Maverick Life

Farewell Nadine Gordimer, creator of a universe of anger, angst, irony and hope

Nadine Gordimer’s extraordinary place in South African letters allows J. BROOKS SPECTOR to contemplate the complex interrelationship between the country’s politics and history and her astonishing literary career.

The voice on the telephone was in English but Scandinavian, slightly hesitant, ever so slightly apologetic and polite. The voice explained he was the deputy ambassador of the Swedish Embassy in Pretoria, and that he had a rather delicate matter to discuss with us in our capacity as an American diplomat. Uh oh.

The Swedish Academy had just informed him that they had decided to award Nadine Gordimer the Nobel Prize for Literature – but, before they announced it to the world, there was this small matter of speaking with her first, to make certain she would actually accept the prize. (There had been a couple of times when a recipient, like Boris Pasternak, had actually been forced to turn down a Nobel Prize, and they couldn’t have the embarrassment again.) The Academy had asked Swedish Embassy staff to speak with her first – just to make sure everything was okay.

The voice had tried to reach her at her home in Johannesburg, but she wasn’t in, and the person who had answered the phone had said that she was away – perhaps she was in America. Could this writer please help them out with this small problem?

There was the ever so slight tinge of the frantic in the voice on the phone. In response, the answer was, ah, yes, well, she was in America; she was staying with her son, Hugo, in New York City; but his surname wasn’t Gordimer, of course. Pre-Internet, we chased down some New York City phone books in our embassy. Fortunately there was only one H Cassirer listed in the Manhattan directory. Bingo. We gave them the phone number, wished them good luck in reaching her, and reminded them to at least wait until it was sunrise on the East Coast of the US before calling to wake up everyone in that household. Then, ever so politely, asked in return: When the Swedes gave a great reception in her honour over this prize, we would also crack their guest list for the event. And that is the way Nadine Gordimer learned she had received South Africa’s first Nobel Prize for Literature, back in 1991.

When she finally received that honour, Sture Allen of the Swedish Academy had said of her, “She makes visible the extremely complicated and utterly inhuman living conditions in the world of racial segregation. In this way, artistry and morality fuse.” In response, in her Nobel lecture, Gordimer could offer a political and literary credo in which she said, “This aesthetic venture of ours becomes subversive when the shameful secrets of our times are explored deeply, with the artist’s rebellious integrity to the state of being manifest in life around her or him. Then the writer’s themes and characters inevitably are formed by the pressures and distortions of that society as the life of the fisherman is determined by the power of the sea.”

This reporter was fortunate to have first become acquainted with her, years before that, back in the 1970s. Her international literary and political impact was already well in the ascendant but she could move easily throughout the city without difficulty. Her novels and short stories were already being critically acclaimed and embraced by international readers even as the South African government had banned a number of her novels.

Her collection of essays, The Black Interpreters, was an important milestone in critical responses to the impact and importance of a new generation of Black writers in South Africa. And her partnership with photographer David Goldblatt for their extended photo essay, On the Mines, was easily on a par with Walker Evans and James Agee’s Great Depression-era classic, Let Us Now Praise Famous Men.

At times, Gordimer could give the foolish or unwary a sense of being looked over, measured and found wanting, but she would quietly come to conferences and seminars that our office had frequently arranged during the 1970s as one way for her to understand the new voices arising in the country’s literary world. She had, by that time, of course, already been a major figure in Johannesburg’s non-racial literary and leftist political world, its “Bohemia”, for over two decades, at gatherings that included the likes of writers like Nat Nakasa, or rapidly rising political figures like Nelson Mandela, by the time her first novels and short stories were already being published at home and abroad. Years later, in the 1980s, she would be a founding member of the ANC-aligned Congress of South African Writers, or COSAW, an organisation that was rallying point for many of South Africa’s writers through its conferences, training efforts and its influential literary journal.

Many of her writings became guidebooks for me in understanding South Africa, back when I first arrived on these shores. Friends would quietly hand me a copy of A Guest of Honour, The Late Bourgeois World or A World of Strangers, wrapped in brown paper, and say to me, “Here, read this and understand us a bit better.” I found my own way to her short stories, to lapidary gems like Six Feet of the Country, a work that later became a fine short film as well. Her novel, The Conservationist, won the Booker Prize around that time as well – and its evocations of the conflicting values held by blacks and whites, Afrikaners and English speakers, made a vivid impression upon this writer, then and now.

