World

US 2016: Protectionism and the race for the White House

While Donald Trump’s increasingly violent, conflicted campaign rallies have taken up nearly all the oxygen in American politics in the past several days, the increasingly protectionist trade rhetoric in every candidate’s campaign has become an important, somewhat overlooked development. J BROOKS SPECTOR takes a look.

Right from the first years of the American republic, trade issues were a defining feature of American political debate. Once the nation had been freed from British colonial rule, it was, officially at least, now outside the British trading regimen and both its consumers and exporters now confronted British trade restrictions and export duties.

The country quickly became divided over trade issues — the more so because American tariffs were one of the few sources of federal government income, back before personal and corporate income taxes. In the American political system, per the constitution, Congress has sole power to set tariffs, subject to a presidential signature or veto. As a result, the country was soon divided into two very different camps and tariffs became a staple of congressional debate.

In the Northeast and New England, the burgeoning early days of industrialisation led its congressional representatives to push for protective tariffs against imports of much cheaper British manufactures. Meanwhile, in the newly settled western reaches of the country (in the lands from the Appalachian Mountains and on into the Mississippi Valley) as well as in the South, farmers were eager to import cheaper manufactured consumer products from England with little or no duties and, simultaneously, have better access to European markets for their cotton, tobacco, grain and other bulk agricultural products. These different interests reinforced the clash between advocates for protective tariffs against foreign manufacturers and those who just as fervently opposed them (and were simultaneously strong advocates for pressing foreign nations to lessen their duties on those primary commodity American exports).

As a result of such division, congressional debates over tariffs sometimes threatened the very stability of the nation, and it has even been argued that besides the great national agony over slavery, tariffs contributed to the sectional tensions that ultimately led to the Civil War. To a considerable degree, the orientation of the country’s national political system towards tariffs continued to split along a Northeastern and Midwestern versus Southern and Western axis, even as the country was growing into an industrial powerhouse.

Then, in the early stages of the Great Depression, in response to the growing economic pressures on American farmers from credit crunches, erosion and several years of poor harvests, the Republican Congress passed a major increase in American tariffs, the Smoot-Hawley Act. Even before the bill had become law, just the threat of its passage was provoking international threats of retaliation from trading partners.

As the bill made its way through Congress, foreign boycotts against American exports were being carried out, and foreign governments threatened to increase their own tariffs against the US. By September 1929, President Herbert Hoover’s administration had received protest notes over the pending tariff from 23 of the country’s larger trading partners. And, after the law went into effect, the country’s biggest trading partner, Canada, retaliated with its own new tariffs on about 16 products that represented nearly a third of total US exports to its northern neighbour.

According to the pre-eminent economic historian of the Great Depression and the former Federal Reserve Bank chair, Ben Bernanke, “Economists still agree that Smoot-Hawley and the ensuing tariff wars were highly counterproductive and contributed to the depth and length of the global Depression.”

Statistically, US imports decreased 66% from $4.4-billion in 1929 to $1.5-billion by 1933. Meanwhile, exports fell by 61%, and exports decreased 61% from $5.4-billion to $2.1-billion in the same period. Imports from Europe decreased from a 1929 high of $1.33-billion to just $390-million by 1932 and American exports to that continent went from $2.341-billion in 1929 to $784-million in 1932. Meanwhile, America’s GNP declined by nearly half in the same period and total world trade had decreased by around 66% between 1929 and 1934.

The post-World War II period led to a global rethink on tariffs, as a gradual movement built up for the general decrease in duties between nations as one crucial factor in increasing international trade, global wealth, and thereby international and the respective internal political stability of nations. Sometimes, progress on this has been easier than at other times — witness the prolonged agonies of the global trade negotiation rounds under the GATT/WTO umbrella.

An important moment for American trade liberalisation negotiations was passage of fast-track legislation back in 1974. Fast-track allowed a president’s administration to negotiate international trade agreements, such as tariff reductions, that could only be approved or rejected by Congress as a complete package. As a result, the measure would not be subject to any amendments on behalf of special interests eager to carve out or preserve a useful bit of protectionism for themselves via a sympathetic congressman or two.

