World

WWII and Vietnam War, the conflicts that defined the modern world

The end of World War II in Europe 70 years ago and the end of the Vietnam War 40 years ago bracket an astonishing period of global history. As we mark these important anniversaries, what can we learn from these terrible conflicts? By J BROOKS SPECTOR.

Henry Luce, one of the founders of both TIME and Life magazines and a major powerbroker in Republican Party circles for many decades, had famously declared in 1941 – even before the United States had entered World War II – that the twentieth century was going to be known as “The American Century” and that it was necessary for America to eschew its traditional isolationism and to embrace the global challenge presented by the ascendency of fascism. Luce held nothing back in his flamboyant statement, when he had written, “Throughout the 17th century and the 18th century and the 19th century, this continent teemed with manifold projects and magnificent purposes. Above them all and weaving them all together into the most exciting flag of all the world and of all history was the triumphal purpose of freedom.”

For years afterwards, in the wake of the destruction of World War II and the great changes of international circumstances thereafter, and until the disaster of America’s participation in the Vietnam War, it had seemed as if Luce had been closing in on something very big – that his self-declared American Century was poised to transform global geopolitics. From the vantage point of 2015, and looking backwards over this 70-year period, this past week includes two anniversaries that could well be used to mark that special period in that American Century that defined the limits of the US’s near-total supremacy in world affairs.

The final surrender of Germany came on 8 May by Admiral Karl Doenitz (the formal surrender to the western allies took place on the 8th but because it was already the 9th in Moscow, the West and Russia commemorate the German surrender on different days). By that date, the American military machine had already reached the German town of Torgau on the banks of the Elbe River two weeks earlier where those forces linked up with the Soviet army. By 8 May, the allies had been victorious over Nazi Germany virtually everywhere, save for pockets of remaining resistance in far northern Germany and the Alpine regions of Austria, northern Italy and far southern Germany.

There was, of course, that-not-so-small matter of the other major partner in the victorious coalition, the then-Soviet Union. After horrific early losses when Germany invaded Russia in 1941, the USSR’s armies had finally regained their footing and they had marched west from the very gates of Moscow, St Petersburg and Stalingrad, sweeping right past Berlin, in order to meet up with those Americans driving from the West. Inevitably there were the photogenic moments with the shouts of “comrade” and “tovarish” as the two armies met and soldiers embraced in those astonishing, heady days.

In truth, however, in the Pacific, there was still months of warfare left, even if it seemed to most people that it was only a matter of time before the Japanese finally surrendered to the overwhelming force of the US and Britain. In fact, the Japanese surrender only occurred once the Americans had used their new atomic weapon on the cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, convincing the Japanese leadership that there was absolutely no point in continuing the struggle. Ironically, the Germans had surrendered before the new nuclear weapons were ready for use, even though their development had begun when leading physicists (some only newly arrived in America after fleeing the Nazis) had urged the Roosevelt administration to start solving the puzzle of creating atomic weapons, for fear the Germans would do so first, with truly baleful consequences for western civilization.

By the time of the German surrender, new US president Harry Truman (who had suddenly been catapulted into his office after President Franklin Roosevelt passed away from a stroke after some 12 years in office), had met with Soviet premier Joseph Stalin and British prime minister Winston Churchill at Yalta in the Crimea in order to redraw the map of Europe. The decisions, of course, largely confirmed the actual disposition of military forces rather than more utopian goals. A second summit, this time in Potsdam in occupied Germany, confirmed the division of Germany and Austria into zones of occupation (US, British, French and Soviet) and set out an ultimately unfulfilled promise of elected governments across Eastern Europe.

By war’s end, Europe and the UK were thoroughly exhausted by six year’s of war or from the German occupation. Even the USSR was faced with the task of rehabilitating hundreds of thousands of square kilometers of territory that had been a vast battlefield from the Arctic Circle to the Black Sea. And the UK had been financially devastated by cost of fighting the war since September 1939 as well as having faced years of bombing attacks by German aircraft and then their newly developed V-1 and V-2 missiles.

