World

A short history of modern terrorism

The continuing roster of terror attacks goads J. BROOKS SPECTOR to try to put these things into a larger historical context. It does not make for an optimistic read, however.

In the past several years, we have become used to hearing and reading about an era (or for unlucky ones, living through such an event) where a kind of religiously infused terrorism carried out by nihilist, pathological thugs has thoroughly unhinged places around the globe. (For those protesting the use of the term “nihilist” in this context, we can argue that point. While the violence may speak to a goal, it seems brutally unconnected in any way to the point being made.) And so, for many, it seems we have entered a unique age where a new and terrifying form of militant action has come from nowhere to horrify us.

The point of this commentary, of course, will be that great transnational waves of activity are not unique to our own age, although the speed and extent of their impact have become new and particularly challenging issues, separate and apart from the death and destruction they have caused. We will return to those aspects in a minute, but first let’s take a quick look at some history.

During a seventy-year or so period, from roughly 1775 to 1848 (although British historian Eric Hobsbawm began his study, “The Age of Revolution” in 1789, thereby ignoring the American one), a revolutionary fervour took hold in many societies. These included most of Britain’s North American colonies, France’s Caribbean Sea colony of Haiti, France itself, the vast Latin American lands held by Spain from Mexico to Chile, Greece’s struggle to gain its independence from the Ottoman Empire, and then, finally, the wave of revolts that broke out in 1848 all across Europe – from France to Hungary. Originally inspired by the ideas of John Locke, Jacques Rousseau, Voltaire, and then on to Americans like Thomas Paine and Thomas Jefferson, the impetus eventually spread with the march of Napoleon’s armies as their campaigns thoroughly upended old political hierarchies and well-entrenched rulers – and drew upon and inspired the ideas of the Romantic Movement in the arts. Some of these revolts were, of course, more successful than others – those in 1848 were ultimately put down by loyal armies or by foreign intervention, even if the ideals were never quite fully stamped out.

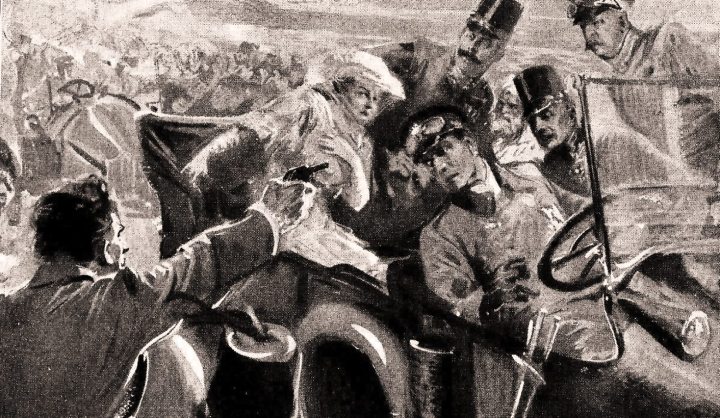

Forty years later, with the rising tides of ethnically exclusive nationalisms, and growing industrialisation and urbanisation across Europe (and to a considerable degree in America as well), a new wave of activism took hold in many nations. This time around, besides ethnic nationalist groupings and trade unions, some activists chose more violent means of direct action. For a generation and more, some radicals aimed their anger and frustration on the established political and economic order to provoke a fundamental reordering of the social, economic, and political structures of the affected nations. For some it became a wave of sometimes violent strikes and labour agitation, while for others it led to political assassinations of presidents, prime ministers, royals and – ultimately – the heir to the Austro-Hungarian throne, the act that set off the conflagration that became World War I.

Ten year ago, The Economist had written presciently, “Bombs, beards and backpacks: these are the distinguishing marks, at least in the popular imagination, of the terror-mongers who either incite or carry out the explosions that periodically rock the cities of the western world. A century or so ago it was not so different: bombs, beards and fizzing fuses. The worries generated by the two waves of terror, the responses to them and some of their other characteristics are also similar. The spasm of anarchist violence that was at its most convulsive in the 1880s and 1890s was felt, if indirectly, in every continent. It claimed hundreds of lives, including those of several heads of government, aroused widespread fear and prompted quantities of new laws and restrictions. But it passed. Jihadism is certainly not a lineal descendant of anarchism: far from it. Even so, the parallels between the anarchist bombings of the 19th century and the Islamist ones of today may be instructive.”

