World

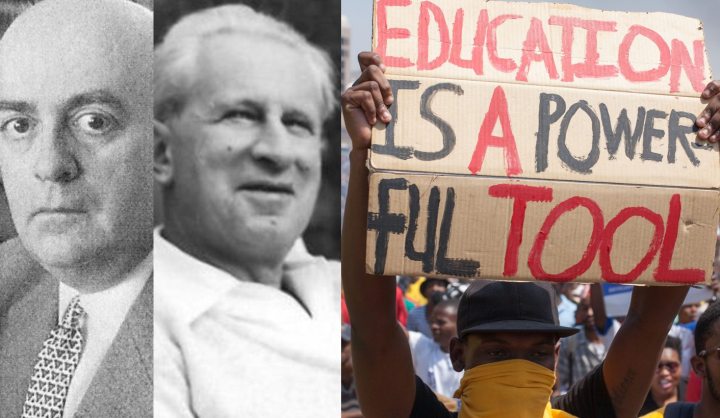

Theodor Adorno vs Herbert Marcuse on student protests, violence and democracy

Below is an excerpt from “Diary of My South African Years”. The “Diary” includes various notes, fragments, unfinished texts (some of them hand written), public interventions, interviews and other material accumulated over many years. The excerpt published here was written last year. It is not a formal analysis of current events. It is an exercise in sympathetic critique, a tradition of reading one’s own times that is much rooted in various versions of Black and Jewish thought. By ACHILLE MBEMBE.

South Africa, October-November 2015. This is not May ‘68. This is neither France, nor Germany or the United States of America. And yet, since the current wave of students protests began – the most significant since Soweto ‘76 – I have returned countless times to the debate that opposed Theodor Adorno to Herbert Marcuse in 1969, as the Western world was engulfed in arguably the most significant student turmoil of the 20th century.

I have returned to these most eminent Jewish-German thinkers not so much because they have anything to tell us about our own predicament here and now (how to undo the legacies of settler colonialism in the conditions of the 21st century and what is the role of violence in that process), but because each in his own way, as well as in a direct and respectful confrontation with each other tried – through critique or what they called theory – to bear witness to the main events of their time.

We are called upon to do the same for our own times. Obviously, we have to find for ourselves the vocabulary to name the ongoing student turmoil in South Africa and to decipher what is ultimately at stake in these events, what they tell us about our own moment and, more importantly, the generative possibilities they might harbour, their ambiguities and profound ironies, or the unintended culs-de-sac they might eventually lead to. In this necessary task of naming and elucidation, what is required is the kind of sympathetic critique that amounts neither to endless praise singing, nor to unconditional alignment with political causes whose full consequences are yet to be known.

Left fascism

Marcuse followed the German version of the student uprising from Southern California, where he had been teaching. He did not believe that the student movement in itself was a “revolutionary” force. He nevertheless thought of it as “the strongest, perhaps the only, catalyst for the internal collapse of [capitalism], its henchmen in the Third World, its culture and its morality. Although not naïve about the prosaics of the movement (its own methods, its own ambiguous relationship to violence and cruelty, infiltrated as it was by all kinds of provocateurs), he was willing to believe that it had the prospect of effecting a social intervention. On this basis, he was willing to be blind to its shortcomings and ironies, preferring to see these shortcomings and ironies as part of a broader search for forms of organisation that could effectively disrupt late capitalist society’s dominant logics.

His analysis was strongly influenced by events unfolding in the United States – the development of political consciousness among the students, the agitation in the ghettos and the assertion of black nationalism, the alienation from the system of layers who were formerly integrated, the mobilisation of further circles of the populace against American imperialism in Vietnam and in the rest of the world.

