South Africa

Crime and punishment: Is lawlessness pushing South Africans beyond jurisprudence?

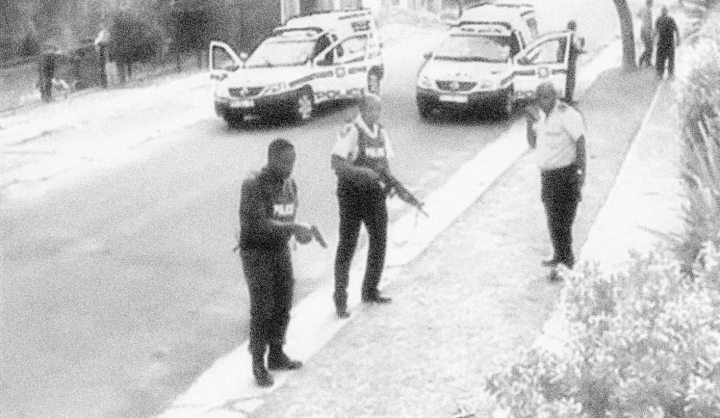

By late Sunday evening not a single person of the 703 who commented on a Facebook posting of video footage of police publicly executing a fleeing suspect in Krugersdorp, two weeks ago, expressed shock or horror at the lawlessness of the event. On Friday, an official attending a meeting to discuss the creation of safe spaces for women in Cape Town, described criminals as “crime carriers”. The combined circumstances of a lack of leadership, a general disregard for the law, a crisis in criminal justice and policing, as well as high levels of poverty and violent crime, have all placed South Africa on a dangerous precipice. Have we crossed a threshold? Was there ever a threshold to begin with? By MARIANNE THAMM.

When the police force in a constitutional democracy publicly executes a suspected criminal, without trying to apprehend him, it is acting way beyond and outside the law. The same applies to desperate citizens who band together to hunt down suspects, and setting them alight, or bludgeoning them to death. Almost a daily occurrence, this extrajudicial police conduct, and citizens’ response to crime in their communities, are often carried out in full view of young children. We have entered the realms of Judge Dredd and Dirty Harry.

When a government or state, including some of its own leaders, disregard the laws of the country, for whatever reasons, and resort to violence against their own people, and when citizens emulate the criminal conduct of their leaders, that country has reached a critical threshold.

We are now at that threshold.

The bulk of comments on radio stations and on media platforms, in response to the police extra-judicial execution of the fleeing criminal in Krugersdorp, has been overwhelmingly in support of the police action. These public responses should disturb us, and galvanise us into stop this dangerous slide towards accepting violence as, somehow, normal. It seems as if violence has become our way of communicating – our 12th official language.

Violence in post-democratic South Africa is no longer idiosyncratic. We seem to have slipped, seamlessly, from one form of state and public criminality, during apartheid, into a million different forms of lawlessness and violence. Violence has begun to define us, and appears to be the only means we have of restoring a sense of social order and control. It has become our only means of expression, and a deadly discussion between the state and its citizens, the citizens and politicians, and the citizens among ourselves.

“A little violence goes a long way when it takes on a meaning, when people begin to predict what will be punished. That meaning enables violence to function as a means of control. No social order could maintain itself solely by the physical effects of violence. Violence is always also a warning, a threat of the possibility of more violence. Violence itself is a language we all learn to interpret,” writes US sociologist Jay L Lemke adjunct professor of Communications at the University of California.

From the violent police response to student protests last month; the massacre of striking miners at Marikana; the shooting of protestor Andries Tatane; the killing of taxi driver Mido Macia, by police (and many other depressing examples), to the kind of violence spilling over at Masiphumelele in the Western Cape, and which flares up across the country almost daily, we now accept violence as a solution, and not a problem.

South Africa is a country where words conceal more than they reveal, a situation which the German philosopher, Hannah Arendt, suggested, rendered language unreliable. We have developed our own lexicon of avoidance, “challenges”, “housing opportunities”, “work opportunities”, “concomitant action” and “load shedding”. Just last week, a law enforcement official in the Western Cape described criminals as “crime carriers”, a perverse form of officialese which exposes a notion that crime is a disease, and that those who commit it are somehow “infected”, that they are vermin, vectors and pests like rats who need to be exterminated. Exploring the source of this violence or this criminality appears to no longer be an option. This might help explain the wild cheering at the cyber margins of the Krugersdorp execution.

