Maverick Life

Steve Newman: Still living it, after all these years

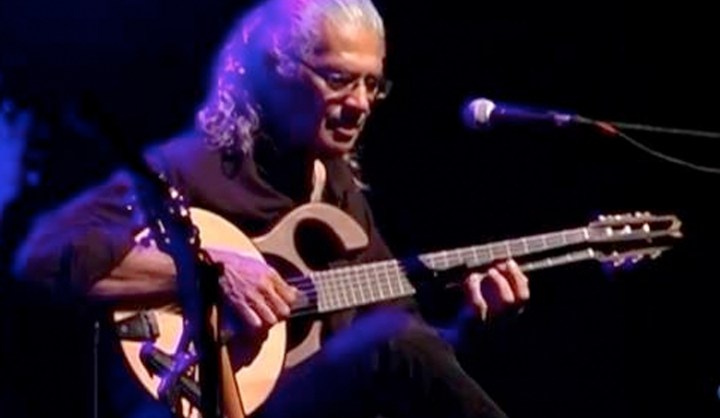

Veteran guitarist Steve Newman was in Cape Town for the duration of the inaugural Fringe Festival and made some of the last four decades’ familiar magic on stage. And there’s a bonus: Tananas will be re-forming. MARELISE VAN DER MERWE caught up with him.

It’s not enough just to be creative, says Steve Newman. “You have to live creatively.” To this end, he lives in the countryside – in Uniondale – with his wife, where he collects rainwater, practices yoga, lives sustainably and homeschooled his five children (the youngest is 15).

Sixty-two-year-old Newman has been a familiar face on the music circuit since 1976, and met luthier Mervyn Davis not long after. Davis – who incidentally also makes guitars for Jonathan Butler – first made Newman a guitar in 1979, which he still uses today. “I can wreck it today and he’ll give it back to me tomorrow,” Newman says, speculating that his guitars will last as long as he does – or, perhaps, as long as Davis does. It’s been more than 35 years; long may it last.

Newman owns eight or nine guitars – he doesn’t confirm the exact number – and the two favourites are the nylon-string survivor from 1979, and another custom-made SmoothTalker from 2004. This one, Davis presented to him as an idea: it’s got an mbira built onto it, on the front, as well as a scratchplate, for creating different musical effects. The design was the result of a casual conversation between Davis and Newman some years before; Newman mentioned that it would be great to have a guitar and mbira in one, and Davis promptly presented him with the idea brought to life. It’s the instrument he used at a gig at The Crypt during the Fringe Festival; it held the audience spellbound.

Not that this always happens, Newman says. Last night he played with All in One at the Centre for the Book which, he said, was incredible – the show also featured Hannes Coetzee, who plays with a spoon in his mouth, and a minstrel troupe. “It was a great night,” he says. “People really got it, which doesn’t always happen. Most people want to hear something American, something familiar.”

Watch: Hannes Coetzee

And when that happens, there’s no connection, no magic. In these circumstances, Newman says, there’s not much you can do – “you just play your best”.

“I’ve had people come up to me after a show and ask, ‘Don’t you play any George Benson?’” he says. “They don’t want to hear what you have to offer. But hey, they have what they really love. What I do isn’t exactly mainstream, so I try to keep it interesting.”

For Newman, this involves keeping a finger in every imaginable pie. Ask him what he’s working on and it elicits an answer too long to write down. With 20-odd albums under his belt already, the list of current and future projects literally goes on for pages, including a reunion with the hugely popular Tananas’ Ian Herman, now that they have met a bass player they are “excited about”.

What strikes me about Newman is a certain humility; he is aware, even if subconsciously, that he has to work to maintain an audience and he doesn’t expect fans to come flocking if he’s not putting in the spadework. To an extent, he verbalises this.

Listen: Tananas, Hard Hat Jive

“There’s no such thing as fans,” he says. “There are friends. You make friends along the way. Fans are for rock ‘n’ roll. I’ve just got to keep going. I’ve been doing this since 1976, and often if you stay away for a while and then come back, that works – people do remember you. I’ve been lucky to make some friends along the way.”

The same attitude applied to accessing Newman as a journalist, a refreshing reminder of a culture amongst musicians that is dying out. As a reporter, one too-often encounters two brands of artists: those who are desperate to speak to you and make a name for themselves, and those who already have a name, and are impossible to pin down. For Newman, it was not so. There was no manager, no publicist, no red tape; only Newman and his son Jivan, selling CDs and chatting to audience members. And upon turning up for the interview, the door was opened by a relaxed Hilton Schilder, who simply put his dog on a leash and went about his business as the interview went on.

