Africa

Zambia at a Crossroads: A Break from the Politics of Identity?

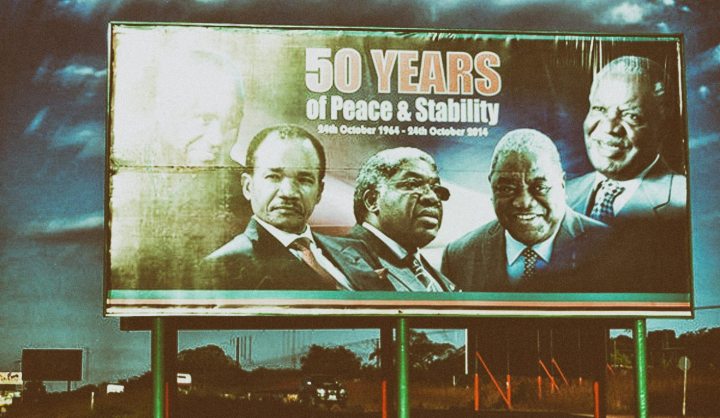

Given that so much is going wrong and that so many ordinary Zambians are feeling the economic heat, the country should be ripe for political change as Zambians go to the polls on Thursday. More than 50 years after independence the country is now officially the most unequal country in the world. By GREG MILLS and DICKIE DAVIS.

Our favourite Zambian taxi-driver poll, pursued against all the advices of hardened journos, asked: “Who will win the election?” When the answer came back “Edagah”, in selecting the incumbent president Edgar Lungu, the answer to the follow-up was, invariably, “Because HH is too tribal”. Such drivers were usually from Eastern Province, Lungu’s support base. When it was pointed out that “this meant that they were too tribal”, the response was a smile, splutter and the occasional curse. Ironically, much of the rest of the conversations dwelt on the increasing cost of living, job losses, fuel shortages and power cuts.

In the upcoming election this Thursday, August 11 2016, Lungu’s challenger is businessman Hakainde Hichilema – better known as HH.

This is probably HH’s best chance of winning the presidency after four previous attempts; the first in 2006, then in the by-election following President Levy Mwanawasa’s death in office in 2008, again in 2011, and most recently in 2015. On the last attempt, the by-election following President Michael Sata’s demise, Hichilema lost by just 27,757 votes (or 1.66%, and inside the margin of error) against the ruling Patriotic Front’s candidate Lungu.

The run-up to this election has been messy, with allegations of electoral fraud over both the voter’s roll and the printing of ballots, and marred, perhaps surprisingly for a country famed for its peacefulness, by election-related violence. In July, political campaigning in the capital, Lusaka, was suspended by the electoral commission for 10 days because of violent clashes. But the clashes have continued. In part these tensions are because there is so much at stake, and in part because the Zambian economy is in dire straits.

The economy, which is still dependent on copper, has tanked. While it may have weathered the downturn in Chinese demand for the commodity, four changes in mining tax laws since 2011 have undermined investor confidence, despite continuous returns to government since the mines were privatised 15 years ago. The sector has consistently provided 80% of export income, 12% of GDP and around one-third of all tax income since the mid-2000s.

Even the government has noted its own goals. As the Minister of Finance told parliament in April 2016, such policy changeability damages Zambia’s investor credibility which “is anchored on two themes: predictability and consistency. If somersaults are going to be our recipe, such will reduce investor confidence in our country.”

Other indicators too are poor. During 2015 the Kwacha fell by more than one-quarter of its value, making it the worst performing currency worldwide.

This slide would matter less if Zambia produced stuff to export with which it could take advantage of the weakening exchange rate. Yet the number employed in commercial horticulture is, at 5,500, one-third of the number 15 years ago. Although the area of maize under cultivation has more than doubled in the last decade to 1.4-million hectares in 2014, yields and return on maize remain low, around two tonnes per/ha for smallholders. Commercial farmers have not planted maize for the last five years due to price uncertainties introduced by government’s role in the market.

