World

US2016: What do the American Big Five really think about the untidy world beyond America?

If anybody wanted to know just how thoroughly the five remaining major candidates in the US presidential election have thought about the USA’s foreign challenges and how to deal with them, it still remains difficult to determine thus far. By J. BROOKS SPECTOR.

It is bizarrely fascinating that while the contest for the Democratic and Republican nominations for the American presidency has barely begun people have already been asking me what kind of foreign policy initiatives and changes would come about when any of the “big five” candidates – Clinton, Sanders, Rubio, Cruz and Trump – actually wins this election. Since one of these five is going to be the person who steps forward on 20 January 2017 to take the oath of office, it is worth a first look at this.

Photo: Democratic U.S. presidential candidates Senator Bernie Sanders and former Secretary of State Hillary Clinton discuss an issue at the Democratic presidential candidates debate at St. Anselm College in Manchester, New Hampshire December 19, 2015. REUTERS/Brian Snyder

So far, for the most part, foreign policy discussions by the respective candidates have had an almost cartoonish quality to them. These include: Islam bad. Islamic nations, still worse. Carpet-bomb Syria. Build a wall along the US-Mexico border. Slap a 45% duty on imports from China. Build up the Navy big time and make sure everyone knows it. Be strong, be resolute, be tough and be the biggest, baddest guy on the block. Or, as Steven Walt said in Foreign Policy the other day, “Rubio is a naive neocon. Everybody hates Ted. Hillary is a hawk. Bernie has bigger fish to fry. And who the hell knows how Trump would screw up the world.”

About the only candidate whose foreign policy thinking has been on serious display throughout this campaign so far is Hillary Clinton – and that is largely because she’s been at the centre of American foreign policy formulation for a major chunk of the Obama administration. Her words – and any evolution of her views – are firmly on the public record.

For the rest, it is still something of a roll of the dice.

Hillary Clinton’s views on foreign policy can sometimes have a malleable quality to them, such as her recent wobble about the Trans-Pacific Partnership, but generally, they are well known and rather consistently expressed. In that recent town hall meeting in Derry, New Hampshire, for example, when asked if she could pledge not to rely upon the military to solve international relations problems, she insisted that such a blanket pledge would be impossible to give, even though the use of military force should be the final choice rather than the first one and one reserved for specific, severe threats to the nation.

In fact, if elected, her foreign policy approaches would ultimately look a great deal like those of her predecessor. Many of the same implementers and advisors would undoubtedly be on the job, although her specific policies might well have a slightly more hawkish tinge to them than was the case with Obama’s. Observers say that if her advice had been followed in full during her tenure at Foggy Bottom, the country might well be more deeply engaged in Syria than is the case now, what with its generally “words only” approach towards Russian airstrikes in support of its client ruler there. Still, if a general sense of continuity is seen as good, a Clinton presidency is a safe bet for that outcome.

However, such an approach would also carry with it a continuing sense of the global essentialism of American power as it has been since 1945 and might yet draw the US into other seemingly intractable conflicts. If so, the general Clinton preference for continuity in foreign policy, but with a slight rachetting up from the more cautious Obama doctrine of “constrainment” might be a problematic one, given the rapidly changing distribution of power in the post-cold war world and most especially the shift in power towards a resurgent China.

Meanwhile, so far at least, Bernie Sanders has been waging his campaign – save for his frequent rejoinder that he voted against George W Bush’s war in Iraq while Clinton supported it – as far from any real engagement with foreign policy issues as it is possible to do. Instead, his pitch has been that he will lead a political revolution against evil banks and a perfidious Wall Street, in favour of a new health care dispensation, a higher minimum wage and a general absence of business as usual in domestic policymaking as he drums the money changers out of the policy making temple. Although Sanders hasn’t eschewed the use of force internationally in all cases for all time, any real sense of what he would do towards Asia, in Africa, about the global refugee crisis, in disputes with China or Russia all essentially remain mysteries kept in a locked box inside a bolted cupboard.

