Maverick Life

Remembering the Unforgettable Ch-ch-changes

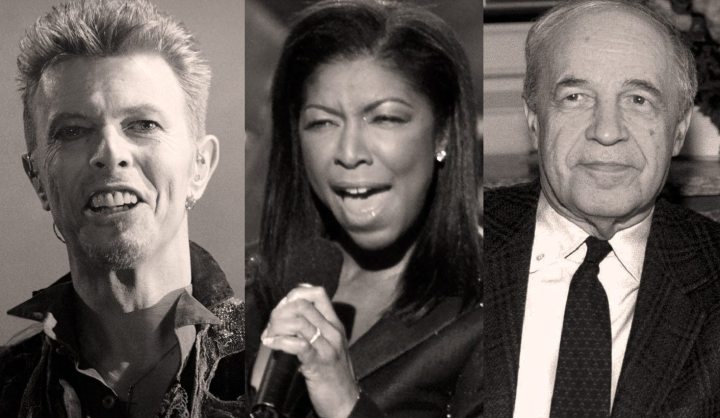

J. BROOKS SPECTOR considers the place of a trio of truly irreplaceable musicians who have departed this world in just the past two weeks.

Over thirty years ago, the author first watched the most astonishing UK-Japanese cinematic co-production, Merry Christmas Mister Lawrence, that starred musician David Bowie studded in the midst of a cast of A-list Japanese actors. Bowie had inhabited his part, taking on the essential character of a British Army officer who had become a POW during World War II in a prison camp in Japanese occupied Java, as his character offered subtle resistance to the very idea of being a POW. The story was derived from a book by Laurens van der Post.

Watching that film and Bowie’s almost effortless acting, it was easy to forget Bowie was already a global cultural figure, and an influence on such musicians as Michael Jackson. Bowie’s impacts ranged from his transformative role as a rock musician (including setting off the explosion that became the glam rock phenomenon), and on to his place as a fashion, style and social trendsetter. He was the man who literally dragged the idea of “androgynous” into public repute and, over his lifetime, he transformed what was his already iconic, but constantly evolving performing status into something very different. He turned himself into a style, a kind of unique public performance art of being David Bowie. But even without some of the performances and the music, it was that Bowie face: those impossibly smooth facial planes; his mysterious eyes of two different colours; the unfailingly stylish hair; and even the makeup that all seemed to say, “Follow me on into the future where everything will be… different.”

Perhaps impossible to pin down precisely, over a decade ago Bowie had said about life, death, and pretty much everything in between, that “What I’ve learned, I’m in awe of the universe, but I don’t necessarily believe there’s an intelligence or agent behind it. I do have a passion for the visual in religious rituals, though, even though they may be completely empty and bereft of substance. The incense is powerful and provocative, whether Buddhist or Catholic.”

At the time of his death on 10 January 2016, Bowie had over two dozen albums to his credit, including “Blackstar,” the album released just days before he died and that – in retrospect at least – seems to have been created as an aural farewell to friends and fans. Throughout his career, many of Bowie’s works revealed his continuing fascination with space exploration and travel, such as his early 1972 album, “The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders from Mars”. The irrepressible Canadian astronaut, Chris Hadfield, even managed to broadcast a cover version of “Space Oddity” he performed on the International Space Station two years back, as his tribute to Bowie’s place in both contemporary pop culture and an interest in space.

On Bowie’s just-released, final album there was the track, “Lazarus”, a song reprising his current off-Broadway stage show by the same name, a work that itself evolved from his early film, The Man Who Fell to Earth. “Lazarus” had been originally scheduled to run until 17 January, but it might be a good bet that it will now be running rather longer. Beyond his film performances as Jack Cilliers, in Merry Christmas Mister Lawrence, or Tommy Newton, the space alien in The Man Who Fell to Earth, along the way, Bowie also portrayed Pontius Pilate, and a half dozen other highly idiosyncratic characters in other roles in of his cinematic career.

While to this author it was cinematic Bowie that excited, for so many others, even beyond his music, it was his public persona, his politeness, his intellect, his cultural nonce, his unerring sense of where fashion could go, and even his marriage to fashion icon, Iman, all of these located him both in the core and at the leading edge of much of late 20th century and early 21st century popular culture. He emerged from South London and by the time of his death had become a global musical citizen.

Now, in the aftermath of his death from cancer, there has been a huge global outpouring in return of feeling by people – famous and obscure – about the effect of Bowie’s work on their own lives. They have taken to print, electronic and broadcast media to testify how Bowie’s music had become an integral soundtrack for their own individual lives – and that his lyrics had been instrumental in buoying them through both the crises and quotidian moments of their own lives.

Meanwhile, David Bowie’s passing has come just a week-and-a-half after singer Natalie Cole’s death on 31 December 2015 from heart disease at the age of sixty-five. The daughter of the astonishing, barrier breaking singer, Nat King Cole – a black man with his own nationally broadcast television in the US back in the 1960s – in her early years, by virtue of her father’s work, Natalie Cole was surrounded by musical greats who were friends or artistic collaborators – or both – of her father.

After years of working increasingly through an array of musical genres such as funk rock, R and B, and soul, she slowly made a kind of U-turn towards the jazz and jazz-inflected ballads her father had been past master of singing. With that switch in styles, Natalie Cole scored a massive international hit in 1991, with a remake of one of her father’s signature tunes, “Unforgettable.” But that was a remake with a remarkable difference.

