Maverick Life

The Rumble in the Jungle: Forty years later, still the greatest fight of them all

One of the most famous events in sports history, the “Rumble in the Jungle” – the heavyweight boxing title fight between George Foreman and Muhammad Ali in Kinshasa – took place forty years ago. J. BROOKS SPECTOR considers its continuing impact.

The writer once worked for an ambassador who was a fervent boxing fanatic. Asked about this, she explained that she had grown up in the Bronx (in New York City) and enjoyed watching boxing training in neighbourhood gyms as well as collegiate boxing tournaments – and she loved those televised matches from what was later called the “golden age of boxing”.

The thing of it was, she had also figured out that some of the senior government types in the foreign government she dealt with in her job were also boxing enthusiasts – and one of them even operated a gym and managed a string of rising local fighters. As a result, the only thing to do was order a special shipment of the best boxing films available on video so that ambassador could show them at her home to her government interlocutors – Somebody Up There Likes Me, The Harder They Fall, Rocky and The Champ, among others. One just never knows.

Of course, the first Sylvester Stallone epic, the surprise 1977 film hit, Rocky, had quite unexpectedly made boxing popular with people who rarely, if ever, had a kind word for the sweet science. Instead, these people were the kind of folks repulsed by boxing’s brutality and violence, its increasingly obvious underworld connections, and a common understanding that boxing made its crooked promoters rich, left crippled former fighters brain damaged and poverty-stricken, and that its fans were, seemingly, nothing more than a pack of blood-thirsty Neanderthal throwbacks.

But, as a cultural phenomenon, Rocky was also drawing on an improbable, real-life saga that had already captured the attention of millions including many who were not usually fight fans – the “Rumble in the Jungle” in Kinshasa, then Zaire, the championship fight that took place forty years ago on 30 October 1974. In that fight, Muhammad Ali, an apparently world-weary, thirty-two-year-old fighter, recaptured the world heavyweight boxing title from George Foreman – a man seven years younger than Ali – in the eighth round of what by any measure was an extraordinary exhibition of pugilistic skill.

By the time this fight would take place, Ali had already lost his title by administrative fiat when the boxing commission stripped him of his crown, after the US government had charged him with refusing to be registered for the military draft in the midst of the Vietnam War. Ali, of course, had thoroughly roiled the waters when he had said, “Man, I ain’t got no quarrel with them Viet Cong”.

But, by 1970, he had successfully regained a boxing license and had fought comeback bouts against Jerry Quarry and Oscar Bonavena as part of a strategy to regain the heavyweight championship from the then-undefeated Joe Frazier. In the 8 March 1971 fight between Frazier and Ali, labelled “The Fight of the Century”, Frazier had won in a unanimous decision, after punching Ali almost senseless to the ground in the 15th round, after which Ali barely survived to the final gong.

Watch: Ali vs Frazier, 1st fight

This forced Ali to take on numerous other contenders for several years, losing to Ken Norton and then slowly plotting his way back in order to score enough points for a new title shot. In the meantime, Frazier met a steamtrain called George Foreman (Heavy weight champ from 1968 Olympic Games; Frazier won in 1964, while Ali was a light-weight champ in 1960). Foreman destroyed Frazier 1973 in Kingston, Jamaica in the so-called “The Sunshine Sundown”, knocking him six times to the ground, until the referee mercifully stopped the match in the second round. After Ali also defeated Frasier on points early in 1974, the stage for him to challenge for the title has finally arrived again.

Watch: Foreman destroys Frazier in Kingston, Jamaica

The two men – Foreman and Ali – presented starkly different public personas. Ali was the voluble, politically controversial, highly public figure who had been an Olympic boxer under the name Cassius Clay and who then shucked off what he called his “slave name” to become Muhammad Ali when he embraced Islam. Foreman, meanwhile, took great pride in his rise from what he called “the gutter” – first from opportunities in the War on Poverty’s Job Corps program for ghetto youth, and then via his skills and triumphs as a boxer, including his Olympic gold medal. In the lead-up to their match, Ali unmercifully taunted Foreman, trying to portray him publicly as slow-witted – and something of a racial Uncle Tom as well.

The man behind the fight was boxing promoter Don King, with that sui generis hairstyle. King’s tonsure looked something like what an Afro would be if its bearer had placed his hands on a tesla coil electricity generator. King had originally labelled this fight “From the Slave Ship to the Championship!” that is, until Mobutu Sese Seko, Zaire’s president, had learned of this and had all the posters confiscated and burned. Mobutu had personally offered the two fighters $5 million each for their participation as a marketing device to attract world attention to Zaire’s natural resources (and presumably to deflect attention away from Mobutu’s more kleptocratic impulses). The fight became Africa’s first heavyweight championship match.

Photo: The match poster bore the original date set for the match, 25 September 1974, but it was postponed to 30 October after Foreman’s injury.

The event was one of Don King’s first ventures as a professional boxing promoter. To achieve this match-up, King pulled together a consortium that involved a Panamanian investment holding company, the Hemdale Film Corporation (founded by film producer John Daly and actor David Hemmings), Video Techniques Incorporated of New York, and Don King Productions. Ultimately, while King’s is the name most closely associated with this fight, Hemdale and Video Techniques Inc were the official co-promoters of “The Rumble in the Jungle”.

Attempting to give some greater metaphysical meaning to his own motives for the match, Ali wrote about it later, saying, “I wanted to establish a relationship between American blacks and Africans. The fight was about racial problems, Vietnam. All of that… The Rumble in the Jungle was a fight that made the whole country more conscious.”