Curiously it can be argued Sanders has been taking a leaf from the 1992 Clinton campaign where the Big Dawg and his team argued the election was all about the economy, rather than any kind of substantial attention to a still-emerging post-cold war world, and that President George HW Bush just didn’t get it. Of course it still seems unlikely Sanders will ever get to try out his presumed alternative approach to foreign policy – or to decide about any expensive defence procurement programs in the coming decade such as the planned large-scale replacement naval vessels, those major cyber-warfare initiatives, and the proposed warhead replacement program.

Instead of detail, so far, the Sanders foreign policy vision, as in a statement at the end of December 2015, has been broad brush, such as: “The test of a great and powerful nation is not how many wars it can engage in, but how it can resolve international conflicts in a peaceful manner. I will move away from a policy of unilateral military action and regime change, and toward a policy of emphasizing diplomacy, and ensuring the decision to go to war is a last resort.” Now who can really argue with this?

Still, the primaries and caucuses that come along on the first, eighth and fifteenth of March will likely inform the country if Sanders really is still in the race, or he has, ultimately, just been a brief flowering of enthusiasm for someone other than Hillary Clinton and her pragmatic business as usual approach to an untidy world.

Meanwhile over in the other playpen, the remaining combatants now appear to be the trio of Marco Rubio, Ted Cruz and Donald Trump. For the sake of simplicity, we can dispense with consideration of the remaining minor candidates like Jeb Bush, Chris Christie, John Kasich and Carly Fiorina. So, let’s take them in reverse order.

Rather than being able to operate under the mask of being an internationalist neo-conservative or even international realist, it seems fair to put it on the table that Donald Trump is really just a nativist populist, paired with some plain vanilla xenophobia. Neo-conservative foreign policy advocates argue for clearly articulated policies that take the fight to opponents, while the international realist position argues for a clearly defined strategy that avoids unduly picking fights and in recognizing that even a strong nation must work with others in the international environment. Real realism in foreign policy is not opposed to a well-established, well-regulated global trading order; and does not propose punitive public works projects like a massive wall along the Rio Grande River. Nor does it give vent to intemperate rants against a billion or so Muslims and the proposing of religiously targeted entry restrictions into the country – if for no other reason than such lurid fantasies guarantee creating enemies out of potential allies.

Instead, consider a recent statement by Trump in which he argued, “I will… quickly and decisively bomb the hell out of ISIS, will rebuild our military and make it so strong no one — and I mean, no one — will mess with us.” Or perhaps take on board his diatribe about China, arguing, “China is bilking us for hundreds of billions of dollars by manipulating and devaluing its currency. Despite all the happy talk in Washington, the Chinese leaders are not our friends. I’ve been criticized for calling them our enemy. But what else do you call the people who are destroying your children’s and grandchildren’s future? What name would you prefer me to use for the people who are hell bent on bankrupting our nation, stealing our jobs, who spy on us to steal our technology, who are undermining our currency, and who are ruining our way of life? To my mind, that’s an enemy. If we’re going to make America number one again, we’ve got to have a president who knows how to get tough with China, how to out-negotiate the Chinese, and how to keep them from screwing us at every turn.”

But perhaps the real problem is that Trump’s pronouncements have been so oafish and cartoonish it almost impossible to evaluate what his real positions on actual issues are. Thus the real worry is that no one can have a clear idea what Trump’s foreign policy would be – or any way be able to predict just how he might react in a crisis, other than with lots of bluster and chest beating. Does anybody know what he has read about global issues, whom he listens to or if he has any rich understanding of the way foreign policy is designed, articulated and implemented. The man is a virtual foreign policy tabula rasa. And who would rally to his banner to serve in a Trump administration if he actually were elected – unless he expected he would negotiate every international agreement or accord all by himself and dispense with the need for anybody else.