Sometimes language actively embraces extra-legal violence. Former police commissioner Bheki Cele’s “shoot to kill” statement, and Lieutenant-General Zukiswa Mbombo’s suggestion before the Massacre at Marikana that “we need to act such that we kill this thing” are two examples the metaphorical hollow-point bullets aimed at the Constitution.

There are also displays of violence in the heart of government. Earlier this year, millions of television viewers watched plain-clothed bouncers violently remove democratically elected Members of Parliament from the National Assembly. The MP’s “crime” was their objections to the abuse of the public purse by President Zuma.

If there is, actually, a tiny glimmer of a “good story” to tell about contemporary South Africa, it is overshadowed entirely by this banquet of violence; criminal, private and state and the thick, uncouth tongues that nourish it. Who do we blame? Where do we begin?

We can start with a Minister of Police, Nkosinathi Nhleko, whose attention is elsewhere. Nhleko is distracted by attempts to undermine a report from the Public Protector which established that President Jacob Zuma unduly benefitted from multi-million rand upgrades to his private residence – at the expense of the citizens of South Africa. We can, also, move swiftly to the National Prosecuting Authority (NPA), which has been hobbled by a series of political appointments aimed at serving a political elite, rather than combatting crime. Then we can make a brief stopover at the intelligence community, where similar internal political feuds have provided the perfect enabling conditions for someone like international fugitive, Radovan Krejcir, to carve out a public high-profile life in South Africa for years, while bodies piled up around him. Add to all this, three disgraced national police commissioners, themselves preoccupied with propping up a political hierarchy, and hardly noticing the world around them spinning out of control. Below them are disturbing numbers of high-ranking police officers who have been drawn into these political intrigues, or who are, themselves, accused of criminal activities. As we speak, the suspended National Commissioner of Police, Riah Phiyega, is reportedly embroiled in a “dirty tricks” plan to “destroy her rivals”.

Little wonder, then, that communities who find themselves living in some of the most violent regions in the world no longer trust the law, the police, government or anyone else.

Those of us whose daily lives are touched by crime, and by this perverse theatre of violence, cheer and applaud the two policemen in Krugerdorp who executed the suspected criminal. And yet we are, in that moment, no better than the criminal we seek to see extinguished.

Elsewhere in the country, the day after the Krugersdorp story was published, the traumatised community of Masiphumelele in Cape Town, where there is NO police station, marched en masse to the Simonstown courts to demand the release of Lubabalo Vellem, a local community leader. We can remind ourselves that Vellem has been charged with murder, attempted murder, assault and grievous bodily harm, and inciting public violence. It is somewhat ironic, maybe not, that Vellem has long been at the forefront of attempts to get better policing for the community. Masiphumelele has been virtually at war for several weeks, following the murder of a popular young schoolboy Amani Pula, 14, who was raped and brutally murdered inside his home in September.

Lizette Lancaster, of the Institute for Security Studies (ISS), writing on how to tackle lawlessness in South Africa, cited the views of Italian economist Paola Mauro that in broad terms, lawlessness naturally flowed from systemic corruption. In this respect, South Africans, all of us, must, with a common purpose and solidarity, begin to search for a solution to the problems of crime, violence and general lawlessness in the country.

For Mauro, corruption and political instability – to which can be added, crime and violence – might be two sides of the same coin. While the members of the ruling party acknowledge these problems behind closed doors, there is a need to for political will to deal with these issues.

Lancaster writes: “At the heart of the problem lies the concept of civic morality. Civic morality, like the concept ‘ubuntu’, centres on trust and reciprocity of individuals and groups. In a 2006 article, ‘Investigating the Roots of Civic Morality’, the Polish academic, Natalia Letski, explained that the pursuit of civic morality required a collective sense of responsibility for the public good, where public gains are seen as far more important than individual gains. The pursuit of public good deters participation in corrupt activities or free riding, and enhances a general willingness to comply with rules and norms. Ultimately, public order and the rule of law become easier to implement, and resources can be redirected away from law enforcement as the means to deter negative behaviour towards socio-economic growth programmes.”

This civic morality depends, however, on more than just individual trust and compliance, but also on a government’s need to maintain a “status of legitimacy among citizens which will in turn increase the citizenry’s willingness to comply with the rules made by the state.”

“It follows that if any public agency or its officials do not meet the standards required by the citizenry, the public is likely to start breaking the law and find excuses for dishonesty,” writes Lancaster.

