South Africa

Post-Statue SA: What will be left when the toppling is done?

Now that Rhodes is gone, RICHARD POPLAK takes a trip to Pretoria, and asks whether the Voortrekker Monument will be the next to fall.

I was troubled by a recurring dream: One morning I see a crowd coming my way, laughing and singing, carrying ropes and crowbars and hammers. I realise that they have come to topple me, to drag my body down into the street. I am afraid that I will fall to pieces if I move. I do. I expect that they will leave me to rot, as a warning to all those whose hearts were hardened. But no, they scavenge me for souvenirs. My eye becomes a paperweight, my foot a doorstop. What bits of me will make bookends, flowerpots, stepping-stones, a wreck for the bottom of a fish-tank? But those who pull me down are surprised to see a sticky heart pacing out the confines of my ribcage.

—Ivan Vladislavic, “We Came to the Monument”

I.

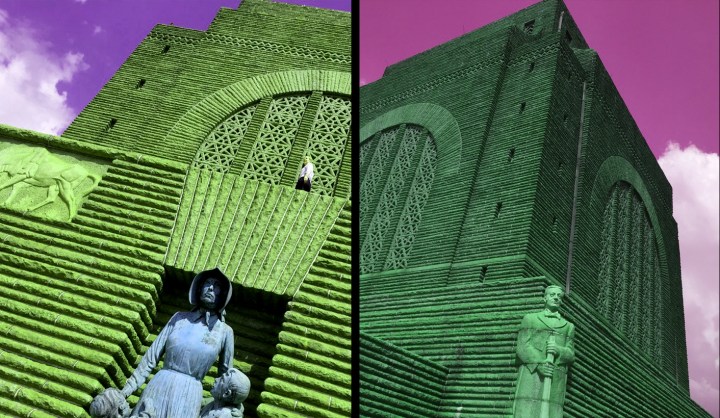

A road trip through Post-Statue South Africa: up the N1 from Johannesburg to the N14, exit on the M7, track the heebie-jeebie vibes to a boomed entrance at the bottom of a hill. Pay R60 per adult (!), park, and enter through the gift shop. Before you—above you—hulks the most indomitable structure ever built by the hands of man. On the Friday following the dismantling of the Rhodes sculpture at the University of Cape Town, one of the more contentious cultural moments in the history of this young country, I wanted to know what, if anything, was happening at the self-proclaimed “biggest Monument in Africa.”

Nothing was happening.

Or, rather, what has always happened was happening: kids powered through 1,000-calorie lunches; families walked slowly up the impossible steps; tourists took snapshots; toddlers rode horses in the Western-movie paddock. The moment the visitor crossed the boomed entrance, an alternate South Africa fizzled into view. The Voortrekker Monument exists outside of time, in a pocket of vacuum-sealed history floating in a sea of pretend context.

In the gift shop, after perusing the “oranje, blanje, blou” flag-branded booze glasses, I took a fistful of literature and struck for heaven. “Visitors walk through a black wrought iron gate with an assegai motif,” I learned from a pamphlet. “This symbolises the might of the Zulu King Dingane, who barred the way into the interior.” Thereafter, the cowed visitor entered a ring of “64 wagons, cast in terrazzo,” that “symbolically protect the monument” while commemorating the Battle of Blood River (16 December 1838). The laager, I read, “[also] symbolically protects the Afrikaner and his culture against foreign onslaught.”

Having ascended the stairs to the foot of the monument, I then came face to ankle with an enormous, weather-scarred entity called “Women and Children Statue.” Standing 4.1 metres high and weighing over 2.5 tons, it depicts a Voortrekker matriarch staring into the distance, ignoring the minor travails of this life and focusing on the raptures of the next. At her skirts are her children, a boy gazing up at her in terror and awe, a girl burying her face in fistfuls of bronze cloth. This too is a symbol—of womanly sacrifice, of matronly forthrightness. On both sides of the statue the sculptor had chiseled buffalos, “symbolising the dangers of Africa.”

