Maverick Life, South Africa

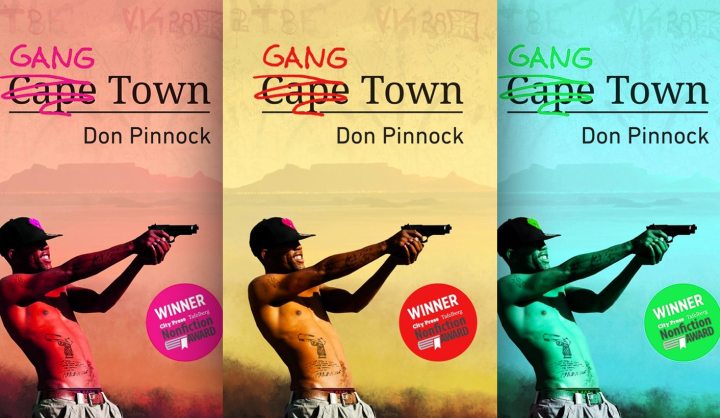

Book Review: Don Pinnock’s Gang Town wakes you up to a cold reality

You might not be entirely surprised by the contents of Don Pinnock’s Gang Town, especially if you know something about the Western Cape’s gangs. But if it’s a sensationalist account you’re after, this isn’t the book for you anyway. Gang Town offers a lucid, balanced account of the Cape’s gang structures, and what can potentially be done about it. It makes sense. By MARELISE VAN DER MERWE.

It wasn’t a pleasant task reviewing Don Pinnock’s Gang Town. Usually, reviewing books is one of the perks of being a journalist. This time, being the reviewer was a disadvantage.

Not because the book isn’t good. But because it’s not a book you want to read to deadline. It’s a book you want to read slowly, taking in every detail. You want to savour it.

Cape Town, South Africa’s gang capital, is Pinnock’s adopted city, and he’s spent the last 30-odd years as an investigative journalist and criminologist getting to know some of the area’s most notorious gangsters – inside and outside of prison. The book won the City Press/Tafelberg Non-Fiction Award and has been described as “[probably] the most important resource for generations of social scientists” (Jonathan Jansen) and “a startling insight” (Andrew Brown).

Gang Town is troubling, but it’s also a joy to read. Pinnock has taken such trouble with it, drawing on more than three decades of research, that there isn’t a sentence that doesn’t deliver. The text is so rich that you’ll find yourself pausing and re-reading sections several times over. It’s not an arduous read – for such heavy subject matter, the touch is surprisingly light – but Pinnock has managed to supply an exceptional richness of detail, slipping in the etymology of a term here, a first-person account there, some beautiful period photography and an assortment of respected sources from a staggering range of fields.

The book, in Pinnock’s own words, is “not about prison gangs in prison, but about their effect on those who are not”. It is, however, also much broader than that, probing the gangs’ history as well as making recommendations for breaking the cycle of gang membership. Pinnock doesn’t supply any particularly controversial arguments or state anything necessarily groundbreaking. Instead, he painstakingly and meticulously says what needs to be said. Inasmuch as critics may accuse him of stating the obvious, it’s also true that much of what’s obvious can pass under one’s nose every day without getting the attention it deserves.

Pinnock has written a deeply important book, assimilating the available data into a clear and readable format that is credible enough to pass academic muster but accessible enough to inform the layperson.

The book is divided into six sections which can be read as a whole or on their own:

- Gang Town: a history of the city’s geography and spatial planning, and the impact that apartheid laws had on relocated and fragmented communities;

- Cape Town’s Gangs: a tour of the city’s gangs, how they are formed and how they function;

- Understanding adolescence: a discussion of deviant behaviour during youth – what informs it, how it can be understood, and how young people can be better supported;

- Families in crisis: the familial roots of persistent deviance, and how social cohesion – or a lack thereof – is taking shape in South Africa, as well as neurobiological factors that may play a role;

- Toxic neighbourhoods: a discussion of the role of poverty, joblessness, a failing education system and high levels of drug availability; and

- Towards resilience, where Pinnock discusses some of the possible solutions to this long-term problem, including recommendations that can fit into existing frameworks in practice in South Africa.

