Maverick Life

Don’t let me be misunderstood: FW de Klerk and the burden of history

American filmmaker, Nicolas Rossier, spent three years working on “The Other Man – FW de Klerk and the End of Apartheid in South Africa”. The film will have its world premiere at the Durban International Film Festival on 19 July. But will South Africans learn anything new or feel any differently about Apartheid South Africa’s last white president? By MARIANNE THAMM.

There are few historical figures – who spring immediately to mind, that is – who have found themselves both on the wrong and the right side of history at the same time. South Africa’s last white president, Frederik Willem de Klerk, or FW as he is known locally, is one such figure.

In 1993 De Klerk was jointly awarded with Nelson Mandela, the Nobel Peace Prize for their work, as the committee termed it, in bringing about the “peaceful termination of the Apartheid regime, and for laying the foundations for a new democratic South Africa.” The decision to award the prize jointly was not without controversy, many believing that the two leaders were not of the same calibre, depth or significance. Mandela, many thought, should have been the sole recipient.

While inside the country FW De Klerk’s reputation is far from being unequivocally established – familiarity breeding contempt and all that – his legacy as a man willing to surrender power for the greater good of a fractured country is not in dispute.

Whether De Klerk was pushed by external political and economic forces or propelled by an inner Damascene conversion in initiating the profound changes in 1990 that would lead to the surrender of power of a white minority government, are some of the issues Rossier attempts to explore in his film The Other Man – FW de Klerk and the End of Apartheid in South Africa.

Watch: ‘The Other Man – FW de Klerk and the End of Apartheid in South Africa’ trailer

Speaking from New York, Rossier told the Daily Maverick that while many films had been made about Nelson Mandela and South Africa’s transition to democracy what had not been explored was what was behind De Klerk and the National Party’s decision to negotiate.

“For me, De Klerk is the consummate documentary subject: a complicated and misunderstood figure. He is often mentioned by historians as one of the most transformational leaders of our last century, alongside Mikhail Gorbachev. Yet he is often shrugged off by many as merely a pragmatist and opportunistic statesman who assured himself a soft landing. I believe the reality lies somewhere in between,” said Rossier.

Rossier’s film, co-produced with Cape Town filmmaker Naashon Zalk, opens with President Jacob Zuma’s announcement on national television on December 5, 2013 that “our beloved Nelson Rolihlahla Mandela, the founding president of our democratic nation, has departed”.

It moves immediately to the controversial memorial service held at FNB stadium and attended by 53 heads of state on Tuesday, 10 December. The camera focuses on ANC Deputy President Cyril Ramaphosa as he welcomes some of the country’s former leaders. At the mention of Thabo Mbeki’s name the crowd erupts in a deafening cheer and rises to its feet in the stands. As Ramaphosa welcomes De Klerk, the camera lingers on his face. De Klerk remains inscrutable, his expression fixed in a stony stare, his jaws rhythmically working a piece of gum while in the background the crowd delivers an equally rousing welcome at the mention of his name.

For those who survived Apartheid, in that moment, and unfairly perhaps, De Klerk’s appearance morphs into one image – that of the many balding, severe, tight-lipped, humourless conservative white, male Afrikaner leaders who preceded him and who were responsible for an ideology declared a “crime against humanity.”

That is the one burden – the burden of history – De Klerk still carries and it is one that has landed him in hot water, most recently in 2012 during an interview with CNN’s Christiane Amanpour.

De Klerk, responding Amanpour’s charge that he had never apologised for Apartheid or taken responsibility “for what your party did” replied that he had in fact apologised.

“I made a profound apology in front of the Truth Commission and on other occasions about the injustices…wrought by Apartheid. What I have not apologised for is the original concept of seeking to bring justice to all South Africans through the concept of nation states. But in South Africa it failed and by the end of the 70s we had to realise and accept and admit to ourselves that it had failed and that is when fundamental reform was started.”

These and other statements De Klerk made including that the former homelands had “a high degree of autonomy and self-governance”, and that the Apartheid government “poured [money] into those homelands to develop” (see Daily Maverick) unleashed howls of protest inside the country.

Later De Klerk explained that his remarks had been “widely misunderstood” and that these were in fact views that he had “long abandoned”. In other words, in simply retelling some of the history that led him and his party to 1990, Amanpour and viewers had mistaken them as an endorsement.

“I identify myself completely with the values and aspirations expressed in our Constitution and have dedicated myself, in my retirement, to doing everything I can to uphold the Constitution,” De Klerk wrote.

And it is through this maze of history and personality that Rossier navigates his film, allowing De Klerk to speak in his own voice “to let him make his point” followed by the opinions and thoughts of several other high-profile leaders or voices of the time including Thabo Mbeki, Albie Sachs, Mathews Phosa, Chester Crocker, Roelf Meyer, Leon Wessels, Yasmin Sooka and Richard Goldstone.

Most of these voices confirm the significant hurdles De Klerk faced and the courage it took to surmount them.