Next up, the coup de grace: Cenotaph Hall and the empty sarcophagus illuminated precisely at noon every 16 December by a Godly beam of sunlight that pours through an opening in the cupola, embossing the words Ons vir jou Suid-Afrika with a momentary blast of heavenly gold.

What, I wondered, does this surfeit of meaning actually mean?

When the Monument was inaugurated on 16 December 1949 in front of 250,000 members of the volk, it was a clear statement of Afrikaner exceptionalism and belonging, a theme park of coded signifiers that only insiders could interpret. You were either able to read the Voortrekker Monument’s stone hieroglyphs, or you were terrified by their inscrutability. If Justinian saw the design of Constantinople’s domed Hagia Sofia in a dream, architect Gerard Moerdijk must have encountered the plans for the Monument in a nightmare. It is simultaneously millenarian and apocalyptic, a subversion of Art Deco’s Machine Age imagery in service of a pornographically detailed past.

Only a day after a statue of Rhodes was dismantled in the university he bequeathed to the country he stole, the Monument stood as a symbol representing a country comprised of symbols, all clanging around like neutrons and protons in the nanoseconds before an atomic explosion.

So the visitor asked, as he stared at History Inc.: Must the Monument fall, too?

II.

The statues were always going to be a problem.

At the turn of the regime the country was littered with the bronzed likenesses of Paul Kruger, Barry Herzog, Louis Botha, Jan Smuts, Hendrik Verwoerd and, of course, Cecil John Rhodes, to name but a few. None of these men were committed to an inclusive, multi-racial South Africa, and after the fall of Apartheid it would have surprised no one had they fallen too.

Across the globe, in other recently refreshed regimes, statues were being toppled, smashed, melted, blown to smithereens. The famous granite representation of Lenin’s head that stood on the gloomy side of the Berlin wall was chopped into pieces and buried in an unmarked grave beneath a parking lot. The cleansing goes on ‘til this day: since Ukraine’s pro-Russian president Viktor Yanukovych fled the country last February, 158 Lenins have met the bulldozer. In Schwerin, a town in what used to be East Germany, the last Lenin in Western Europe still stands, unflinching in the face of a battle to take him down. “In this modern world, we are told Lenin plays no role,” a local historian named Ralf Wendt told McClatchy. “But we cannot totally ignore our history. The monument is a document. It says who he was, and that says something about who we were, and are. I don’t understand the need to tear it down or cover it.”

In 1990 South Africa was pocked with over 3,600 statues representing the major figures of colonialism and the Apartheid years, and hundreds of memorials commemorating everything from the Boer War, the glory of die Taal, and, of course, the Great Trek. Hundreds have been dismantled. Most have not. Toppling statues did not fall within the Rainbow Narrative, and nor did it appeal to democracy’s early leaders, who were more focused on reconciliation than on remodeling.

This decision made for some strange social occasions. During Thabo Mbeki’s 1999 presidential inauguration, celebrated at Cape Town’s Union Buildings, the gala ceremony was attended by two enormous pariahs: giant statues of former presidents Louis Botha and Barry Herzog. A decision was taken to fence off the statues, to try and forget them without reducing them to dust.

Opposition parties claimed this was an ANC attempt to shroud the past. But the real question was where the shrouding would end if it began. After all, the Union Buildings were built by a certain Sir Herbert Baker, one of those Albert Speer-ish architect types who absolutely adored power. He built monuments across the British Empire to the British Empire and wrote of a structure in Delhi: “It must not be Indian, nor English, nor Roman but it must be imperial. Hurrah for despotism.”

What were Mbeki and his fellow celebrants to fence off, and what were they to leave unfenced? Every inch of public space in South Africa was programmed with either colonialism or Apartheid’s language. The entire built environment, from our institutional buildings, to our roadways, to the placement of our neighbourhoods—all of it spoke to a past that some people were compelled to remember, others wanted valorised, and still others were determined to forget. How were we supposed to live in all this clutter? How were we to divest buildings and statues and monuments and entire cities of their awful power?

And what were we supposed to do with the statues that hadn’t been built?

III.