Then, over a half century later, in the 1960s, in many nations around the world – the US, Western Europe, and China, among other places – a vast upwelling of activism was fuelled by the “baby boom” generation as young people became big enough forces to assert real heft in the politics of their respective nations. This ranged from the anti-war protests in the US as well as the civil rights struggle in part; a broader, more violent social-economic critique in Western Europe by such groups as the Baader-Meinhof Gang, in addition to the vast waves of student strikes in that part of the world; and even the sometimes violent and thoroughly disruptive Red Guards of China’s Cultural Revolution. Here again, the assumption by many was that this was a unique moment in history.

And so we come to our own present era. Over the past two decades or so, there has been yet another wave of activism, this time ostensibly tied to Islam and encompassing lands stretching from Morocco to Southeast Asia. These now include al Qaeda and its various affiliates ranged across North Africa, Boko Haram in Nigeria and nearby nations, and ISIS/IS/ISIL/Daesh in Syria/Iraq, as well as groups in the southern Philippines, southern Thailand, Chechnya in Russia, Xinjiang in China, and various groups operating out of Pakistan, among other spots.

There is little evidence that there are organised, or that there are real, tangible connections between most of them. Instead, the connections seem more to be from a shared knowledge and encouragement of each other’s efforts, transmitted quickly by reporting by international media of these respective actions, as well as from their own efforts to make use of the Internet and social media. It is the ideas and inspirations that are shared. This seems largely true, even if some weaponry has been moved across some very porous borders – as with the spread of sophisticated arsenals from Libya southward, after Qaddafi was deposed.

Of course, it is also true that there is a sense of grievance – and often-shared grievances – on the part of many of the proponents of this latest wave. Even so, these grievances are wide-ranging and varied. Paradoxically, it is the very people who have had real economic and social opportunities in their lives that express these grievances so forcefully in their actions. However, it has been all too easy for some to claim it is all about the inherent violence of Islam; or that the tensions of the Israeli-Palestinian struggle are the central mechanism to what is goading such people onward; or that all of these actions are some kind of desperate struggle to resist domination by the rampaging West. (For the latter, such an explanation would be of little help in explaining the efforts by the Uighurs in western China or the Chechens in the Russian Caucasus lands or why privileged Saudi citizens move into this groove.)

Osama bin Laden was, for example, the scion of a rich construction firm-owning family in Saudi Arabia. And the perpetrators of the latest outrages in Paris now appear to have been French and Belgian citizens of North African descent, but who held a deep sense of grievance about the circumstances of their lives in the ban lieues of Paris and other French cities – joined together with the implicit temptation of a better outcome through a struggle against the predominant French society. And, of course, the nineteen young men who hijacked those four airplanes for 9/11’s deeds were also of Saudi Arabian origin and – mostly – studying in the US before they boarded those planes with their box cutters and their plan to behead the Government and the national economy.

For a more complete grasp of this global movement, we must also add other strains to this newest outbreak, not least the growing sense in the Maghreb and Middle Eastern nations that the odds have been systematically stacked against the working class and young people, thereby provoking the Arab Spring and eventually leading to the chaos of Syria (such societies are ones with a huge youth cohort). There are also the religious-ethnic tensions and political rivalries that have fuelled the fighting in the southern Philippines for decades, for example. Pile on top of all this the temptations that Daesh’s on-going struggle in Syria and Iraq can offer some kind of larger meaning in life and you achieve a toxic mix – even if some originally tempted to join Daesh later come to realise such fighting was not fundamentally about their imagined new religious order of things.

Again, as with The Economist, we puzzle over this. “What prompts the leap from idealistic thought to violent action is largely a matter for conjecture. Every religion and almost every philosophy has drawn adherents ready to shed blood, their own included, and in the face of tyranny, poverty and exploitation, a willingness to resort to force is not hard to understand. Both anarchism and jihadism, though, have incorporated bloodshed into their ideologies, or at least some of their zealots have. And both have been ready to justify the killing not just of soldiers, policemen and other agents of the state, but also of civilians.

