South Africa

Op-Ed: The real indictment of Thabo Mbeki

Thabo Mbeki has a first-rate intellect and a second-rate temperament. His legacy is felt throughout government, and in the president he bequeathed us. Just as he failed to groom a set of next-generation leaders at the top, he discouraged original thought, and rewarded blind loyalty at lower levels. By JOHN MATISONN.

The story so far: Eight years after leaving office, Thabo Mbeki has begun a series of essays telling us what he has learnt. As the country faces its deepest crisis since 1994, and institutional memory is most needed, Mbeki writes his first piece. He argues that he was not driven by personal grudges. He devotes his second essay to excoriating a political enemy from 13 years ago, indicating that grudges are exactly what still animates him. Instead of introspection about his, or our, possible mistakes, his second missive attacks Jeremy Cronin, a Deputy Minister in the present government.

In his first article, Mbeki makes it clear he is challenging the false accusation that he was governed by paranoia. In his second, the former president’s most telling line on this Deputy Minister’s criticism in 2002 is: “For whose benefit did (Cronin) find it necessary to communicate fabrications about the functioning of the ANC NEC?”

Dare I say this sounds paranoid? Mbeki has not chosen to reveal what he has learnt from his presidency. What should we learn? Mbeki’s mistakes on AIDS and Zimbabwe need no repetition. They are well-known. But they point to a deeper indictment. South Africa has universities that produce experts, and an excellent medical tradition. Why were his policies not guided by the best scholars, by the many places where South African civil society could fill in the gaps in the ANC’s experience? What, since he left government, has he learnt that could help us avoid repeating these mistakes?

He inherited from Mandela a rich bench of leaders and a clear succession. The one he left was denuded. What the “plot” scenario had done was destroy that bench. So, the importance of that moment now is not who used what words; it is that he failed to provide an orderly succession, and arguably prevented it. That is what has led us into the mess we’re in. Jacob Zuma got to the top because Mbeki made him Deputy President. Why would a president widely considered an academic snob appoint the least qualified man in the room? With an ANC full of lawyers, doctors, and post-graduate degrees, was he the best qualified? If not, why not?

Mbeki could have chosen from the deep bench of South African leaders visible after 1994. He could have helped the best of them get the experience in government we so sorely lacked, so that the country would be in safe hands when he left. This is where he failed. It was part of a bigger failure. What made him reject intellects that did not kowtow? Why did he think he would teach them, not learn from them?

An intellectual, Mbeki ran an anti-intellectual government. That’s why there was not that much difference when Zuma, the anti-intellectual, took over. He didn’t want strong intellects any more than Mbeki did! Jacob Zuma simply used his predecessor’s formula, recruiting by loyalty and subservience, not competence and originality. The result was a series of gigantic mistakes.

There was so much goodwill around the world for South Africa, so many people only wanting to help, with or without recognition. Madiba understood that. Recent efforts to portray him as this kindly old man who trusted everyone are far from the mark. He was tough, and he was a strategic thinker; he understood that he could get the best out of people without expressing his darkest fears of them.

What are the lessons of the Mbeki era? Why did Mbeki’s commitment to an Information Economy fail? Why are we bottom of African rankings on many educational scales? These are the questions we needed to answer. Why did we miss the dotcom boom? Why did we miss the resource boom? We were extremely well equipped to ride both, so that when they ended, we would have had investments to outlast a fall in commodity prices.

We need to engage in real debate, not vague and sarcastic pontifications from on high, but specific assessments of both successes and failures. Mbeki was right about Iraq, and he could usefully tell that story. And yet he was wrong about Zimbabwe. Why?

Madiba will live forever in our history despite the ups and downs of criticisms. Mbeki will be credited for specific successes where they are deserved, and there are some. But he will be remembered as the brightest man in the class who could not understand why everybody didn’t accept he should be school prefect. In short, as the man who would not listen, no matter the distinction of the expert would-be adviser. That, just as much as the successor he unintentionally bequeathed us, is the legacy South Africa confronts, and must overcome if we are to avoid a ratings downgrade, decade long social unrest and economic suffering by the poor while we figure out that we need the best, all those people whose distinction should not inhibit, but trump, their lack of subservience.

It was said of United States President Franklin D Roosevelt that he had a second class intellect, but a first class temperament, and in that lay his greatness. In Mbeki’s case the problem was the reverse; a first-rate intellect with second-rate temperament.