Every now and then, South Africa has been subject to one of those Mbeki-gala statue controversies, small pokers of rage aimed at some bronzed pigeon toilet or other. But let’s give it to Chumani Maxwele, the 30-year-old student who forever changed the debate in this country with nothing more than a pile of shit. On 9 March 2015, Maxwele led a small protest at the bottom of UCT’s “Jammie” Steps, middle of Madiba Circle, during which a dozen students doused a statue of Cecil John Rhodes with human excrement. Suddenly South Africa’s bastion of white, intellectual propriety was flailing in post-transition slime.

“As black students we are disgusted by the fact that this statue still stands here today as it is a symbol of white supremacy,” spat Maxwele. “How we can be living in a time of transformation when this statue still stands and our hall is named after [Leander Starr] Jameson, who was a brutal lieutenant under Rhodes?”

And so the fun began.

Did these students not ken their history, concerned onlookers wanted to know? Were they unaware that Rhodes had kindly gifted this land to the olde Cape Province so the so that an institution of higher learning could be established on its stately slopes? Did the naming of the circle in which the statue stood after Madiba not cancel out Uncle Cecil’s historical freight, and render his likeness magically benign? Were there not more important things to worry about—like corruption and Nkandla and sundowners over Camps Bay?

Rhodes is History, and History is important. Leave the man be.

To hell with that white supremacist bastard, ran the counter-argument. And to hell with the agonisingly slow pace of transformation at the university built around his legacy. A movement called UCT Rhodes Must Fall, convened by the student representative council, was quickly established, and issued a mission statement that went much further than mere shit-slinging. “This movement is not just about the removal of a statue,” it read:

The statue has great symbolic power—it is a glorifying monument to a man who was undeniably a racist, imperialist, colonialist, and misogynist. It stands at the centre of what supposedly is the ‘greatest university in Africa’. This presence, which represents South Africa’s history of dispossession and exploitation of black people, is an act of violence against black students, workers and staff. The statue is therefore the perfect embodiment of black alienation and disempowerment at the hands of UCT’s institutional culture, and was the natural starting point of this movement. The removal of the statue will not be the end of this movement, but rather the beginning of the decolonisation of the university.

And by extension the country. UCT Rhodes Must Fall birthed similar movements, all of which were powered by a re-upped Black Consciousness that applied Biko’s astringent dictums for the Facebook age. This wasn’t an inclusive movement; it rejected the language of Rainbowism for something much, much harsher. Rhodes Must Fall wanted white professors replaced with black professors, white names replaced with black names, and an African university to stand where a European one once did.

Where better for all of this to happen but in another of South African history’s collapsed dwarf stars, the chunk of Cape Town that embraces UCT in a Rhodesian bear hug. In this zone of non-space, a diorama of colonial whiteness all but untouched by the death of Apartheid, Rhodes Must Not Fall or the entire superstructure was threatened.

Rhodes is the door behind which the real Iron Throne glimpsed.

What made Maxwele’s assault against him so dangerous was precisely the fact that it was not an attack on history.

It was an assault on the present.

IV.

Last Thursday, Rhodes fell.

In the lead-up, there was much debate, as befitted an institution governed by Democratic Ideals. Following an emergency meeting of the UCT council last Wednesday, which was finally stormed by enraged students after it ran overtime, Vice Chancellor Max Price announced the inevitable.

The statue would go.

What happens to the plinths on which old statues used to stand? In his short story “Propaganda by Monuments”, written shortly after both Apartheid and the Soviet Union uttered their death rattles, the author Ivan Vladislavic tells the tale of a New South African entrepreneur named Khumalo who, hoping to open a commie-themed tavern, aims to purchase a decapitated Lenin bust from a Russian named Grekov. Muses Grekov after the statue has been felled: “[I]t was hard to imagine something else in its place. But that’s the one certainty we have…that there will be something in its place.” Or, as the academic Christopher Warnes put it, “History—the actual events of the past—exists outside of the narrative mediations perpetrated on it, and history cannot be changed by eradicating its traces and artifacts.”