Fast-track authority helped fuel moves for a wave of trade negotiations for the US, including the North American Free Trade Association (Nafta), and, most recently, the still-to-be-passed TransPacific Partnership. Until fairly recently, efforts towards free trade (especially given America’s competitive advantage in a range of products such as agricultural exports, aerospace products, entertainment, and financial services) had moved from partisanship to increasingly bipartisan support. Or as economist Paul Krugman wrote the other day, “Global trade agreements from the 1940s to the 1980s were used to bind democratic nations together during the Cold War, [and] Nafta was used to reward and encourage Mexican reformers.”

More and more, both Republicans and Democrats touted the benefits for bigger markets and — crucially for Africa — the idea that increasing duty-free access to the American market from Africa, i.e. AGOA, could be a more efficient, less costly way of encouraging economic growth on the continent and thus political stability in one tidy package than could ever come from foreign aid.

In theoretical terms, the underlying argument for free trade, harking back to Adam Smith and David Ricardo and absolute and comparative advantage in trade, is that it expands global well-being by reallocating capital and labour to activities where it can be used most productively. In a simple-minded example: Japan makes TV sets cheaply; Americans make cars cheaply; so, the two nations trade them and everyone ends up better off than before because when productivity rises, total production goes up accordingly. There is more wealth to spread around for everyone; everybody’s happy and thus the truth of Smith’s The Wealth of Nations is once again assured.

The devil comes in the details when it becomes clear that this now-expanded pie isn’t necessarily going to be distributed evenly. Free trade between a capital-rich country like the US and a labour-rich nation such as Mexico should increase the return to capital in the US and increase the return to labour in Mexico. Important, too, it can also lower the return to labour in the US and lower the return to capital in Mexico. That became a big ouch when some industrial plants moved from the US to Mexico after passage of Nafta, even as it increased demand for other American products by those now better off Mexicans.

Not surprisingly, American unions have been upset about free trade ever since the country began signing trade deals with developing countries such as Mexico. But the new electoral wrinkle this year is that the Republican candidates have been beating that drum even more than the labour unions that have been in the Democratic orbit for decades. (Some Democrats, of course, have been unhappy about deals like Nafta ever since the Clinton administration got that pact passed with Republican congressional votes.)

That bipartisan consensus that had been tilting towards free trade increasingly has now reversed course — in both parties — and with real implications for this year’s presidential election. This seems to have come from two sources. The first has been the overwhelming impact of economic globalisation that hit American manufacturing with a vengeance as country after country in East Asia became lower-cost alternatives to manufacturing in America for a wide range of products. Early on, it was Japan and the motor industry, but that has been followed by many other sectors such as textiles, home appliances, consumer electronic goods and apparel — and even new industries such as solar panels. Aside from all the economic dislocations from this wave of globalisation, the wave also generated a profound disruption and encouraged a rupturing of ties of loyalty for many southern white, working-class and ethnic Americans to the Democratic Party, reaching back to the Roosevelt era, who were the primary victims of these industrial upheavals and job losses.

That divorce was also pushed forward by the passage of the 1964 Civil Rights Act and the 1965 Voting Rights Act as a result of President Lyndon Johnson’s pressures on Congress in tandem with the civil rights revolution. The Republican Party first eagerly courted and embraced southerners, working-class whites and ethnic Americans in the 1968 presidential election, even though the GOP has never quite managed to integrate the values and interests of such voters with the older, more traditional GOP internationalist and business-oriented sectors of that party.

The GOP establishment managed to paper over those fundamental differences within their party for several decades. But, now, in the wake of the frustrations in the wake of globalisation, all of the candidates vying for their presidential nomination this year, save for John Kasich (to a modest degree), have been actively bringing together the anger over globalisation together with a generous dollop of anti-foreigner Tea Party-ism and a sub rosa pitch that the traditional Republican elite has failed to defend the needs of its supporters because the old elite’s class allegiances outweighed those of these “new” supporters.

Most successful of all at this, so far at least, has been an outrageous Donald Trump. He has created a virtually pitch-perfect, aggressively protectionist, foreigner-bashing rhetoric that also embraces a full-throated ridicule of a national political elite that has been too ineffectual to bargain on behalf of or defend the country properly. (About the only thing left out of such charges has been that this elite has been wilfully committing economic treason, rather than ineptitude. As his campaign becomes increasingly shrill, maybe that will be thrown into the mix as well, if it will help him.) And this comes along with those barely concealed racist appeals aimed at those angry at or fearful of the country’s changing demographics, in an effort to gain their support for him for the nomination. The likely success of such an ill-tempered, angry campaign may well make Trump the GOP standardbearer for the 8 November general election, unless lightning strikes the remaining Republican primaries – and most especially on Tuesday’s primaries.