“For anarchists, the crucial theory was that developed in Italy, where in 1876 Errico Malatesta put it thus: ‘The insurrectionary deed, destined to affirm socialist principles by acts, is the most efficacious means of propaganda.’ This theory of ‘propaganda by deed’ was cheerfully promoted by another great anarchist thinker, Peter Kropotkin, a Russian prince who became the toast of radical-chic circles in Europe and America. Whether the theory truly tipped non-violent muses into killers, or whether it merely gave a pretext to psychopaths, simpletons and romantics to commit murders, is unclear. The murders, however, are not in doubt. In deadly sequence, anarchists claimed the lives of President Sadi Carnot of France (1894), Antonio Cánovas del Castillo, the prime minister of Spain (1897), Empress Elizabeth of Austria (1898), King Umberto of Italy (1900), President William McKinley of the United States (1901) and José Canalejas y Méndez, another Spanish prime minister (1912).”

And this, of course, does not even count killings in the name of extreme nationalism such as the fatal shooting of Archduke Franz Ferdinand in 1914 by a Serbian nationalist.

The Economist went on to argue, “Mr bin Laden [or his successors or imitators, now] would surely delight in some dramatic assassinations today. Presidents and prime ministers, however, do not nowadays sit reading the newspaper on the terraces of hotels where out-of-work Italian printers wander round with revolvers in their pockets, as Cánovas did, or walk the streets of Madrid unprotected while looking into bookshop windows, as Canalejas did. So Mr bin Laden must content himself with the assertion that on September 11th, ‘God Almighty hit the United States at its most vulnerable spot. He destroyed its greatest buildings… It was filled with terror from its north to its south and from its east to its west.’ ” And so, instead of the individual terrorist attacking that solitary senior official or prince while they dawdle over coffee and cake, or a single bomber tossing an explosive projectile under an open touring car, the contemporary style of assaults in public spaces, using semi-automatic assault weapons, aimed at unwitting innocents has become the new “style du jour”.

The problem, now, of course, is that the impact of every attack is quickly magnified, many times over, from round-the-clock coverage on all electronic news channels around the world; by the constant chatter on Internet blogs by both proponents and opponents; by cell phone communications; by a whole array of social media channels; and, of course, by the growing use among such groups of encrypted communications technologies that are largely unbreakable by the authorities in any kind of immediate way. In fact, the authorities in many countries still remain largely baffled by this newest rise of activism and how to deliver a real hammer blow to it. Despite the propaganda of spy thriller action films, the authorities in virtually every nation affected simply do not have sufficient resources to track down every possible malefactor – let alone deal with them in advance to prevent any actions.

The comment attributed to the IRA in the wake of their bombing of the Brighton hotel in 1984 where the Conservative Party was having its meeting bears real importance. As the IRA gloated, “Mrs. Thatcher will now realise that Britain cannot occupy our country and torture our prisoners and shoot our people in their own streets and get away with it. Today we were unlucky, but remember we only have to be lucky once. You will have to be lucky always. Give Ireland peace and there will be no more war,” is both instructive and ominous as a foreboding of things that may yet come – especially when it is not in the hands of any one nation to deliver satisfactorily upon all the grievances held by a diverse swarm of different groups – and when the actors with the bombs and the guns are prepared to die for whatever cause they may espouse.

In the meantime, we may well have already entered a period where the real tension is over how many ways individuals’ civil rights and their rights to privacy will come under increasing pressure as authorities in western Europe and elsewhere (and perhaps the US as well) struggle to catch up to those who plan another Paris, another Radisson Blu Bamako, another Yola, Nigeria, or yet another bomb on an airliner, or in a bazaar, in a Third World shopping mall or in front of a mosque almost anywhere around the world.

Will European efforts to carry out more stringent checks of people entering the Schengen visa zone actually tamp down such actions, for example, if the perpetrators come from within that zone in the first place? And if western nations are stymied, can we reasonably expect that Indian authorities in Mumbai, the Nigerians or Lebanese do even better? And if not, what then?

In the meantime, if clever police work is insufficient, the air strikes will continue and, out of frustration, some day, soon enough, there will be growing popular pressure for some of those old-fashioned “boots on the ground” to deal a still stronger blow to those who would export their terror. DM

Illustration: Depiction of the assassination of Austrian Archduke Franz Ferdinand by Gavrilo Princip. Drawn by unknown.

For further reading, try these stories or the citations contained in them:

- Pentagon Expands Inquiry Into Intelligence on ISIS Surge in the New York Times;

- Inside the surreal world of the Islamic State’s propaganda machine in the Washington Post;

- Lessons from anarchy – Today’s jihadists, like yesterday’s anarchists, will fade. Terrorism won’t at the Economist;

- For jihadist, read anarchist at the Economist.

Become an Insider

Become an Insider