I prefer to look at it another way: When historical narratives are scrambled by grand theatrical gestures, the resulting vacuums are almost always filled by versions of the same.

This doesn’t mean that Rhodes Must Fall is a doomed venture. Not by any means. The movement was—is—essential largely because it took on an institution that existed outside of time, an intellectual la-la-land that for one brief, bracing moment was yanked to earth and forced to disgorge its own tail. But it does have precedents, other movements that have made similar gestures that have been co-opted by forces far greater than the movements themselves. In fact, as Ranjeni Munusamy wrote in these pages, Rhodes Must Fall can be traced back to statements that Economic Freedom Fighters Commander in Chief Julius Malema made in his inaugural Parliamentary address.

Referring to that contested statue of Louis Botha—subsequently defaced!—he said, “It is people like this who made white South Africans think they are superior and if we continue celebrating them, we are equally perpetuating white supremacy. The statue of Botha outside this Parliament must go down, because it represents nothing of what a democratic South Africa stands for,” Malema said.

The EFF has made much political hay out of recent events, while the ANC has spoken out repeatedly in defence of the bronze men on horses. Zuma, speaking on April 10 at the opening of the Chris Hani Memorial and Wall of Remembrance at the Thomas Nkobi Memorial Cemetery in Boksburg, said, “We are aware of the frustration of our people when it comes to colonial and racist figures. It is true that transformation with architecture is not happening fast enough, but destroying the figures is not the solution. We need to observe the law in this regard.”

“Transformation with Architecture”—Herbert Baker couldn’t have put it better. My guess is that the ANC is betting that the issue will burn itself out like most student whims. Removing statues is a disruption. The ruling party, as we’ve all learned, likes things just the way they are.

But the EFF will not let this go. It’s opposition politics at its rawest—nothing makes good TV like a toppled statue. And while they can lay some small claim to sparking this movement, South Africa’s statues were lying in wait for this moment, preparing to leap off their plinths and into the maelstrom of the present, covered in buckets of human shit.

Maxwele’s punk agitprop has not so much been co-opted—and nor has it been hi-jacked, as now-suspended SABC presenter Eben Jansen insisted during his famous live-to-air meltdown courtesy of EFF spokesperson Mbuyiseni Ndlozi. Statues have become mainstream politics. Colonial and Apartheid-era figures join Nkandla as pawns on a political chessboard. The DA will remain silent. The ANC will insist on rule of law. And the EFF will use every contested statue to push the ruling party further off the board, until it’s all such a mess that someone from deep within Herbert Baker’s Union Buildings shrieks “checkmate!”

V.

What of the Voortrekker Monument, the biggest, baddest manifested memory of them all?

In his story “We Came to the Monument”, Vladislavic imagined that it would become the refuge of a small band of Afrikaners during an apocalyptic meltdown. They huddled under the cupola while the city burned, stealing bonnets off the dummies in the museum displays.

“The Monument endured,” wrote Vladislavic.

Or perhaps Sunette Bridges and Steve Hofmyer will chain themselves to the Cenotaph and stay there until album tours lure them away. When Constantinople finally fell to the Turks and became the centre of the Ottoman Empire, Justinian’s Hagia Sofia became a palimpsest upon which the new rulers inscribed first their religion, and then their secularism. Perhaps the Monument will be repurposed, made into a historical funhouse that encompasses all the streaks of the South African rainbow. Maybe it will be stripped of its meaning and rented out as a storehouse for dead statues from dead regimes across the world—history’s clearing house.

Maybe it will become a car park. A helipad. A rocket launcher.

One thing is certain: Rhodes Must Fall represents a turning point—a moment when South African society is abruptly introduced to its shortcomings, and is remapped in a fundamental and lasting way. The new cartographers will not be gentle, but the time to clear the clutter has come.

Out with the old, in with the new, and all that. Let’s just hope that the Monument—where manufactured nostalgia meets genuine, rock-hewn millenarianism—is just a version of the past, and not a vision of an endless South African future. DM

Photos of the Voortrekker Monument by Richard Poplak.

Become an Insider

Become an Insider