Perhaps this book’s strongest selling point is that it is not shrill. It is a balanced, methodical examination of South Africa’s long-term battle with violent crime, with a particular focus on the gangs of the Cape. It approaches the plight of young people drawn to gangs with sympathy, but it is not blind sympathy. Instead, it calls for level-headed engagement with a problem that is not going away unless there is a concerted effort to build a multifaceted solution.

The statistics, as Pinnock puts it, speak for themselves:

In one year, between April 2014 and March 2015, there were six murders and seven attempted murders a day, 30,637 reported assaults (84 a day)… In the absence of recreational amenities, sound schooling or… stable family structures, young people have nothing to do but hang out in the streets, form friendship groups and fight or fuck each other. They do this in the knowledge that… death before the age of 30 is a strong possibility.

He adds:

To understand… we have to remember something important about our own adolescence: teenagers, above all else, are mythmakers… They need to perform to win respect.

Pinnock raises the issue that many of the young people who find themselves in gangs – and even those who do not – are in the first place treated as second-class citizens. He quotes that they are treated as “unwanted trespassers rather than citizens entitled to all the rights that the new Constitution guarantees”.

“The commitment of the post-apartheid state to a better future for all began to shift by about 2000 towards a better future for the few, and increasing management of the rest,” he argues.

A great strength in the book is its comprehensiveness. Pinnock has touched on many of the key fields of study relevant to adolescent development and youth violence today, highlighting some of the most important aspects of current thinking. Few stones have been left unturned. A crucial focus is that of Early Childhood Development, which Pinnock raises in Section 6, calling it “the obvious and critical place to begin”.

“If [the Early Childhood Development Policy Draft Document] is passed into law and effectively acted upon, it will be the most important step the country has ever taken to protect and support parents and young children,” he writes. “It would ensure and secure resilience in children and youngsters and lead to a reduction in gang activity.”

Pinnock further suggests interventions in community resilience, which include a widespread focus on safety, and a rethinking of education, pointing out that children who start school in 2016 will retire in 2075 – and that we do not currently know what the world will look like then or what skills will be needed, so more flexibility is probably required in education. Better after-school care facilities, he adds, is also a must, which was flagged in 2014 by Cape Town as an essential area for investment. Most important, in this writer’s opinion, Pinnock raises the failure of the justice system:

The cost of what the Minister [Sibusiso Ndebele] is essentially calling a failed institution is staggering. According to Nicro, in 2014 South Africa had 162,162 people in custody, 49,695 of them awaiting trial. This cost taxpayers, according to the minister, R399.20 a day to house each inmate and prevent them from escaping…

Between 1995 and 2014 the number of prisoners serving life sentences jumped by an astonishing 2,197 percent and at the time of writing there were around 21,000 inmates serving from 20 years to life terms. The true madness of the situation is that re-imprisonment is estimated at between 55 percent and 95 percent. People are being recycled at huge cost through the prison system with no positive value to themselves or the country.

The wealth of data presented by Pinnock has resulted in a reference book that should be compulsory reading for every teacher, police officer, politician and municipal official. For parents and citizens of Cape Town it comes highly recommended too. It tells a story, but it’s also a valuable guide – solid as a rock; the majority of its arguments irrefutable. It drums home the reality that this is Cape Town, whether you live on the Cape Flats or the leafy suburbs. It’s a much-needed wake-up call, but also an essential handbook.

If you’re at all familiar with what lies beyond the postcard-perfect tourist hub at the centre of Cape Town, the contents may not surprise you. But dishing up the gory details was never the aim in any case – rather, Gang Town threads together the relevant, current information in a coherent and lucid form. Read it. DM

Become an Insider

Become an Insider