In effect, in 1945, the US stood virtually alone in the world as the nation that had become economically stronger by serving as the “arsenal of democracy” (the phrase first used by Roosevelt in a radio address on 29 Dec 1940, nearly a year before the US had entered the war officially). The US government had mobilised the full productive industrial power of the country and brought that to bear in support of its own 12 million men and women under arms on four continents, in addition to supplying its allies around the world with the materiel for modern warfare. Unique among the major combatants, save for the initial Japanese attack on Pearl Harbour in Hawaii and the occupation of two isolated spots in the Aleutian Islands chain off Alaska, virtually no part of the US had been directly touched by the war’s fighting.

With the usual economic and industrial powerhouses of Europe and Asia nearly prostrate from the war, the US economy represented for over half of the global GDP – an unparalleled circumstance for one national economy. Americans could be forgiven, perhaps, for thinking that their global military and economic pre-eminence and the new global institutions that they had helped create, the UN as well as the international financial bodies that emerged out of the Bretton Woods agreements and the Dumbarton Oaks meetings, were poised for a reshaping of the global geopolitical order in a way that had not occurred since the Peace of Westphalia in 1648 firmly established the idea of national sovereignty.

But the rivalry with the Soviet Union that evolved directly from the peace arrangements after World War II; the imposition of Soviet-style institutions on a wide swathe of Eastern Europe, “from Stettin in the Baltic to Trieste in the Adriatic” as Winston Churchill would memorably describe in his ‘Iron Curtain’ speech in 1946; plus the collapse of the Nationalist government in China to Mao Zedong’s communist party and army just three years later, all began to breed a fear among increasing numbers of Americans (and not a few opportunist politicians like Wisconsin senator Joseph McCarthy) that despite America’s recent overwhelming victory in World War II, a new even more dangerous menace lay just over the horizon. Once it became clear the Soviet Union had obtained those hard-won atomic bomb secrets by the efforts of its own scientists but also because of information purloined from the western nation’s Manhattan Project, it seemed increasingly clear to many that the US was about to confront yet another, new existential crisis.

Such fears about this new threat finally pushed many heretofore isolationist Republican politicians to back unparalleled efforts for an American government such as the Marshall Plan for rebuilding Europe, as well as the gradual stitching together of a series of alliances that girdled the globe, beginning with the establishment of the Nato alliance. American diplomat George Kennan’s extraordinarily influential ‘Long Telegram’ sent from his post at the US Embassy in Moscow shortly after the war analysed the deep sources of Russian foreign policy behaviour and Kennan had coined the concept of “containment” for dealing with the Soviet Union – an approach that quickly became incorporated into the broader American strategic doctrine. This quickly merged with the US decision to defend the then-flailing states of Turkey and Greece from Soviet pressures – as well as growing concerns over the possibility of communist party victories in both French and Italian elections.

Soon enough, American policymakers began to see containment as a global mission statement, and the need to create an alliance structure that replicated the early success of Nato, but then reached around the globe, across the Middle East with Cento, to Southeast Asia via Seato, and then on to the Anzus Pact with Australia and New Zealand. The 1950 invasion of South Korea by the North Korean government (Russia and the US had taken the Japanese surrender on that peninsula and were supposed to lead the country to independence in a union of the two respective parts) was finally repelled by the combined efforts of numerous UN members under US leadership. But this conflict helped cement the idea that the West – and the US in particular – was facing a sustained, unrelenting threat from a Sino-Soviet block of communist-led nations.

This Manichean-style understanding of geopolitics by Americans, underpinned by the American proclivity to see international relations as fundamental contests of good and evil (drawing upon the muscular religious philosophy of Reinhold Niebuhr that had earlier been applied to the deadly struggle against fascism), became wedded to a deep sense among Americans that theirs was an exceptional nation with a mission “to make the world safe for democracy”. All of these ideas made it increasingly easy for American policy makers, along with other influentials, to couch their support for South Vietnam – once the French had given up trying to hold onto Indochina after their deeply traumatic defeat at Dien Bien Phu on 7 May 1954 – as simply the newest episode of that near-universal struggle against a global evil.

The initial American participation in the war over the fate of South Vietnam began with the assignment of a small number of military advisors and trainers sent to South Vietnam. But as that war continued to go from bad to worse for the South Vietnamese, President John Kennedy, then presidents Lyndon Johnson and Richard Nixon continued the military build-up to around half a million US personnel on the ground – and then expanded the war into neighbouring Cambodia as well in 1970.

