South Africa

Analysis: Politics of paranoia, SA style

Last week, there was a massive spat in Parliament, when SACP/ANC's Buti Manamela likened EFF's Julius Malema to Hitler. We thought you might want to re-read this analysis by J. BROOKS SPECTOR, which points out that the comparison with Benito Mussolini would be much closer to reality.

One of the most famous and influential essays of American political analysis remains historian Richard Hofstadter’s “The Paranoid Style in American Politics”. In the opening words of his 1964 essay, Hofstadter had written, what he termed “the paranoid style in politics” “had been around a long time before the Radical Right discovered it – and its targets have ranged from ‘the international bankers’ to Masons, Jesuits, and munitions makers. American politics has often been an arena for angry minds.”

Hofstadter added, “In recent years we have seen angry minds at work mainly among extreme right-wingers, who have now demonstrated in the Goldwater movement how much political leverage can be got out of the animosities and passions of a small minority. But behind this I believe there is a style of mind that is far from new and that is not necessarily right wing. I call it the paranoid style simply because no other word adequately evokes the sense of heated exaggeration, suspiciousness, and conspiratorial fantasy that I have in mind…. the idea of the paranoid style as a force in politics would have little contemporary relevance or historical value if it were applied only to men with profoundly disturbed minds. It is the use of paranoid modes of expression by more or less normal people that makes the phenomenon significant.”

Hofstadter went on to argue, “Of course this term is pejorative, and it is meant to be; the paranoid style has a greater affinity for bad causes than good. But nothing really prevents a sound program or demand from being advocated in the paranoid style.”

Hofstadter had written this essay to explore the rise of Senator Barry Goldwater to become the 1964 Republican presidential nominee. In looking at that phenomenon, he cast backwards to find a psychological similarity with the shrill anti-communist, anti-intellectualism of McCarthyism of a generation earlier. He then carried these observations back through American history, describing a style of political discourse that tapped into fears of secret conspiracies bent on destroying American life. Hofstadter was careful to point out what he identified as the paranoid style was not limited to solely one side of the political spectrum. Rather, he observed, it just as easily could come from any part of the ideological continuum. He pointed to historical examples of movements that built upon political movements that marshalled a profound fear of the collusion of big business and banking interests under the sway of nefarious foreign influences, that were allied with domestic politicians – all part of a plan that had been deliberately designed to crush the lifestyle of America’s sturdy independent farmers.

Now of course Hofstadter couldn’t discuss the Tea Party’s ideology and the groups associated with it since his essay is nearly fifty years old. This latest movement arose nearly a half century after the rise of Barry Goldwater’s so-called “silent majority,” but its motive power seems to have drawn on many of the same sources.

Recently, this writer examined survey research on the ideas (and fears) of those well-disposed to the Tea Party in The Daily Maverick in “Stanley Greenberg’s reading of Tea Party leaves: anger, fear, uncertainty.” Drawing on the survey data, this writer noted that “many Americans simply were not ready for the election of a mixed-race president, they weren’t ready for gay marriage, the transformation of American demographics in the past thirty years, and, in the economic sphere, they were not prepared for the increasingly harsh impact of globalisation on working and middle class families and incomes – let alone the on-going fallout from the 2008 financial crisis.”

The data pointed to the fact that for such supporters, individuals, “the very culture of the nation is running away from them and, on top of everything else, they believe they have lost the ability to control their government…. It isn’t just avowed Tea Party fans of course who have some of these feelings. It is broader. A dislike – sometimes even a loathing – of government has been growing at an astonishing rate among those identifying themselves as Republicans.”

But of course this so-called paranoid style has not been limited to America. Archetypical fascist movements in twentieth century Spain, Germany, Italy, Romania, Argentina, and Hungary, among many others, were also built around many of the same themes. For these movements, there were insidious domestic enemies – teaming with international co-conspirators – intent on victimizing the homeland and thwarting the nation’s ability to gain (or regain) its rightful place internationally. And in the past couple of years as well, throughout Europe and beyond, in the wake of the 2008 financial crisis and still-continuing international pressures on various financial systems and the knock-on effects on society, there have been a growing number of parties such as the UKIP in Britain, Italy’s Five Star movement, and Greece’s Golden Dawn Party that also share elements of Hofstadter’s “paranoid style” politics – on both the left and right sides of the political landscape.