In our second assignment in South Africa in the late 1980s, there had been an earlier telephone call, this one from Nadine Gordimer herself, rather than about her. She had been invited to lecture in America but her previous US visa had expired. Given the apparent hostility of the US government towards the ANC and other liberation movements, she had become concerned about the way her visa application would be received. (Apparently she had indicated somewhere on the form that, well, yes, she was affiliated with the ANC, and well…) This was a chance to introduce her to the consul general and to indicate to him that Gordimer’s place in the global literary world was such that a delay on her visa on such grounds would be terribly embarrassing for everyone. One could do things like that back then.

Throughout Nadine Gordimer’s long, productive life, her novels, fifteen of them, and dozens of stories poured forth from her typewriter – as well as some sustained literary criticism and more political essays – frequently on the questions of censorship and freedom of expression. For this writer, her literary works had created the tapestry of a fully realised, well-populated but fictional universe – not unlike the manner of writers like Charles Dickens and Honoré de Balzac.

She populated her fictional South Africa with a wonderful array of revolutionaries, liberals, radicals, racists and guerrilla fighters – as well as those with their heads deep in the sand. There were Africans, Indians, Coloureds and whites; Afrikaners and English; Jews and gentiles; big city folks and the denizens of small towns and farms; the old and the young. There were political naïfs as well as the politically committed, the crafty and political savvy. There were the cruel and the sensitive; the defiant, the downtrodden and the broken in spirit.

Of her own work, she had said, “Learning to write sent me falling, falling through the surface of the South African way of life.” And University of Massachusetts English professor Stephen Clingman, a scholar on her writing has said, “She knew that if you wanted to understand any character, black or white, you needed to understand the way politics entered into the very individual.” Clingman added, “She allowed us to see things about the political world that the political world could not really describe”.

Along the way, Gordimer sometimes noted it was some key events in her early years that had helped to first open her eyes to the depravity of apartheid society. These included such experiences as witnessing the dehumanising liquor raid of her black nanny’s small living quarters behind her parents’ home, during which her parents stood by silently. And there was her realisation that the black miners who patronised the shops run by men like her father were not allowed to touch the items in the stores before they bought them. Then there were her growing friendships with black writers she saw as talented as herself, but far less able to pursue their craft.

In a lecture she delivered at the University of Cape Town back in 1977, she had told her audience that her South Africa was “[n]ot one that most Europeans would recognise as Africa. But Africa it is. Although I find it harsh and ugly, and Africa and her landscapes have come to mean many other things to me, it signifies to me a primary impact of being; all else that I have seen and know is built upon it.” And in an interview in The Partisan Review published a few years later she explained, “I would like to say something about how I feel in general about what a novel, or any story, ought to be. It’s a quotation from Kafka. He said, ‘A book ought to be an ax to break up the frozen sea within us.’” Her works certainly were just such a tool.

For this writer, Gordimer’s stories always seemed to be, in that over-used phrase, “ripped right from the headlines.” “My Son’s Story” told of a conflicted young coloured man wavering between getting along carefully and entering into the liberation struggle. “Burger’s Daughter” was a thinly veiled portrayal of ANC hero Bram Fischer’s story, while “A Sport of Nature” followed the life of a white, politically radical woman who eventually became one of the wives of South Africa’s first black president. Later, in her novels “The House Gun”, “The Pickup” and “No Time Like the Present” Gordimer explored the uncertainties and unsettled times in South Africa’s post-Apartheid universe of rising urban crime, xenophobia and the sometimes uncomfortable sorting out of the nation’s new, more integrated, increasingly racially mixed society.

But July’s People, her short dystopian novel of a could-be near future, written back in 1981, in the wake of the country’s growing political turmoil in the years after the Soweto Uprising has always seemed to this writer to be an extraordinary warning – a shot across the bow of white South Africans – of what would happen if the repression never ceased. Like Karel Schoeman’s Promised Land, or JM Coetzee’s Life and Times of Michael K and Waiting for the Barbarians, July’s People was Gordimer’s stark warning for South Africans, in the long tradition of apocalyptic, “if this goes on,” novels.