This Vietnam effort, relying as it ultimately did on a conscript army of increasingly reluctant draftee soldiers and facing vociferous opposition by the country’s university students (themselves now increasingly subject to the conscription that supplied the military) eventually broke the will of continuing the US effort in Vietnam. By 1973, virtually all US ground troops had been withdrawn from the theatre of war, but that continuing support for the flailing regime based in Saigon tied America to the ultimate failure and collapse in South Vietnam.

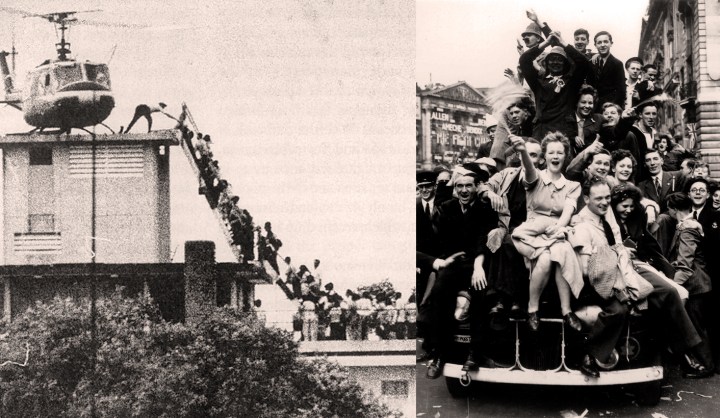

By the time vanguard North Vietnamese army units had rolled into Saigon, US Marines protecting the American Embassy were left with trying to cope with a giant crowd of terrorised South Vietnamese (many who had earlier thrown in their lot with the Americans), and all desperate to escape their expected fates under the new regime. Once the end came on 30 April 1975, US military helicopters had been reduced to ferrying small groups of Vietnamese from the final landing pad on the roof of the embassy and then on to US Navy vessels in the South China Sea.

There is no way to describe the ultimate futility of this military intervention as anything other than a disaster for America – and, of course, much more directly for the many hundreds of thousands of civilian Vietnamese who died in the ensuing crossfire, or as combatants themselves. After the debacle, American diplomats spent considerable time and energy attempting to reassure American allies in the region that the US was not engaged in a long-term pullout from the region, despite the North Vietnamese flag now flying over the presidential palace in Saigon – now newly rechristened as Ho Chi Minh City.

But to many, the self-evident American defeat in Southeast Asia seemed an inevitable harbinger of a longer term American decline – and one that could only continue on into the future. The dramatic twists to that view came sooner than anyone could have expected however. The end of World War II had brought a decisive end to centuries of conflict between Germany and France, as the two long-time antagonists were crucial in forging the European Economic Community and then the EU and as the US and Germany similarly forged a firm partnership. Soon enough after World War II, nearly all of the European powers quickly lost their will or strength to maintain those colonial empires around the world. This led to the unraveling of those empires and the birth of a plethora of new, independent nations across Africa, the Middle East and Asia. The decisive defeat of Japan also created space for a resurgent China (although that saga took much longer to play out – and was aided, curiously, by the visit of US president Richard Nixon to China – right in the midst of America’s involvement in the Vietnam War).

However, the greatest irony that followed the seemingly inevitable decay of the United States, post-Vietnam, came just 15 years later when the Soviet Union imploded, all of its constituent republics declared themselves to be independent, and the USSR’s European satellites in the Warsaw Pact found new homes in Nato and the EU. The relative recovery of the US economy – even in spite of that near-miss of the 2008-9 financial crisis – and the continuing inertia and lack of growth in most of Europe and the overall weakness of the Russian economy now means that the future increasingly looks like a contest, or at the minimum a tightening rivalry, between a economically blooming and military resurgent China and a still resourceful America. And so the key question of how that will look, 70 years from now, must be anybody’s guess. DM

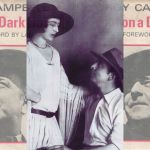

Main photo: (Left) A member of the CIA helps evacuees up a ladder onto an Air America helicopter on the roof of 22 Gia Long Street April 29, 1975, shortly before Saigon fell to advancing North Vietnamese troops. (Right) A handout image provided by the Imperial War Musem in Britain of crowds celebrating VE Day on the bonnet and roof of a car in United Kingdon as they celebrate VE Day in 1945 in war damaged London. Sunday, EPA/IMPERIAL WAR MUSEUM

Become an Insider

Become an Insider