World

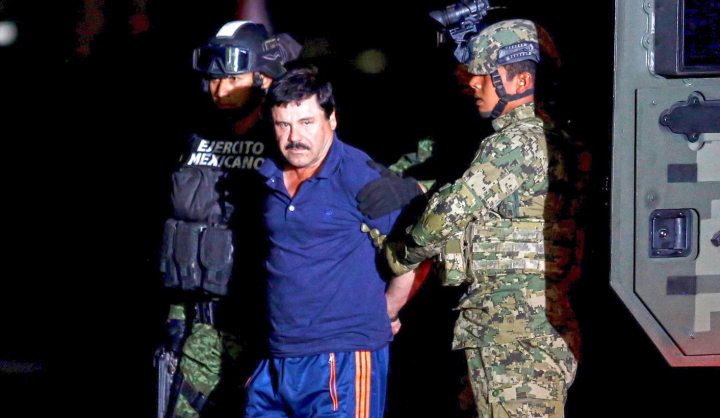

El Chapo arrested, again: Is Mexico getting a grip?

The Mexican public remain deeply sceptical about the state, and its ability stamp out drug-related crime and violence in the country. An estimated 63% of people surveyed said Joaquín Guzmán Loera’s own mistakes led to his re-arrest, only 29% believed that the state should take credit for the arrest. In general, most of the population have not changed their view of the government, and have almost no confidence in security forces. By MARY SPECK for the INTERNATIONAL CRISIS GROUP.

First published by the International Crisis Group.

The story of Mexican drug lord Joaquín Guzmán Loera – better known as “El Chapo” or “Shorty” – has all the elements of a Hollywood drama: humble beginnings to enormous wealth, business genius combined with cold-blooded cruelty, high-security prison escapes, culminating in a months-long manhunt, a gunbattle that killed five of his bodyguards, a desperate attempt to escape through a sewer, a carjacking, and then arrest by the Mexican marines.

But capturing another drugs kingpin does not solve Mexico’s security crisis, nor does it dent the international drug trade. Narcotics trafficking – and its many auxiliary enterprises, such as migrant smuggling, stealing petroleum, illegal logging, kidnapping, extortion – will continue to flourish, with or without El Chapo. Guzmán’s re-arrest on 8 January may have little or no impact on the Sinaloa cartel’s status as the world’s largest transnational drug organisation. ??

In order to address Mexico’s severe violence, President Enrique Peña Nieto’s Government must speed up its efforts to strengthen justice. The president’s proposal for major police reform should re-examine its strategy for “unified commands,” devising an integrated program to make local law enforcement more professional and accountable, and evaluate and reboot its violence prevention strategy, especially programs aimed at disadvantaged youth. Only then can the president repeat in good conscience his words after El Chapo’s capture: “Mission accomplished”.

Behind the Myth of El Chapo

It seems that Guzmán, nearly 60 years old, got entangled in his own life story. His attempts to produce his own biopic left a trail that led to his recapture. He got sloppy and cocky, confident that he could outwit authorities and eager to live up to his own myth. But El Chapo himself is no Robin Hood. His Sinaloa cartel is one of the last big drug trafficking organisations in Mexico. Like many of rival bands (the Zetas, the Beltran-Leyva clan, the Juarez cartel), Guzmán’s hitmen have much blood on their hands. Behind the El Chapo drama are some sordid realities in Mexico. Over the past nine years, tens of thousands have died from drug-related violence in the country, many never identified. There are an estimated 26,000 missing persons in Mexico, some of whom may have been dumped in the clandestine graves found in states like Guerrero, Tamaulipas or Chihuahua. The manhunt for El Chapo was in itself violent, with hundreds of people forced to flee their homes as Mexican troops stormed through towns and villages in the northwestern states of Durango and El Chapo’s home territory of Sinaloa.

Guzmán is now back at the Altiplano prison, kept in solitary confinement within a supposedly tunnel-proof cell with steel-reinforced concrete flooring. “My holidays are over,” he reportedly said on his arrest.