Similarly, tourism has almost boundless potential. Yet the country receives at most just 150,000 fly-in international tourists a year. Neighbouring Botswana receives five times more wildlife tourists. Occupancy at Victoria Falls (Livingstone) is just 35% for hotels, and 15% for lodges, compared to more than 70% on the Zimbabwe side, despite all of that country’s special challenges.

Zambia’s economic woes have been compounded by increased debt and breathtakingly poor mismanagement.

Debt, from which Zambia was all but totally relieved in 2006, now stands at just under $10bn, or 50% of GDP. Much of the new debt taken out under the PF government, more than $3-billion in four years, has apparently been spent to fund civil service salary increases. The public service numbers 237,000 of the 625,000 people who are formally employed, and consumes half the budget. Public service salaries have increased by nearly 60% in real terms since the PF government took over in 2011.

The system works well for about 1.5-million of the 16-million Zambians. More than 50 years after independence the country is now officially the most unequal country in the world. Today the top 10% of Zambians receive 52% of income, while the bottom 60% of the population just 12%.

Total debt servicing costs are estimated at 17% of the budget (or 3% of GDP) in 2016, or $850-million. There is a larger crisis just around the corner. $750-million of debt matures in 2022, $1-billion in 2024, and $1.25-billion between 2025 and 2027.

To add insult to injury, load shedding is increasingly frequent as the water level in Kariba has declined due to overuse of peak generating capacity, along with delays in commissioning new power projects.

In his defence, Lungu’s supporters say he has not done badly in his just 18 months in office. They argue that he has delivered on Sata’s infrastructure programme, which has built new roads, but that he has been a victim of the worldwide commodity price crash, and that he needs a full term with a team of his choice to demonstrate his true worth.

.jpg)

His critics, on the other hand, say that as the minister of justice, defence and now president, Lungu has been an integral part of a government with an extremely poor development record.

Given that so much is going wrong and that so many ordinary Zambians are feeling the economic heat, the country should be ripe for political change.

HH is acknowledged as an effective businessman, a rags-to-riches story, one who seems to have the skills to match the country’s economic challenge. But he is from the south of the country. Indeed, there has never been a southerner, a Tonga, as president of Zambia, despite the promise of Harry Nkumbula, the leader of the African National Congress, outmanoevered by his erstwhile colleague Kenneth Kaunda in the creation of a one-party state in 1973; and, subsequently, Anderson Mazoka, HH’s predecessor as head of the United Party for National Development (UPND).

Still, the issues should trump comparatively banal politics of identity. Whoever wins, the IMF is going to have to step in to assist, given the scale of the problems of debt and liquidity. The utility of this assistance will be determined by whether there is sufficient desire to reform domestically or to do so only under pressure from outside. Yet the reason why Zambia is characterised by widening income inequality is precisely because the elite has operated largely in its own interests.

In the absence of non-state alternatives, in the zero-sum game that is Zambia’s political economy, the run-up to the election has seen increasing violence, interference with the limited free press, and restrictions on campaigning. HH has said that the elections cannot be regarded as free and fair. Lungu has said that if it came to a choice of peace or democracy, he would choose peace.

If the winner does not achieve 50% plus one vote, as required by the constitution, the election will go to a second round scheduled within 37 days. The violence and meddling can, in the circumstances, be expected only to increase.

The UPND is bullish. This confidence is not only based on the government’s economic record. Of the 6.7-million registered voters, more than one-quarter are calculated to reside in opposition strongholds in the southern, western and north-western areas, while the UPND has additionally made inroads in the high-density areas of Lusaka and the copper belt.

In this way, the outcome of the vote will probably reflect not only the health of the economy, but the state of Zambian democracy and national identity. DM

Mills and Davis spent several months in Zambia this year for the Brenthurst Foundation researching economic reform options.

Photos by Greg Mills.

Become an Insider

Become an Insider