“It’s such a fine line between stupid and clever,” David St Hubbins, This is Spinal Tap.

A long, long time ago in a galaxy far, far away, long before the collapse of the Berlin wall, Apartheid and global capital markets, South Africa used to export a different kind of music. It was, in many ways, an age of innocence (well, it never really was, but bear with us). In an apparently less complicated, binary universe, it was the likes of Ladysmith Black Mambazo, Johnny Clegg and Savuka, Hugh Masekela, Ray Phiri and others that somehow came to represent the collective heart, soul and psyche of the country.

The music then was still distinctive. It was instantly recognisable as a “South African” sound, regionally and linguistically struck from the noble struggles of the time.

But the world in 2014 is a decidedly different place. The two competing ideologies of Western Liberal Democracy vs. Communism no longer exist. Today the world has surrendered pretty much entirely to global market forces, whether in the guise of a free market or state capitalism and corporatism. The boundaries of everything with we think, know and consume have shifted – in fact there are no boundaries. We are global consumers – well, at least those of us who have jobs and access to credit and the Internet.

It is no accident then that in 2008, in the slipstream of the cataclysmic crash of the stock market, Die Antwoord stepped into the vacuum and almost miraculously and instantly found fame and traction with their debut offering, “$O$” (available free online), among a large cohort of the world’s recently financially brutalised middle classes.

There is an observation that Slovoj Zizek, one of the world’s most engaging contemporary philosophers and cultural commentators, makes about James Cameron’s Hollywood blockbuster, Titanic, and that is perhaps pertinent to and might help explain the contemporary appeal of Die Antwoord to some.

In his thrilling documentary, A Pervert’s Guide to Ideology, the Slovenian-born Zizek unpacks the encounter between Kate Winslet’s character, the “high society” first-class passenger, Rose DeWitt Bukater, with the poor and homeless, Jack Dawson (Leonardo di Caprio), who is travelling third-class. Zizek remarks that in the film, Di Caprio’s character acts as a “vanishing mediator” for the Winslet character. Jack’s only function, Zizek says, is “to restore her sense of identity and purpose in life, her self-image (quite literally, also; he draws her image); once his job is done he can disappear.”

He cites instances in other films where a young rich person in crisis “gets his or her vitality restored by a brief and intimate contact with the full-blooded life of the poor”.

And it is this function, too, that Die Antwoord fulfills for the generally wealthy, (dare we say white) middle-class fans in the Northern hemisphere who flock to their live concerts enthralled by the “rough trade” and “white trash” aesthetic the duo, their music and their entire artistic construction provides.

Die Antwoord offers a safe and exciting encounter and flirtation with poverty, violence and life at society’s edges without fans ever really having to engage with the realities of fellow human beings who actually are forced to live this way.

The fact that their 'art' has been forged in South Africa, a geographical space that has lived with a brutal and institutionalised 99 percent/1 percent divide long before it sucker-punched the rest of the world in the face, is what renders Die Antwoord’s work problematic to some local commentators.

There have been various lucid critiques of Die Antwoord by South African writers including that the duo employs “blackface” and has expropriated Afrikaans working-class and well as coloured and black “culture” and experience for commercial gain.

And therein lies the conundrum. Do we dislike the distinctly middle-class Watkin Tudor Jones and Yolandi Visser because we believe them to be “fake” or somehow “inauthentic” or do we acknowledge their “art” because it perversely prompts and mirrors for us the greater contemporary human condition? And is it all simply a matter of taste?

In Die Antwoord’s world there are no longer any rules of engagement and their dark and at times repulsive genius lies in the very fact that we are attracted to it all – like passing fresh road kill. We seek the ugliness, the profanity, the cruelty and the violence that we know underpins political, social and cultural power in the world, but we don’t have to actually LIVE it.

Like the soma offered to neutralise the citizens in Aldous Huxley’s 1931 apocalyptic novel, Brave New World, Die Antwoord serves as a sort of cultural tranquilliser. While Die Antwoord’s music itself is groundbreaking and original, in the end they are merely Zizek’s “vanishing mediators”.

We live in an age of extreme expropriation from political parties and leaders such as the right-wing Dutch populist Pim Fortuyn (assassinated by a vegan in 2002) to even our dear Julius Malema, himself no stranger to borrowing left-wing symbols of dress, performance, posturing and rhetoric.

The rules of engagement have altered inexorably and Die Antwoord provides anthems for some who find themselves in this disengaged new world.