And inevitably this brings us to South Africa as well. Does the emergence of the Economic Freedom Fighters epitomise this trend or tendency as well? The EFF’s core argument is the continuing exploitation of a poor majority by a resilient power structure that brings together money and political potency and continues to hold the vast majority of the nation’s productive land and virtually all other economic resources – and is in league with foreign economic agents. And all of this is designed to keep the poor and dispossessed firmly in their places and under the heel of a rulers’ boot.

The potent thing about this view is that there are quite obviously important elements of this picture that are perfectly true. And it is certainly not much of a stretch to nod agreement with the EFF’s argument that the national economy remains fundamentally skewed away from the needs of the majority subsisting at the lower rungs. It is this quality that makes a political siren song like that of the EFF so appealing.

Or as the EFF’s own declaration explains the new party’s perspective: “The EFF is a South African movement with a progressive internationalist outlook, which seeks to engage with global progressive movements. The EFF draws inspiration from the broad Marxist-Leninist tradition and Fanonian schools of thought in their analyses of the state, imperialism, culture and class contradictions in every society…. Economic Freedom Fighters provide clear and cogent alternatives to the current neo-colonial economic system, which in many countries keep the oppressed under colonial domination and subject to imperialist exploitation. We believe that the best contribution we can make in the international struggle against global imperialism is to rid our country of imperialist domination.”

The potent thing about this picture – after making due allowance for its hyperbolic, semi-digested Marxism – is that there are obviously important elements in it that have the ring of truth. And it is not much of a stretch to agree with the EFF’s argument that the rewards of South Africa’s economy remain fundamentally directed away from the majority that exists precariously on the economy’s lower rungs. As a response, the EFF’s declaration offers, “Massive protected industrial development to create millions of sustainable jobs, including the introduction of minimum wages in order to close the wage gap between the rich and the poor, close the apartheid wage gap and promote rapid career paths for Africans in the workplace.” It is promises like this that may make the political siren song from the EFF so appealing.

The EFF’s founder and primary leader, Julius Malema, is an extraordinary speaker who seems to be able to preternaturally touch the inner feelings of many of those to whom he appeals. Helping define Malema’s appeal, Rhodes University’s lecturer Richard Pithouse argues, “The political theatre that Malema performed at the court when his hate speech case was heard in April 2011 did evoke shades of Mussolini in many people’s minds and certainly created the impression that his conception of power is rooted more in force than consent.”

Mussolini is, in fact, a fascinating comparison to make. Originally an eclectic socialist, by the time of his 1922 “March on Rome”, Mussolini had shifted into being a near-theatrical advocate of an Italian nationalism that tapped into Italian yearnings for a bigger national role on the world stage. However, he still retained elements of his earlier socialist leanings in his public utterances in his calls for aiding the lower classes. In comparison, and similarly theatrical in his public presence, Malema also appears to have shifted many of his political positions, in his case leftward, even as he has retained – and even enhanced – elements of a Robert Mugabe-style African nationalism in his public rhetoric.

Late last year, for example, the BBC could observe, “Mr Malema is exploiting the killings [at Marikana] to reinforce his image as the champion of poor black South Africans, though he also has some support in black business circles, says Johannesburg-based political analyst William Gumede. He moves with ease between the two groups, toyi-toying… at rallies in shack settlements, before slipping away to leafy suburbs for all-night parties with the nouveau riche. ‘It’s difficult to put Mr Malema in a box. He uses rhetoric that suits him at a particular time,’ says Mr Gumede. He argues that Mr Malema is similar to politicians in Zimbabwe’s Zanu-PF party, led by President Robert Mugabe. ‘They express conservative views on social issues [for instance, gay rights]. When it comes to economics they use socialist rhetoric but they are, in fact, capitalists who use the state to advance their own political and business interests.’ ”

And in this regard, Pithouse comments, “Malema only turned to popular struggle in search of a constituency when the ANC turned on him. In COSATU’s estimation he was on the party’s right wing before his relationship with Zuma broke down…. The fact is that nationalisation was [also] a key plank in the original programme of the Nazi party. It has also been used by various appallingly authoritarian regimes that have presented themselves in the language of the left, including the North Korean monarchy supported ‘unapologetically’ by the ANC Youth League under Malema.”

Pithouse goes on to say, “Malema’s politics… mobilises the language of Stalinism to approach the citizenry as ‘the masses’, as a kind of battering ram wielded by leaders. The fact that this mode of politics may offer a route into a certain kind of respect for some young men cast adrift from hope in a society grounded in contempt for their equal humanity does not make it progressive.” Pithouse adds that the EFF’s proposals, with their authoritarian texture have “certainly created the impression that his conception of power is rooted more in force than consent.”

