Africa, Maverick Life

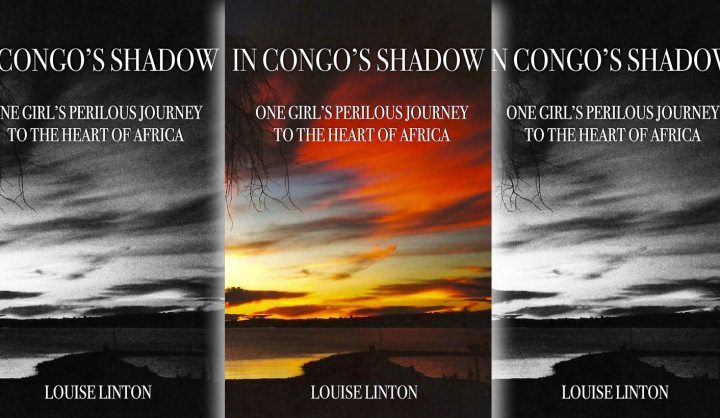

Shadow play: Louise Linton and the arrival of the African age

If the much-vaunted human apocalypse is anything, it is the failure of those claiming to dream our collective dreams to recognise our collective shadows. Enter Louise Linton and her memoir In Congo’s Shadow, which the Daily Telegraph didn’t spot for a fairytale. The ensuing Twitter storm, KEVIN BLOOM suggests, is a harbinger of our African future.

Why? Just, why?

This double-barrelled shotgun of a question, with the emphasis on both barrels so as to evoke the appropriate existential dread, appears to have become a species-wide meme of late. Take, for instance, Louise Linton’s silky blonde hair and flowing white blouse, framing her Estee Lauder lips and Audrey Hepburn eyes, which beseech us pensively from the photograph’s focal point to consider the headline above: ‘How my dream gap year in Africa turned into a nightmare’.

Why, Ms. Linton? Let us squander no more than a handful of words on the wounded angel herself: forgive her, for she knows not what she does.

The Daily Telegraph, on the other hand, the UK’s leading conservative broadsheet, retains that cast of British doggedness that can stand and take bullets all day. Why did Chris Evans, the newspaper’s editor, choose to publish this excerpt from Ms. Linton’s book? Why, when even the book’s title, In Congo’s Shadow, should have alerted him to the risk of viral social media scorn, did he allow the spread to go through? Why, in the face of the writer’s confession that she had come to Africa “with hopes of helping some of the world’s poorest people”, did he run the pages anyway?

The national lobotomy that has been visited upon the British public in the last fortnight presents itself as one of the possible answers. After four centuries of colonial plunder, centuries which have seen the soldiers and sailors of the Crown conquer (and reluctantly relinquish) the majority of the planet’s landmass, centuries which have set up the English language as humanity’s lingua franca and established paleness as the skin tone of choice, centuries which have funneled the earth’s natural bounty into British-built tax havens for the rich, the tumor in the host’s brain had by 23 June 2016 reached the point where only surgery could “save” the body. The Brexit operation, aside from costing the British their respect abroad and their economy at home, has by most early indications also cost them their discretion. Racism in the buses, xenophobia on the streets, an excerpt from Louise Linton’s book in the pages of the “Torygraph”.

“Needing my own escape and hoping to continue my mother’s mission to do good works in faraway places,” she writes, “I’d accepted a position as a volunteer at a commercial fishing lodge in Zambia. It was the most remote country on the list I was given and the one most in need.”

Of what?— as Chris Evans might have asked. But he didn’t, he let the story run on into the next paragraph, where Ms. Linton’s father entreats her to find a “bolt-hole” as soon as she arrives, somewhere ”to hide, just in case”. This time, Evans might well have asked “from what?” Congolese rebels, it turns out, which was one of the things that prompted the hashtag #LintonLies, a trend that quickly became a phenomenon covered by the likes of the BBC and the Guardian. Thing is, as of this writing, neither of these dominant British news brands have thought to name the name of the most senior person responsible—ref: Chris Evans—which loops us back to that national lobotomy.

And so, if we’re going to continue on this line, we have to go wider and deeper—into the realms of the unseen powers driving human psychological evolution. “The individual man knows that as an individual being he is more or less meaningless and feels himself the victim of uncontrollable forces,” wrote Carl Jung in 1958 in The Undiscovered Self, “but, on the other hand, he harbours within himself a dangerous shadow and opponent who is involved as an invisible helper in the dark machinations of the political monster.”