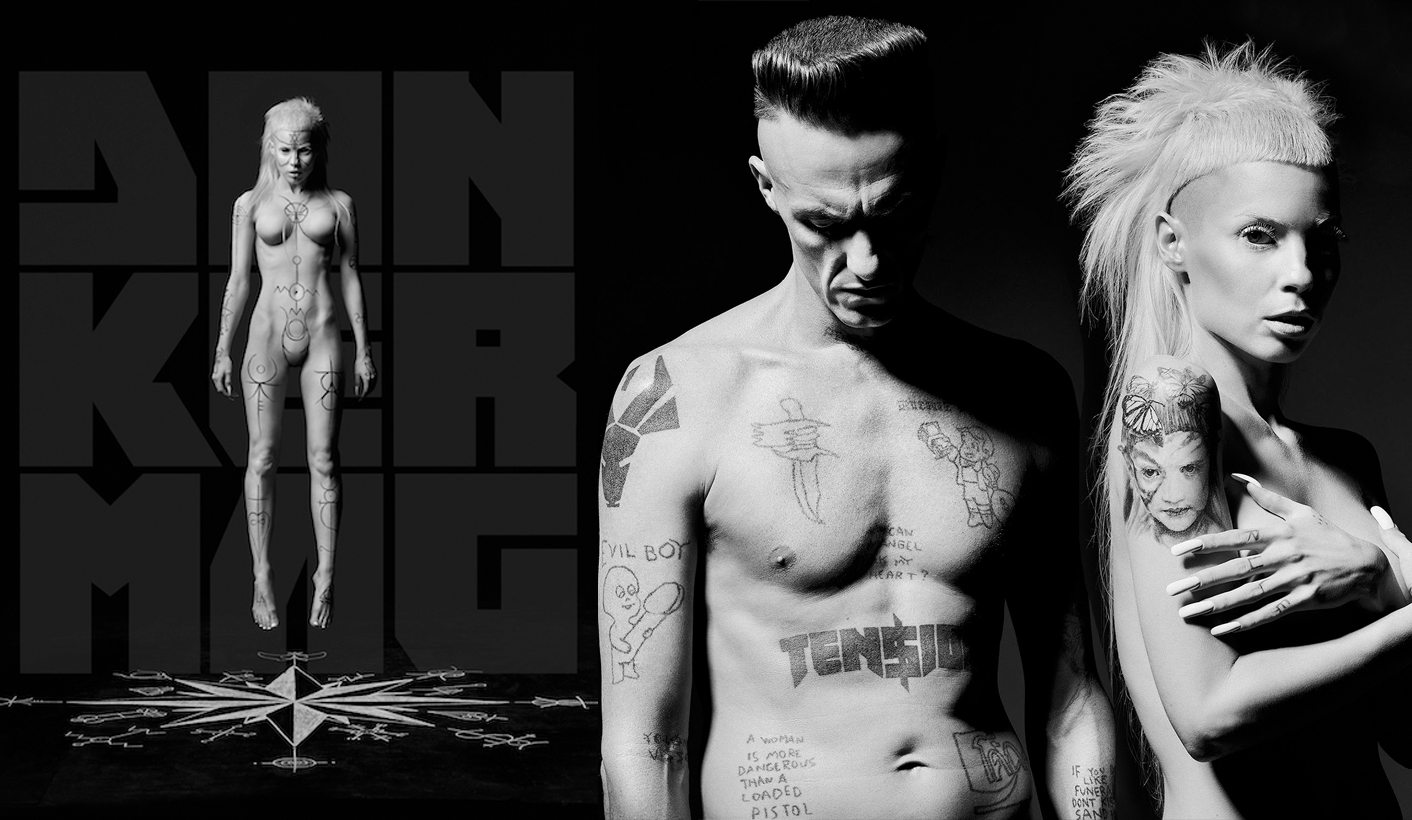

Donker Mag, Die Antwoord’s third studio album, consists of 16 tracks, some of them released earlier, including “Cookie Thumper”, continuing Die Antwoord’s ongoing flirtation with The Number prison gang culture,“Pitbull” (directed by Ninja with visuals reminiscent of Skrillex’s Ragga Bomb) as well as “Zar”, Ninja’s riff on his collapsed South African identity.

Watch: Die Antwoord - "Cookie Thumper"

In “Happy go Sucky Fucky,” Die Antwoord spells out an anthem for our times; “We live the life we love/we love the life we live/Don’t need no one fucking up our shit/Okay, bitch/Get the fuck off me/I’ll freak you the fuck out/Cause' I chose to be free/Fuck your rules/Who are you to tell me/What I can and can’t do fuck you bitch/You just want to be me/”.

I could well imagine a variation of it being sung at EFF rallies.

The fact that Dior opted to use Die Antwoord’s “Enter the Ninja” as a soundtrack for their new perfume – appropriately titled “Addict” (as an olfactory companion piece no doubt to “Envy”, “Obsession” and “Narcissus”) (view video here) only serves to deepen the quite conventional relationship between Die Antwoord and the commodification of almost every aspect of modern life, including dispossession and poverty.

Watch: Addict by Christian Dior (Director's cut)

Perfume, like designer clothes, provides consumers with the acceptable aroma of material wealth and success to accompany all the other outward accoutrements (and who cares if they’re made by children in sweat shops).

And so it is in many ways that Die Antwoord are hugely predictable and hardly revolutionary producers of music and cultural commentary. That they have become commercially successful in the process is of course, perfectly in keeping with the zeitgeist; it is evidence of the triumph of market forces.

Watch: Die Antwoord - "I Fink U Freeky" (David Letterman Show)

What Die Antwoord does make visible, in an acceptable form, is the ugliness and chaos of a world centered on accumulation and material wealth, where political leaders blatantly lie, cheat and steal and where there appears to be no real “moral” centre. It is all extremely bleak, atomised and appropriate. In the end, though, Die Antwoord lets everyone off the hook. Their music and their art does not inspire in the listener any real rebellion against injustice or the status quo, merely full cock-sucking immersion and acceptance.

Rolling Stone and Time Magazine have both given Donker Mag rather muted reviews, suggesting the Zef rappers are much of a muchness and are in danger of becoming a mere gimmick.

The upside of Die Antwoord as a South African cultural export is that we can’t be charged with not being ahead of a world cultural curve - even if it comes complete with urine, tattoos, hard-ons, profanity, drugs and the general excess we expect from all good consumers. DM

Photo: The cover of Die Antwoord's Donker Mag; Watkin Tudor Jones and Yolandi Visser.