Sensing electoral vulnerability — and not to be outdone in the media or in front of an increasingly angry electorate — the two Democratic candidates vying for their party’s nod, Bernie Sanders and Hillary Clinton, have also joined in the growing protectionist fervour. For Sanders, as an avowed Democratic-Socialist, his pitch has been an unabashedly class-defined argument. For him, it has been those evil bankers, the idle rich, and all those pernicious Wall Street finaglers who have so captured the political system that the legitimate needs of an electorate for real work at good wages in well-defended industries have been ignored.

Meanwhile, Hillary Clinton (as with John Kasich who was an influential, generally free-trade-supporting Republican congressman for close to two decades) cannot plausibly deny the historical bipartisan free trade agenda in its entirety or in its history without looking and sounding like she is denying her entire political heritage and being a flip-flopper of notable proportions. Clinton, after all, was Secretary of State when the TransPacific Partnership was being proposed and negotiated. As a result, both Clinton and Kasich have now been speaking increasingly about fair trade, rather than free trade (even as they have eschewed the racialised name-calling as a trade argument that is now a hallmark of the Trumpian rhetoric). Instead, they have highlighted a need to renegotiate any trade agreements that have foolishly given away the store without proper quid pro quos.

The problem, of course, is that this growing chorus of support for protectionism is not unique to America, and the infection may be spreading. As The Economist noted earlier this week, “The same forces roiling American and European politics are also present in most of Asia: internal ethnic and communal tensions; protectionist fears about globalisation and job losses; and angry, assertive nationalism. India’s prime minister, Narendra Modi, seems unwilling or unable to control the extreme Hindu-nationalist wing of his own party; Shinzo Abe in Japan is similarly loath to distance himself definitively from his party’s right-wing historical revisionists; China’s Xi Jinping is encouraging a resurgence of national pride which can take ugly, xenophobic forms. All three play variations of Mr Trump’s rallying cry: ‘Make our country great again!’ The rise of nationalism at a time of economic gloom and geostrategic uncertainty is alarming for the region’s security. Europe, preoccupied with its own problems, has long forsaken any serious role in Asia. Now some Asians worry that America, needed more than ever to balance China and ensure the long peace, will start looking the other way.”

No one is arguing yet that a 2016 version of Smoot-Hawley in America and retaliatory tariffs from other nations are in the offing. What is increasingly clear, however, is that regardless of who wins in this year’s presidential election, there may well be little impetus for new efforts towards freer trade. Instead, there may well be growing pressure for more pugnacious, harder-edged, less optimistic attention towards any free trade agenda. As a result, the trade lawyers will probably become busy pursuing lawsuits over violations of fair trade practices, almost regardless of who wins on 8 November 2016. DM

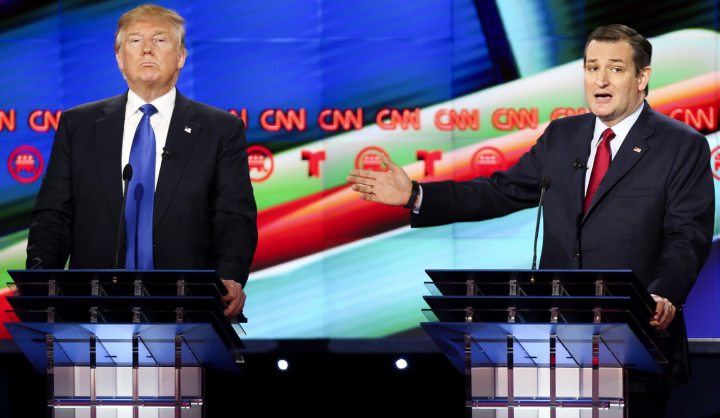

Photo: US Republican presidential candidates, Donald Trump (L) listens to Ted Cruz answering a question during the CNN Republican Presidential Primary Debate at the University of Houston’s Moores School of Music Opera House in Houston, Texas, USA, 25 February 2016. EPA/GARY CORONADO/POOL

Become an Insider

Become an Insider