When residents of municipalities watch infrastructure crumbling, their services limited or non-existent, while government officials drive expensive cars, squander public money on luxurious personal items, attend awards ceremonies or other glamorous events, Cabinet Ministers post selfies on social media, we may remember Groucho Marx’s observation: “Who you gonna believe, me or your eyes”. In South Africa many people will, more likely, believe their empty stomach.

In the same week that students across South Africa took the #FeesMustFall protest to the seat of Government, news broke that R19 billion had been wasted in the North West Province by 36, 000 “ghost employees”, who have been drawing a salary in the region. It is a staggering mount which would, to the ordinary citizen, more than adequately cover the anticipated R2.2 billion shortfall as a result of the “no-fee increase’ in university fees next year.

The distinct lack of ethical leadership and corruption in all spheres of South African life including the SABC, South African Airways, Eskom, the Post Office, and most importantly the South African Police Services, create a pathological combination of circumstances that place the country on a precipice. These circumstances are garnished with a lethal cocktail of slow economic growth, high unemployment and extreme poverty.

Then there are the continual huge financial bailouts of state enterprises, which are run on behalf of a political elite, rather than for those they are meant to serve. From their side, private sector corruption and lawlessness helps nudge the country to the edge. The Lewis Stores and Monarch Insurance “mis-selling” of credit insurance are just a few of the bad examples. Is there any hope for us, the citizens of this country?

Well yes, sort of. The first move would be to create a visible shift in the political landscape, in the upcoming 2016 municipal elections. The ruling party intends, it claims, to clean its ranks by proposing that those who stand for election must be vetted, and be credible leaders of communities. This may be too little far too late.

The massive march by Julius Malema’s Economic Freedom Fighters in Johannesburg, at the end of last month, sent a powerful signal to those in charge. The message was clear: Support for the African National Congress is no longer guaranteed, and cannot be taken for granted. Students have also demonstrated to leaders, especially those who have relied on their “struggle credentials” for support, that this no longer holds sway. Delivery and service to the people is what will count at the end. For ordinary citizens, change will have to come through the ballot, and an active and fearless civil society.

In a paper, produced in 2005, Lancaster of the ISS, cited an unpublished NPA survey of the level of compliance with the country’s laws, and confidence in the criminal justice system. Back then, before the Zuma’s presidency, research indicated that “most South Africans are not lawless or corrupt, and they respect state institutions. Close on 90 percent of the respondents frowned upon general suggestions of bribery, cheating, breaking of traffic or other laws and the misuse of state resources. They displayed a high level of trust in state institutions such as Parliament (84 percent), the government (85 percent), the public service (82 percent), South African Police Service (SAPS) (79 percent), prosecution services (78 percent) and the courts (82 percent). However, they had far less trust in the officials who worked in these institutions. Only 37 percent trusted politicians, 50 percent police officers, 48 percent prosecutors and 54 percent magistrates.”

Six years later, in 2011, the South African Reconciliation Barometer, published by the Institute for Justice and Reconciliation, found that 65 percent of South Africans “have confidence in national government.” Another study, also in 2011, by the Human Sciences Research Council (HSRC) found that 74 percent of all South Africans believed that corruption has increased in the past three years. Two-thirds of the respondents (66 percent) felt that bribery and abuse of power for personal gain were prevalent among members of the SAPS. A substantial minority of people perceived widespread corruption among Home Affairs officials (38 percent), national politicians (37 percent), officials awarding public tenders (37 percent) and people working in the judicial services (36 percent).

Some of the reasons why South Africans believed corruption has thrived is due to a lack of transparency in public spending (30 percent), close links between business and politics (29 percent), and the acceptance of society that corruption is part of daily life (28 percent). A tiny shard of light in this all is that, according to this study, 82 percent of South Africans believed that citizens could make a difference in the fight against corruption.

Then there is our new shimmering lodestar – the one that has replaced the Freedom Charter, in a measure – the National Development Plan (NDP), which suggests that in 2030 a collective onslaught on corruption will result in “a corruption free society, a high adherence to ethics throughout society and a government that is accountable to its people”.

President Zuma, and those who surround and prop him up politically, (those who do so economically, will simply shift attention to where they can influence) will no longer feature on the political landscape at that point. But how much of the landscape will be left as it is now and how much would we have been altered because of it?

Democratic freedoms will, and must be defended in a democratic fashion, even when the state or its agents act undemocratically. Through a free media, an active and brave civil society – which South Africa possesses – through legal political opposition, through the courts and the rule of law and by not ourselves becoming that which we most despise. DM

Photo: A frame grab from the Krugersdorp police’s shooting of a suspect.

Become an Insider

Become an Insider