But do we get any closer to understanding De Klerk, the man, and what passions or convictions drove him?

Tony Leon, former leader of the DA, in his memoir Opposite Mandela (Jonathan Ball) writes “I have always wrestled in relation to my encounters with Mandela – and other leaders I met personally or viewed through the lens of history – with the difficulty of separating the power of human agency from what Karl Marx termed the ‘motive forces of history’, or the confluence of events and formations that propelled them. Undoubtedly while Mandela was at all times the servant and symbol of the political movement he came to lead, he also at key moments provided personal leadership that proved quite decisive in determining the course of this country.”

In many ways the quote can also be applied to De Klerk particularly in the sense that he provided personal leadership that proved decisive and that he was propelled by a confluence of events. Unfortunately in De Klerk’s case, the political party he served and came to lead carried within its DNA the seeds of its own destruction.

What Rossier’s film cannot ultimately penetrate is De Klerk’s heart, a heart that has grown the carapace of the consummate pragmatic politician. And that was the singular and unique magic of Nelson Mandela, he revealed his heart while at the same time keeping his head – the mark of a true statesman.

Whether De Klerk and the National Party he led were forced to the negotiation table because of a genuine change of mind with regard to the human cost of the ideology of Apartheid or because they had been forced there through internal and external resistance, the pressure of sanctions, the cutting off of bank loans and the collapse of the Soviet union, is never made quite clear. This is perhaps the only criticism of Rossier’s film – that these significant issues are touched on only briefly.

De Klerk, as a person, is not charismatic and does not provide much emotional traction for the viewer. He is, as Rossier says, a pragmatist, a man who himself says he “does not like to brag” when asked why his Nobel Prize is not on display on his bookshelf.

Rossier’s film does not try to recast De Klerk or “restore” him to some imaginary firmament of “iconic” South African leaders. The director does not shy away from asking De Klerk, and others, uncomfortable questions about the gross violations of human rights by successive white, minority governments.

Rossier probes De Klerk on his response to Vlakplaas death-squad killer, Eugene De Kock, who was sentenced to 212 years in prison for torturing, murdering and assassinating numerous activists and his assertion that his [De Klerk’s] hands were “soaked in blood”.

De Klerk once again categorically denies any knowledge of these hit squads or that they were part of the government’s official machinery. His response is contrasted by comments by Truth Commissioner Yasmin Sooka and Albie Sachs that it would have been impossible for him not to know.

Veteran editor and journalist Max du Preez also reminds Rossier that the newspaper Vrye Weekbald regularly wrote about death squads while De Klerk was president, so while he might not have personally had anything to do with these professional killers, he cannot claim not to have known of their existence.

And it is here that the burden of being on the wrong side of history weighs heavily on the stooped shoulders of the ageing De Klerk. We are left with a portrait of a guarded man who nonetheless has earned his place in history.

In the end, says Rossier, De Klerk was, for him, “an interesting figure because he was not under pressure to save his power and his own skin. De Klerk is the other side you need. We wanted to show this as otherwise what incentive do we give to others to surrender power this way in a negotiation? Many conflict and post-conflict countries will benefit from better understanding this flawed, yet ultimately successful political leader that managed to bridge two opposing worlds.”

Rossier and Zalk’s film is beautifully shot and edited and a dispassionate and balanced attempt at trying to understand a contentious yet significant player in the country’s contemporary history.

While South Africa moves on – and as some of the key players who helped to shape our democracy die – it is important that some trace of their contribution is captured and explored.

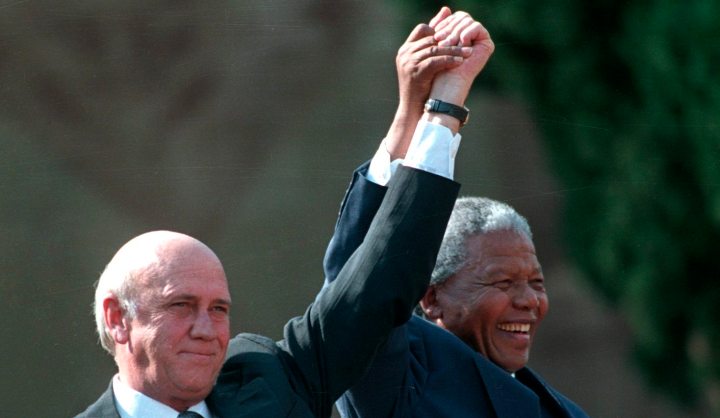

Earlier in the film Rossier asks a young woman in Soweto if she knows who the white guy is in a photograph. The photo is of Mandela and De Klerk with their hands held aloft after Mandela’s inauguration in 1994.

It takes her a while but eventually she smiles and says “ah yes, De Klerk”…but that is all she knows. DM

Photo: Nelson Mandela and former second Deputy President F.W. de Klerk after the first presidential inauguration on May 10, 1994. (REUTERS/Juda Ngwenya)

Become an Insider

Become an Insider