Peña Nieto’s Attempts to Fight Organised Crime

Mexican officials seem committed to extraditing him to the US, where he faces charges of smuggling vast amounts of drugs into the country. But do not expect the Mexican government to hand him over any time soon. Extradition could take months, with lawyers filing multiple petitions for constitutional protection (known as amparos), each of which requires a court hearing. Getting Guzmán is a “moral victory”, according to a former US counter-narcotics official, and a boost for Peña Nieto, even though it will not blot the embarrassment of his brazen prison break in July along a mile-long tunnel after 16 months in his maximum security jail.

A poll taken by La Reforma shortly after the recapture reveals a public that remains deeply skeptical. 63% of those surveyed said Guzmán’s mistakes led to his re-arrest; only 29% credited the authorities. Most said their view of the government remained the same or worse (73%). Confidence in security forces is also low, which suggests that police reforms will not restore trust without concerted efforts to purge and professionalise law enforcement at all levels.

This is not all the president’s fault. In the past, Mexican authorities have nabbed or killed dozens of drug bosses, without significantly reducing the drug trade despite decapitating criminal organisations as notorious as the Zetas, the Knights Templars, the Juárez and Gulf cartels. Peña Nieto took office in 2012 determined to distance himself from his predecessor Felipe Calderón, who waged war on the drug cartels in close collaboration with the US. He was more interested in pushing through an ambitious program to spur the economy, including measures to privatise the state-run oil industry, break up telecommunication monopolies and improve education. The linchpin of his security policy was supposed to be violence prevention and citizen participation, based on social programs in vulnerable communities, including promising experiments in cities such as Ciudad Juárez. The national crime prevention program is now in disarray, however, following budget cuts and the resignation of the undersecretary in charge to face accusations of electoral irregularities.

Much of Peña Nieto’s November 2014 security plan – including the proposal to merge municipal and state forces into “unified commands” – has stalled in the face of opposition or indifference on the part of Congress, the governors and local authorities. The country is in the midst of a sweeping justice system reform, changing federal and state courts from an inquisitorial to an adversarial system, which is scheduled for completion in 2016, though many states are unlikely to meet the deadline.

Strengthen Institutions

Authorities have demonstrated their ability to capture or kill top mafiosos, but they have not shown they can investigate mob-related crimes, convict the perpetrators and then keep them in jail. No country should have to send in the marines to catch a mobster. In areas where the criminals have penetrated local police or municipal governments – and where gangs routinely charge shopkeepers, public employees, workers and even street vendors for “protection” – citizens face little choice; remain a victim or become a perp.

For youths without a decent education or marketable skills, dealing drugs, working as lookouts, bagmen or even sicarios (a hitman) may seem the only way to get ahead and win respect. In rural areas of Guerrero, Michoacán, Sinaloa and other states, growing opium poppies, farming marijuana or operating a meth lab, may seem the best way to feed a family.

Controversy surrounds the investigation into the September 2014 disappearance of 43 college students in Ayotzinapa in Guerrero state, blamed on police allegedly acting in league with gangsters. Despite the deployment of federal police and soldiers, Guerrero suffers from the country’s highest – and rising – homicide rates. Meanwhile, human rights groups are demanding further investigation into the killing of 42 alleged traffickers by federal police in Tanhuato, Michoacán, and of 22 suspected kidnappers by soldiers in Tlatlaya, Mexico state. The potential rewards of crime outweigh the risk of capture or conviction. Only a fraction of Mexico’s homicides, to cite only the most notorious crime, are investigated, much less solved.

Given the strength of organised crime and the weakness of Mexican institutions, President Peña Nieto and his counterparts at the state and local levels need to understand that the arrest of leaders alone is unlikely to significantly weaken organised crime. In the long run, it will be much more important to develop police forces and a justice system capable of enforcing law and order. DM

Photo: Joaquin “El Chapo” Guzman is escorted by soldiers during a presentation in Mexico City, January 8, 2016. REUTERS/Tomas Bravo.

Become an Insider

Become an Insider