism will very soon run into serious trouble. DM

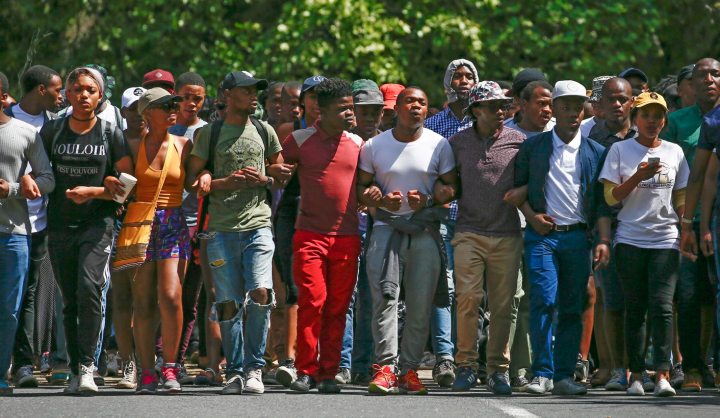

Photo: Students and supporters protest in support of the #FeesMustFall campaign at the University of Cape Town (UCT), South Africa, 04 October 2016. EPA/NIC BOTHMA

Become an Insider

Become an Insider