His legacy is felt throughout government. Just as he failed to groom a set of next-generation leaders at the top, he discouraged original thought, and rewarded blind loyalty at lower levels. Each of the trade unionists and Communist Party leaders brought to Cabinet were immediately compromised politically, being required to lead the charge for free trade and privatisation. The constituencies that got them there evaporated. They could never go back. Mbeki had rendered them politically impotent. When they left government they went into business for two reasons. First, clearly they did not mind being rich. But the second reason was that they had nowhere to go back to.

Overnight, they lost the support of the constituencies that sent them there. It is impossible to believe this was an accident that Mbeki did not anticipate. To believe he did not expect this assumes his intellect was second rate, and it was not.

These days, South Africans no longer expect the best people to get to the top. If they did, we would all assume that Professor Jonathan Jansen must be in line for Education Minister, Thuli Madonsela for Justice Minister, perhaps a business figure for Minister of Public Enterprises. Each would take office knowing what these complex jobs require.

That leads to the real indictment of Mbeki. Clearly, his mishandling of colleagues Cyril Ramaphosa, Tokyo Sexwale and Mathews Phosa was poor judgement, the result of a temperament that should have nipped a nonsensical intelligence report against them in the bud. Nobody in senior ANC ranks thought it credible. Coming from a compromised source, it should have been buried discretely, perhaps after some checking, if there was really anything substantive to check. Even if Mbeki’s contested version is to be believed, it was poor judgement. But given his propensity to reward weakness and loyalty over strength and originality, all the signs fit the narrative that he was removing potential rivals or successors. Little wonder, then, that faced with the choice of putting his fate in Mbeki’s hands, Ramaphosa chose to leave government after completing his work on the Constitution and build an independent financial base so he would never be dependent on Mbeki for his livelihood.

When I left my much less august role in government, without a pension, I had my own reasons to feel badly treated. But when I sat down to reflect on it for public consumption, I was trying to answer questions of governance. South Africa’s poor have needs that we could not fulfil. We made compromises, set priorities. Were our decisions right? What could we do better? What lessons can we pass on so. that the next generation need not relearn from scratch? Institutional memory is invaluable.

I lived on my savings and read and thought and wrote. I concluded, for example, that we South Africans spend too much time talking about the big picture. Half the country wants everything nationalised, the other half is just as certain it must be privatised. My experience in government taught me the answer: it depends. Public radio in the less spoken of the 11 official languages must be subsidised, because advertising will never cover it. On the other hand, the private sector regulator by an independent public watchdog is the best way to build our failing Information Economy. I put it all in my book, and people are free to tell me how wrong I am. But I can assure readers, it was the best advice I could give.

Unashamedly, my model of what a former public servant should do was Nelson Mandela. He mostly kept quiet, but he was always concerned with the future, not the past, and when he saw serious mistakes, like Mbeki’s AIDS policy, he found a way to call for a change of course, even if it made him unpopular.

Imagine what Mbeki could have done in his post-government life, if he applied his mind to nothing more than the common good. DM

John Matisonn is the author of GOD, SPIES AND LIES, Finding South Africa’s future through its past.

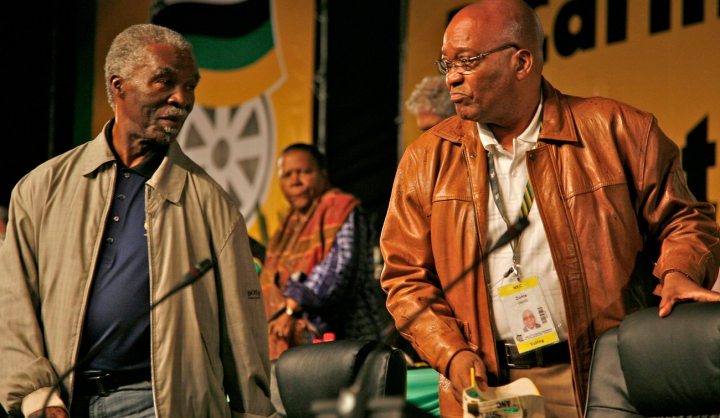

Photo: The ANC’s 52 conference – former deputy Jacob Zuma is announced as having won the election for party president by some 824 votes against incumbent Thabo Mbeki, Polokwane, South Africa, 18 Dec 2007. Photographer: Greg Marinovich.

Become an Insider

Become an Insider