Adorno, for his part, had been a direct target and a recipient of some of the student rage. A room at the fledging Institute of Social Research (of which Adorno was the Director) had been occupied by students who had then refused to leave despite three requests. The Institute – probably Adorno himself – called the police who then arrested all those they found in the room. According to Adorno, no physical force was used. The police, he later argued, treated the students far more leniently than the students had treated him. Now, the students were nevertheless asking that Adorno “humbles himself” and carries out “public self-criticism”, something he regarded as “pure Stalinism”. Adorno did not underestimate the merits of the student movement. He recognised that it had interrupted what, until then, had mostly looked like a smooth “transition to a “totally administered world”. He nevertheless doubted the student protest movement had even the tiniest prospect of effecting a social intervention in the Germany of his times. In fact, he thought it could only inflame a fascist potential that remained undiminished in post-war Germany.

Not only did the movement “not even care about fascism”, it bred in itself tendencies “which directly converged with fascism” – its sectarian nature and its quasi-millenarian propensities; its willingness to at times embrace brutality as an ordinary mode of politics; its constant fudging of the question of ends and means; its perennial scapegoating of those who opposed it; its tendency to vilify and to demonise those it perceived as its enemies; its propensity “ to destroy” rather than “ to create”. Because of this mixture of “a drama of madness” and “brutal practicism”, Adorno was convinced it harboured the seeds of “totalitarianism” – if only teleologically.

Just as Marcuse loathed capitalism and was willing – at the risk of mauvaise foi (bad faith) – to support any movement no matter its form and content, provided it declared its opposition to capitalism, Adorno’s arch-enemy was fascism whose return in the guise of leftist and pseudo-radical logorrhea he dreaded. For him, permanent disruption was but an unscrupulous way of “performing radicalism”.

“I take much more seriously than you the danger of the student movement flipping over into fascism,” he told Marcuse.

Ends and means

Symptomatic of this risk of flipping over into fascism were a set of rituals and practices Adorno particularly abhorred – for instance, the technique of calling for a discussion, only to then make one impossible; “democratism” in the form of endless, and at times fruitless committee meetings; suspicion and paranoia, especially in relation to questions of leadership and representation; a mode of behaviour (he qualified it as barbaric inhumanity) that confused “regression” with “revolution”; the blind primacy of “direct action” as a substitute for “thought”; a formalism and proceduralism which were indifferent to the content and shape of that against which one revolts. For him, dialectics meant, amongst other things, that ends were not indifferent to means.

A lot of what the students had done smacked of callousness and expediency, he suggested. For instance, they had organised the occupation of a room at Adorno’s Institute (a stunt, he called it) precisely in order to get taken into custody, and thereby hold together a group that was well in a process of disintegration.

“What is going on here drastically demonstrates, right down to the smallest details, such as the bureaucratic clinging to agendas, ‘binding decisions’, countless committees and suchlike, the features of just such a technocratisation that they [the students] claim they want to oppose, and which we actually oppose”, he wrote.

But even more damning, the old man who in his attachment to the Ninth Symphony had described “Jazz and Beat” as “the scum of the culture industry” could not but suspect the student movement of exhibiting latent anti-semitic tendencies. Hadn’t the movement “shouted down” the Israeli Ambassador in Frankfurt?

Adorno and Marcuse had markedly different views of the student movement because of their divergent understandings of the relation between theory and praxis, the limits and possibilities of democracy under late capitalism, the morality of the violence of the oppressed, the place of violence in struggles for deep democracy, the relationship between security and freedom and countless other issues.

For Marcuse, even “the most intact theory” was not “immune” to the effects of reality. It was wrong, he admitted, to negate the difference between theory and reality. But it was similarly wrong to “cling onto the difference abstractly”. Reality, for him, embraced theory and practice. He rejected any unmediated politicisation of theory. But he was adamant that theory (especially of the kind the Frankfurt School did in the 1930s, of which he was nostalgic) had an internal political content, an internal political dynamic that might compel its author, under specific circumstances, to concrete political positions.

One such concrete political position had to do with the occupation of university buildings: “I believe that in certain situations, occupation of buildings and disruption of lectures are legitimate forms of political protest,” especially if such actions are a response to the brutal breaking up of student demonstrations. Another related to the police. Marcuse agreed the police should not be ‘abstractly demonised’. He even admitted that he, too, would call the police “in certain situations”.