On the day of the fight, at 4am, around 60,000 spectators gathered outdoors in the Stade du 20 Mai. The fight took place at that highly unusual time so it would be broadcast in prime time in the US. For the Kinshasa crowd, Ali was clearly the favourite as the partisan crowd loudly chanted, “Ali, boma ye!” (Ali, kill him!).

Watch: Rumble in the Jungle

Before the fight had begin, Ali had told his trainer, Angelo Dundee, and his fans that he had a secret plan for dealing decisively with Foreman. This also played to Ali’s continuing taunts of Foreman. But, when the first bell rang, Foreman began assailing Ali with his trademark sledgehammer blows. Responding to Foreman’s punches, Ali backed up against the ropes, wrestling with Foreman, blocking as many punches as possible with his arms and shoulders; hoping he could wait out the younger man. (Afterwards, Dundee called Ali’s strategy the “rope-a-dope,” because he was “a dope” for using it, even though it worked out very for him.)

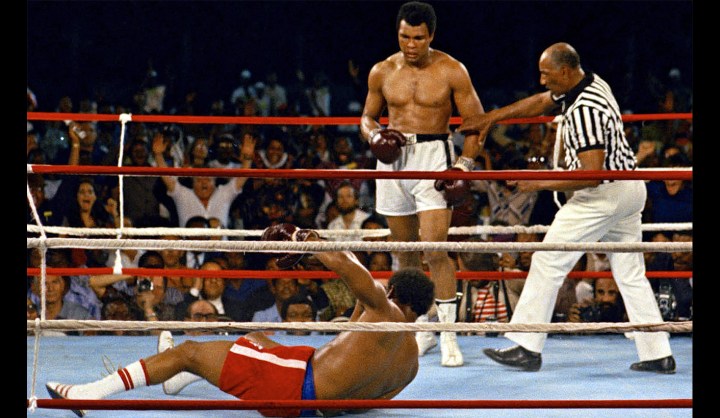

By round five, Foreman was starting to tire and his face had become increasingly damaged by some of Ali’s fast jabs and crosses. Then, three rounds later, like a “bee harassing a bear” as one reporter named this strategy, Ali moved away from the ropes and gave a run of quick punches that confounded the increasingly exhausted Foreman. Ali then delivered a hard left and then a right. The two punches buckled Foreman’s legs and the soon-to-be-former champ fell to the mat. The referee counted Foreman out – with just two seconds left in the round. The result was a stunning, unexpected victory for Muhammad Ali and an event that has been termed, “arguably, the greatest sporting event of the 20th century.”

His dramatic return as champion in the fight in Zaire forty years ago made him only the second dethroned champ ever to regain his championship belt, after Floyd Patterson.

In 1975, Ali won another epic fight, this time with Joe Frazier in “The Thrilla in Manila”. Incidentally, he later said that the 14th round of that match was his most difficult moment ever, when he thought he was about to die. You can imagine his happiness when Frazier didn’t manage to get up as the 15th round was starting, handing Ali another famous victory.

Watch: Thrilla in Manilla

Thereafter, before he retired from the ring, Ali’s skills and reflexes had deteriorated, but he was still the heavyweight champion until 1978, when Leon Spinks defeated him. Astonishingly, he regained his title for an unprecedented third time, beating Spinks in a rematch. Later fights were less successful, however, as he was beaten by Larry Holmes in 1980 and then by Trevor Berbick the following year. Foreman, meanwhile, retired three years later, but he then came back a decade later to reclaim the title – becoming the oldest heavyweight champion in the history of professional boxing at the age of 45.

Nowadays, Foreman is a minister and has a ranch in Texas and he has five daughters and five sons – and all of them are named George. Really. Foreman has also become the wildly popular pitchman for those patented George Foreman indoor BBQ grills. And Ali? While nearly incapacitated by Parkinson’s disease, he has become a hero whose fame has transcended the world of boxing – or even sports in general – to become a folk hero for black (and many white) Americans – as well as to a broad sweep of the African diaspora and beyond. Foreman and Ali, meanwhile, have become close friends. About this friendship, Foreman has said, “We fought in 1974, that was a long time ago. After 1981 we became the best of friends. By 1984, we loved each other. I am not closer to anyone else in this life than I am to Muhammad Ali.”

The fight remains a firm sports fans’ favourite – it is repeated several times a year on the ESPN Classic television network and has been a significant cultural influence as well. The events before and during this fight are part of the Oscar-winning documentary, When We Were Kings – which features brilliant Miriam Makeba; while the biopic, Ali, has the fight as the film’s climax.

Author Norman Mailer, who had covered the fight, wrote the book, The Fight, placing the fight in the broader context of Mailer’s own views of black American culture. Another author, George Plimpton, was also at the fight, covering it for Sports Illustrated, and he spent much of his book, Shadow Box, describing the fight. Finally, Hunter S Thompson was also there to cover the fight for Rolling Stone, but, inevitably it is said, Thompson “chose to float in his hotel pool, a bottle of hooch in hand, while the great fight took place, and he was unable to file anything,” according to Time magazine.

For sports fans, according to a 2002 UK poll by Channel 4, the UK public placed this fight as seventh on a list of the hundred greatest sports moments. And in the US, the ABC television network’s “Winners Bracket” says the fight has been named the greatest moment in the history of ABC’s Wide World of Sports. DM

Main photo: The match was over in the 8th round.

Read more:

- Rumble in the Jungle: the night Ali became King of the World again at the Guardian

- An Interview with George Foreman “I Was Hungry Most of the Time”, at the Prince Georges Post

- Muhammad Ali wins the Rumble in the Jungle at the History.com website

Become an Insider

Become an Insider