My word, I tell Newman. Real human beings. Yes, he agrees. This is why he prefers Facebook, too, rather than Twitter or his website. It’s more of a community and more interactive. “There’s more direct access,” he says. “You don’t have to deal with managers and shit.”

It’s a culture that survives among some of the older local musicians; those who have been around the block a few times and, perhaps, aren’t so celebrity-driven. But, says Newman, this isn’t lasting. “It’s got to do with churning out mediocre stuff, because that’s what sells,” he says. “What we do is on the fringes, and we don’t make much money, but at least the money comes directly to us – instead of the musician being at the end of a long line of people.

“Among the younger musicians, it’s all standardised,” he adds. “There’s a focus on European and American music. Our kids are being taught that in universities and technikons. But they should be taught the treasures we have here. They should be exposed to Indian music, and flamenco. That’s how I operate.

“I don’t want to copy someone else’s culture, but I want to put that spice in there.”

Is a cultural identity important, then? Well, no. “We try to draw from sources other than just the European and American. I’m a citizen of the universe; that’s the only identity I’m willing to admit to. I’m a universal being, and that must be reflected in your music. Well, not must. But it might.”

It’s an attitude that has led him to collaborate with international artists as diverse as Paul Simon, Sting and Youssou N’Dour. Despite the far-reaching influences, however, Newman discovered music much closer to home: as a small child, through the magical sound of his parents’ parties.

“My parents used to have parties,” he explains, “and they used to hire bands, which I would then hear playing. My brother played drums, too, but not a lot. My dad used to play guitar, but had given up by that time. He tried to show me guitar, but it didn’t really make sense to me at that time.

“But there was a mechanic in our neighbourhood in Brooklyn. He played classical guitar. And people used to gather at this movie hire shop near the bus stop and listen to music, and talk about music. And then one day Mickey Higgins – the mechanic – invited me over to tea, and said he wanted to show me something. It was a book about classical guitar, and he lent it to me. I read it and slowly started learning to play guitar, and I started to move away from Pink Floyd and the other stuff I was listening to in high school. And then – this was in the late 70s – I started writing my own tunes.”

The first album he wrote was modest, “Just three or four tunes plus a few polkas, some sambas, a bit of everything” – but it snowballed from there and Newman discovered an enduring love of music from all over the world. He has – with collaborators and solo – travelled, most recently, to New Zealand, the Seychelles, Holland, Hong Kong, Sweden, Spain, the United States. “Basically everywhere,” he says, “except Canada and South America.”

Why not South America, though? Given that so many of his musical heroes hail from there? The answer isn’t clear. Attempts at both Canada and South America may be in the pipeline, he suggests, if the right combination of opportunity, finances and music festivals line up. “Now that Tananas will be re-forming, we will be travelling a lot more,” he says.

Tananas suffered a devastating blow when bassist Gito Baloi was murdered in 2004. Now, the surviving members have found a new bass player whom they feel enthusiastic about, and Newman and drummer Herman will collaborate again. There is also an ambitious 10-piece musical project Newman works with that “only happens occasionally” due to its size and scope, as well as regular collaborations with singer Lu Dlamini and tabula player Ashish Joshi respectively.

Watch: Steve Newman and Lu Dlamini

Additionally, Newman also records with All in One (Schilder and Errol Dyers) and has a new album out, entitled All Living Beings, which is available for download through iTunes. And, of course, there is the return of the favourite performances with Tony Cox.

“We’ll be returning to lunchtime shows next year at the Space Theatre, just like it was back in the day,” he says.

Watch: Steve Newman, Tony Cox and Syd Kitchen

So what does he see in the future? More of the same, he hopes, although the work – and the musical platform – is “always evolving”. Independence, he maintains, is paramount. He tells an anecdote about a friend who was a struggling artist until, quite by chance, Madonna heard one of his songs and it was used in an advert. “Now he’s got his own studio, guitars on his wall, the works,” Newman says. “It’s great when that happens, and it does happen once in a while. If Johnny Clegg or Ladysmith Black Mambazo have a song used in a movie, that’s great. But that’s not why I’m in music.

“If I were a millionaire, the music might change.” DM

Follow Steve Newman on Facebook.

Read more:

-

Steve Newman review on Home Grown Music

Photo: Steve Newman.

Become an Insider

Become an Insider