Digital recording techniques were now so advanced that her recording could be crafted as a duet with her late father’s own, earlier performance of this very same song – and it was released as both an audio recording and as an extraordinarily poignant video that flew to top of charts popularity globally and gave her (or, perhaps, both of them) a tonne of Grammy awards. Her own performance in this duet, both on its own merits and as an homage to her father, was intense and honest, breaking both the hearts of those who had loved Nat King Cole’s own music – as well as those being introduced to it for the first time. Natalie Cole had an active live performance career as well as roles in various films. And in live performance – especially the intimate settings of a nightclub like the Blue Note in Tokyo, where the author once heard her live, she was knockout performer.

Still, she had her own personal demons. She struggled for years with drug addiction and the results of that eventually led to illnesses that culminated in a kidney transplant later in life after years of dialysis and a public appeal for a kidney on television.

Asked about the influence of both Bowie and Cole on the newest generation of musicians, the author’s vocal artist daughter wrote that she had “long been a fan of Natalie Cole and the endless “teachings” I get through listening to her recordings. She had a very direct influence on what kind of jazz I ended up listening to as a young jazz music lover and I can feel her influence all over the way I perform. As for David Bowie, his influence on me has not been so direct, but it was more through the influence he has had on musicians that I listen to today. They both have such a direct and indirect influence on all of pop culture and its entertainers. They can be seen and felt in artists from jazz to punk rock.”

And then just six days after Cole passed away, on 5 January 2016, yet another enormously influential musician, French composer/conductor Pierre Boulez, passed away at the age of 90. As a composer, especially in his earlier years, Boulez had played a major role in the development of such edgy developments as integral serialism, controlled chance and electronic music. He was one of a trio of composers, along with John Cage and Karlheinz Stockhausen, who were numbered among the most important figures in 20th century “classical” music.

Boulez’ position as an extremely influential avant-garde composer came in tandem with his strongly put views on the evolution and role of music more generally in the contemporary world. Such judgments included the belief that “Any musician who has not experienced? — ?I do not say understood, but truly experienced ?—? the necessity of dodecaphonic music is USELESS. For his whole work is irrelevant to the needs of his epoch.” Or, “Why compose works that have to be re-created every time they are performed? Because definitive, once-and-for-all developments seem no longer appropriate to musical thought as it is today, or to the actual state that we have reached in the evolution of musical technique, which is increasingly concerned with the investigation of a relative world, a permanent ‘discovering’ rather like the state of ‘permanent revolution.’”

Surely not your grandfather’s music teacher!

And as a conductor with many of the world’s foremost orchestras, Boulez was especially renowned, loved (and occasionally hated) for his bravura performances of works by Béla Bartók, Alban Berg, Anton Bruckner, Claude Debussy, Gustav Mahler, Maurice Ravel, Arnold Schoenberg, Igor Stravinsky, Edgard Varèse, Richard Wagner and Anton Webern. Along the way, orchestras under his leadership garnered some twenty-six Grammy Awards during his career.

His acute sense of rhythmic precision, sans conductor’s baton, combined with his precise sense of tone led to musical legends about his actions as a conductor. The New York Times wrote of him, for example: “There are countless stories of him detecting, for example, faulty intonation from the third oboe in a complex orchestral texture.” During the height of his conducting career he maintained a crushing pace in which he was, concurrently, the musical adviser of the Cleveland Orchestra from 1970 to 1972, chief conductor of the BBC Symphony Orchestra from 1971 to 1975, and music director of the New York Philharmonic from 1971 to 1977, along with a number of other lesser posts.

Upon Boulez’ passing, The Guardian wrote, “‘Schoenberg is dead’; ‘Blow up the opera houses’; ‘Authenticity is a nightmare’; Henze? ‘rubbish’. Verdi? ‘dum de dum, nothing more’. Shostakovich? ‘the second or even third pressing of Mahler’: all the typically outspoken views of the great musical iconoclast of the late 20th century, composer, conductor, writer, theorist and thinker Pierre Boulez, who died last week after a long illness at the age of 90.

“This strident figure, who emerged from the postwar years as a turbulently individual pupil of Messiaen, was ready to rubbish most of history in the search for the one new path of the music of the future. He cast a huge shadow over the decades that followed, and as both creator and interpreter was surely the single most influential person in the musical life of our time. Forget Karajan; this was the man who moved our culture decisively forward and changed our taste for ever….

“And what of his own path-breaking music? That is another paradox: that this supposedly severe serialist gave us some of the most gorgeously voluptuous, colouristically French sounds of our time: dazzlingly virtuosic in Sur incises, innovatively electronic in Répons, sensually languorous in Le Visage nuptial, and massively complex yet inviting in Pli selon pli. Through his own radical music and his profound understanding of the music of others, he transformed our experience; we can only be deeply grateful for his influence, as our musical life looks for the next revolution.”

Taken together, Bowie, Cole and Boulez, collectively operating in their respective genres, via very different varieties of musicianship, and the growing impact of electronic engagement, greatly expanded the range of music available to their legions of fans and supporters. They, each, in their own unique ways, expanded the envelope of music – both in live performance and in treasured recordings. And along the way, they each changed, forever, the way we hear our collective global culture. DM

Photo: (Left) David Bowie performs during the first day of the Doctor Music Festival in a Pirineos little valley in Catalonia July 12, 1996. (Reuters) (Centre) Natalie Cole, shown performing September 3, 1999 at the “Soul Train Lady of Soul Awards” in Santa Monica (Reuters) (Right) Pierre Boulez in May 1996. (Reuters)

Become an Insider

Become an Insider