Then there is Ted Cruz. If some of his statements are to be believed, he will be the final word in a style of unilateralism virtually gone amuck. In a phrase too good not to quote, Winston Churchill, in a phrase he applied to Eisenhower’s secretary of state, John Foster Dulles, Cruz is “a bull that carries his own china [shop] with him.” In fact, in Cruz’s campaign material so far, the candidate’s views are in favour of strength and opposed to that supposed Obama-esque “weakness”; support for a strong national defence; and opposition to immigration – in essence, the usual suspects of the Republican right-wing. As a bonus, Cruz has repeatedly promised to tear up the Iran nuclear agreement (yup, the one painfully negotiated by six powers, working in tandem, in dealing with Iran and now verified by the IAEA) in his very first day in office. And as a modest lagniappe to it all, he has advocated a quick solution to the Syrian disaster by carpet-bombing the entire place, perhaps in competition with Vladimir Putin’s air force? And as for his foreign policy advisors, so far at least, his chief sidekick apparently has a degree in art history. Who would rally to his call for government service is thus something of a mystery as well.

And finally we come to Marco Rubio. At least his international frame of reference is reasonably identifiable. Colour him a rather traditional neo-conservative internationalist (with the financial and intellectual support backing this up in the persons of mega-rich guy Sheldon Adelson, and the New York Times’ favourite house conservative, David Brooks respectively), along with some added spice in his insistence the second Iraq invasion was the right thing to have done. In his campaign and debate appearances, Rubio has repeatedly hammered away at the supposed weakness of the American military, citing the decline in ship numbers from the peak numbers at the height of the cold war (or World War II), despite the massive increase in the firepower of nuclear-armed subs and the country’s baker’s dozen or so of nuclear powered carriers always on station. The Rubio prescription for China is to smack it for human rights abuses, but continue to maintain trade, even as he hopes to support the TransPacific Trade Partnership to counterbalance Chinese trade. As Waltz in Foreign Policy acidly observed, “In short, a Rubio presidency would confirm that the United States has learned precisely nothing from its tragic experiment with neo-conservatism [as in the example of George W Bush]. If that’s where we end up this November, we’ll deserve whatever punishment history decides to dish out.”

The truth, of course, is that whatever a candidate says he or she will do, reality usually intrudes, the bureaucracy and a vast horde of special interests (ranging from trade bodies to human rights NGOs) have their say and chivvy initiatives this way and that. And, of course, all those other nations and leaders will do what they will do – sometimes without regard to what a new president has said. But a leader can still make a difference in the tone of a country’s external policies, in the way a leader can give voice and hope to those who strive for a better, fairer, less brutal world, and in the way the nation they lead engages and leads others to achieve a more peaceful, economically vibrant world. And, of course, a president will sometimes be called upon to step forward to help nations prevail against global economic turmoil if it should come.

As the campaign progresses, the respective candidates will articulate a more cogent set of international relations policy proposals – and just as certainly their ideas will be interrogated by the media and by the others’ campaigns. And just maybe the foreign policy debate in this electoral cycle will move beyond the cartoon version where candidates sound like those words printed above the characters in a superhero comic book. DM

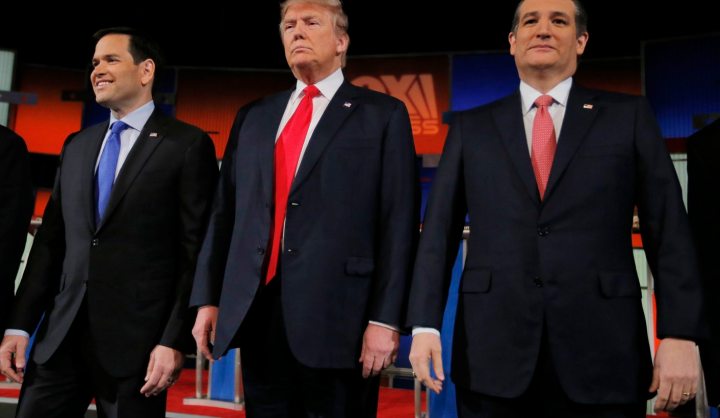

Main photo: Republican U.S. presidential candidates (L-R) Senator Marco Rubio, businessman Donald Trump and Senator Ted Cruz pose together before the start of the Fox Business Network Republican presidential candidates debate in North Charleston, South Carolina January 14, 2016. REUTERS/Chris Keane

Become an Insider

Become an Insider