Returning to Hofstadter, “respectable paranoid literature not only starts from certain moral commitments that can indeed be justified but also carefully and all but obsessively accumulates ‘evidence.’ The difference between this ‘evidence’ and that commonly employed by others is that it seems less a means of entering into normal political controversy than a means of warding off the profane intrusion of the secular political world. The paranoid seems to have little expectation of actually convincing a hostile world, but he can accumulate evidence in order to protect his cherished convictions from it…. We are all sufferers from history, but the paranoid is a double sufferer, since he is afflicted not only by the real world, with the rest of us, but by his fantasies as well.”

And then just the other day, the nation was subjected to a remarkable public outburst by the ANC’s Deputy President, Cyril Ramaphosa at a pre-campaign campaign rally in the northern part of the country. His comments combined both elements of Hofstadter’s thesis on the ill-tempered resentments of that “paranoid style” and “dog-whistle politics”- South Africa-style. Dog whistle politics are, of course, those explanations that speak volumes to a politician’s supporters or would-be supporters, that both reinforces their worldview and aims to rally their enthusiasm, even as those explanations sail right past anyone else not already in tune with such a siren call.

The term “dog whistle” comes from the ultra-sonic whistle people often use to capture the attention of a working dog, that only the dog can hear. When the whistle blows, the dog’s head snaps sharply in the direction of the sound, even as it is apparently silent to humans. When Ramaphosa told voters in Seshego that failing to support his party would open the flood gates for a literal return of apartheid, he was following – and accentuating – the contours of an already-existing, popular worldview, sending out those ultra sonic dog whistle sound bites that holders of such a weltanschauung would appreciate instinctively, identifying with the very truths that have been wounding them and holding them down for as long as memory exists. This may be very good politics, but it is probably rather less so as a citizenship lesson.

As South Africa’s campaign season kicks into higher gear, the leadership of the ANC may well hold concerns their mandate and substantial majority is coming under challenge among the underclass, as well as with those who increasingly expect – or demand – more efficiency and effectiveness from their government. It is likely, therefore, the country will witness more such political appeals, Hofstadter-style, along with increasingly strident dog-whistles to the faithful. How the electorate responds to all this will be increasingly important to watch. DM

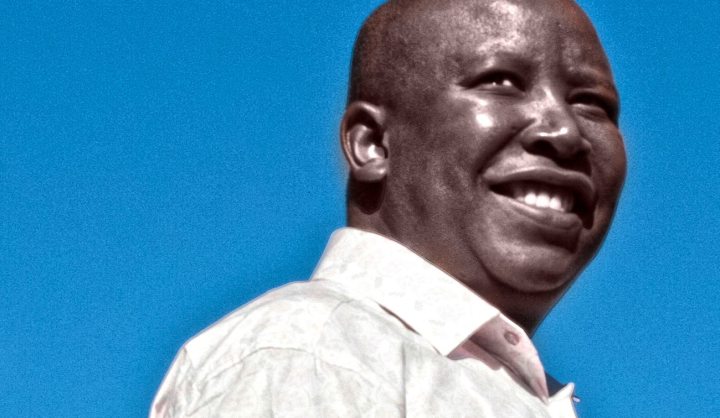

Photo: Julius Malema (Jordi Matas)

For more, read:

- “The Paranoid Style in American Politics” in Harpers Magazine;

- “Stanley Greenberg’s reading of Tea Party leaves: anger, fear, uncertainty” in The Daily Maverick;

- “Why Ramaphosa’s ‘boer’ remarks cannot be lightly dismissed” (a column by Sipho Hlongwane) at Business Day;

- “Separate and unequal: Apartheid’s legacy lives on” at the Independent (UK);

- “Rhetorical” (promo of a drama from South Africa, on tour in the UK, in which a key character is a fictionalized version of Julius Malema) at UKArts.com;

- A YouTube extract from “Rhetorical”;

- “It’s Just a Jump to the Left, And Then a Step to the Right” (essay by Richard Pithouse at the SACSIS.org website (SA Civil Society Information Service)

- “Malema, Marikana and Mugabe” at the BBC;

- “Julius Malema rises to speak for the ‘betrayed’ ”, a column by Setumo Stone for Business Day;

- Declaration at the EFF website;

- About us at the EFF website.

Become an Insider

Become an Insider