First and in reference to the university – “if there is a real threat of physical injury to persons, and of the destruction of material and facilities serving the educational function of the university”.

Second, and in reference to his life, his property and those of his friends – “if my life is threatened or if violence is threatened against my person and my friends, and that threat is a serious one”.

Otherwise, “occupation of rooms (apart from my own apartment) without such a threat of violence would not be a reason for me to call the police”.

In any case, “if the alternative is police or left-wing students, then I am with the students,” he concluded.

Violence, protest and democracy

Marcuse was not only opposed to capitalism. He was also highly critical of democracy. Democracy “grants us freedoms and rights”, he conceded. He nevertheless considered democracy as the quintessential form of domination under late capitalism. For him the choice was not between democracy and neo-fascism. Capitalist democracy, in line with its inherent dynamics, “drives towards a régime of force”. Would capitalist democracy collapse, its collapse might well bring about a dictatorship. But such a dictatorship, he thought, would not be worse “than what exists”. Given the “degree to which bourgeois democracy seals itself off from qualitative change”, extra-parliamentary opposition (civil disobedience, direct action) becomes “the only possible form of contestation”.

Marcuse found all kinds of excuses to the illiberal, and at times brutal aspects of the student movement. The brutality students could deploy and the “fight with knives in a tunnel” model some of them advocated were “nothing compared to that over which the rulers dispose”, he argued.

“The use of force, the practitioners of violence, all that is on the other side, in the opponents’ camp, and we should be wary of taking over its categories and using them to label the protest movement”, he cautioned. “We cannot identify the violence of liberation with the violence of repression, all subsumed under the general category of dictatorship”, he concluded.

The “holier-than-you” dilemma

Both Adorno and Marcuse, each in his own way, devoted intelligence and attention to the potential of their own times. Adorno was not only alert to the ugliness of the system they both opposed (the total administered society). He was also aware of the distinct possibility of a self-declared and self-anointed moral revolt mutating into a fascism of the left. He was right to believe that there were moments in which theory was pushed on further by practice, but wrong in thinking that such situation did not obtain in 1969.

Marcuse was wrong in finding all kinds of excuses to the politics of brutal practicism. Under the pretext that “the defence and maintenance of the status quo and its cost in human life is much more terrible” than the brutality of the oppressed, brutal practicism romanticized violence and justified the violation of other people’s rights by self-anointed moral crusaders. Marcuse was right to oppose the slogan “destroy the university” – then popularised by fringes of the student movement – which he regarded as a suicidal act. Both Adorno and Marcuse were wrong in their predictions.

The student movement did not flip over into fascism as Adorno feared. But it did not destroy capitalism as Marcuse hoped it would. If anything, it emboldened it. Student protests, even when undertaken in the name of freedom and equality, were not immune to the law of unintended consequences. Adorno was right to wonder whether a movement bent on performing radicalism rather than actually enacting it could transform itself into its opposite by the force of its immanent antinomies. Marcuse was wrong to assume that what he called the (authentic) left could not mutate into the Right or, through sheer expediency, tactically ally itself with the most reactionary forces of the moment.

Finally, they both failed to adequately deal with the security-freedom conundrum. Not all security arrangements are by definition inimical to freedom. Like violence itself, they always breed ambiguity. Freedom in and of itself does not automatically guarantee security. Each of these terms needs to be supplemented. To supplement freedom and to supplement security, neither angelism nor callousness will suffice.

Ethical pragmatism – a pragmatism that is opened to its ethical core being constantly contested – will take us a long way. But in the end, it will not resolve the conundrum once and for all. We will therefore have to learn to live with irresolution. Momentous events are times when new alliances are crafted when old ones crumble. Coalitions are built, disassembled and reassembled. In the process, some bridges are irrevocably burnt. Old friendships are reaffirmed or simply thrown out of the window. Will we have the time to mourn these losses? DM

Photo: Theodor Adorno, Herbert Marcuse (Wikimedia Commons), Student protest turning violent in front of the Union Buildings 23 November 2015 (Photo by Greg Nicolson)

Become an Insider

Become an Insider