Evans, in this conception, is a stooge. But not just a stooge in the ordinary sense of the term—a stooge in the hands of the Daily Telegraph’s owners, say, who in a quest for survival have been steadily driving the 160-year-old broadsheet into tabloid-ism—no, Evans is a stooge in the hands of the collective unconscious. For Jung, the “common human shadow” was to be found less in the “barbarities and bloodbaths perpetrated by the Christian nations among themselves throughout European history” than in “the crimes [the European] had committed against the dark-skinned peoples during the process of colonisation.”

Still, to all darkness there is light, right? Here, then, is what Evans is mistaking for an oncoming train. On 29 June, two days before Ms. Linton’s ill-starred excerpt appeared in the Daily Telegraph, the website Africa is a Country republished an essay by the Cameroonian philosopher and post-colonial theorist Achille Mbembe. Entitled “Africa In The New Century”, the essay advances one of the most profound arguments yet for the growing—if still marginalised—hypothesis that the future of humanity is being subsumed by the future of Africa. The essay, which runs to over 5,000 words (and is worth every syllable of the read), finds its nut in the paragraph where Mbembe offers three comments about what he calls the “planetary turn”.

Each one of the three can be anchored in Evans’s zombie oversight.

“Firstly,” writes Mbembe, “that Africa is gradually perceived as the place where our planetary future is at stake—or is being played out—is due to the fact that, all around the world and especially in Africa itself, older senses of time and space based on linear notions of development and progress are being replaced by newer senses of time and of futures founded on open narrative models.”

What better evidence could there be of this statement’s truth than #LintonLies? If Evans and his readers believed that the Internet and social media had not arrived yet in Africa, they know it now. The hashtag’s continent-wide African popularity has resulted in new articles appearing in the global media by the minute—CNN, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times—and as I write on 6 July, although it still hasn’t mentioned Evans, the Guardian has posted an eviscerating piece by Zambian writer Lydia Ngoma: ‘Louise Linton’s Zambia is not the Zambia I know’. The narrative is indeed wide open; the old things falls apart, the new things come instantly (quantam-ly) together.

“Secondly,” writes Mbembe, “within the continent itself, Africa’s future is more and more thought of as full of un-actualised possibilities, of would-be-worlds, of potentiality. Many increasingly believe that through self-organisation and small ruptures, we can actually create myriad ‘tipping points’ that may lead to deep alterations of the direction the continent is taking.”

Here Mbembe is referencing the notorious African binaries: the enormous rises in sub-Saharan GDP growth versus the hundreds of millions still living below the poverty line; the dozens of democratic elections that have brought peaceful transfers of power versus the ongoing civil conflicts; the Internet and mobile penetration rates versus the lack of access to electricity. An example of something that could serve as a tipping point? Exhibit X:

“Even in this world where I’m supposed to belong,” laments Linton, “I still sometimes feel out of place. Whenever that happens, though, I try to remember a smiling gap-toothed child with HIV whose greatest joy was to sit on my lap and drink from a bottle of Coca-Cola.”

On a scale of 1 to 10, with 1 being “no tip” and 10 “full tip”, how pissed off are you?

“Thirdly,” Mbembe continues, “it has of late been a matter of tacit consensus, especially among international financial institutions and experts, that Africa represents the last frontier of capitalism. While this last claim is contested in various quarters, there is nevertheless ample evidence to support it.”

Mbembe provides two pieces of evidence to back up the claim, the second being that Africa is, “against all odds, a region of our world where some of the most far-reaching formal and informal experiments in neo-liberal deregulation have been taking place.” Although Ms. Linton’s hang-ups about endemic African poverty are ridiculous enough beside such facts, there are plenty more subtle examples of mainstream blindness—like the still-trending article published a year ago in the Guardian, “The end of capitalism has begun”, an item of Internet-focused utopianism that cites the US, the UK, the Eurozone, Greece, China, India, Iran and North Korea without citing an African country once.

“The power of imagination will become critical,” notes Paul Mason, in this otherwise appealing punt for his version of post-capitalism. “In an information society, no thought, debate or dream is wasted—whether conceived in a tent camp, prison cell or the table football space of a startup company.”

Precisely. But what some people seem to forget is that the real dreamscape, by definition the terrain of the unconscious, is where the internal shadows lurk. If Africa’s collective dream remains their collective nightmare, a place that waking consciousness refuses to acknowledge, the future will only get more hostile. Our saving grace? Africa, as demonstrated by #LintonLies, won’t let them forget. DM

Kevin Bloom is co-author with Richard Poplak of Continental Shift: A Journey into Africa’s Changing Fortunes, out now in select bookstores across Africa, Europe (still including the UK), Asia and Australasia.

Become an Insider

Become an Insider