In recent years, some critics could argue that Gordimer was one of those writers whose simultaneous blessing and curse it was to come to prominence under Apartheid. She would always be defined by that circumstance – whether she was celebrated for radical critique or condemned for her liberal “complicity”. Such critiques argued her post-Apartheid writing was a little out of touch – locked in the “grand narrative” line of the political saga, rather than engaging with the nuances of a democratic SA that actually defies easy generalisations. For yet others, there was criticism of what seemed to be her increasingly dour view of the outcome of South Africa’s non-racial transition.

But to this writer at least, rather than a lessened, worn-down spirit, her last novel, No Time Like the Present, with all its disjointedness, hesitations, switchbacks and ambivalences in the telling, actually seemed to capture precisely the unsettledness in the lives of the country’s young professionals. Those racially mixed couples, gay couples, and blended families, were – and are – trying to figure out if they would or should stay the course in a South Africa that seemingly no longer had a clear picture of its future anymore. It reads just like so many of the conversations one hears every day now.

Regardless of who was in charge of government, one thing never wavered in Gordimer’s public appearances and critical writing. This was her principled defence against government efforts, any government’s efforts, to censor writing or punish the writer for writing it. Her critical studies of other internationally prominent writers and major literary concerns appeared regularly in serious magazines around the world for decades. Indeed, to sum of her fictional and critical writing showed off a fierce work ethic. For decades she methodically locked herself in her study every day to produce the polished work that flowed forth from her typewriter.

She was not immune to controversy. Late in life, an agreement to allow Trinidadian writer Ronald Suresh Roberts to produce an authorised biography ended in acrimony. And in 2006 she was assaulted in a robbery in which she ended up being locked in a storeroom in her house, although she declined to move into a more protected residence as a result.

Gordimer had been raised in the mining town of Springs, on the East Rand, in a family of religiously non-observant, immigrant Jews. She attended the University of the Witwatersrand for a year, before dropping out to become her own best guide to a further education. Her first novel, The Lying Days, was published in 1953, but one of her short stories had already been accepted by The New Yorker magazine two years earlier. With these early accomplishments, her literary ascendency was already well on its the way while she was still young.

When a long time friend and guide to South African politics and literature, a man who had known her well from the 1960s onward, heard Gordimer had died, he wrote to me from the US to say, “A sad day for South Africa. Besides Nelson Mandela she is probably [one of] the best known, respected and beloved South Africans throughout the world. The first time I met her she touched me with her gentleness, sharp humor and sincerity. [She was] an author and intellectual for the ages. Her influence on all South African writers is immeasurable.” DM

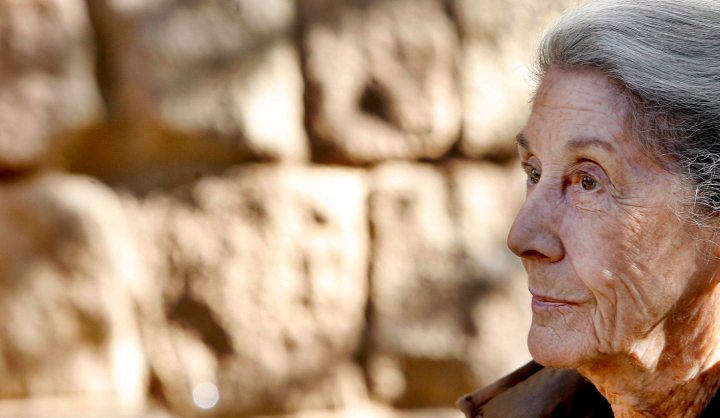

Photo: South African writer and Nobel Prize of Literature winner Nadine Gordiner poses prior to participating at events to commemorate the 85 anniversary of literary PEN CLUB of Catalonia, in Barcelona, Spain, 15 November 2007, which coincides with the International Day of Jailed Writer. EPA/ALBERTO ESTEVEZ

Read more:

- Gordimer and the secrecy Bill: Gag the mouth and block the ears in the Mail & Guardian

- Nadine Gordimer, The Art of Fiction No. 77 in the Partisan Review;

- Nadine Gordimer, Nobel laureate exposed toll of South Africa’s Apartheid in the Washington Post

- Nadine Gordimer, Novelist Who Took On Apartheid, Is Dead at 90 in the New York Times;

- South African Nobel Laureate Nadine Gordimer has died in her sleep at 90 in the Southafrican.com

- Nadine Gordimer dies aged 90 in the Guardian;

- Postscript Nelson Mandela in the New Yorker (one of Nadine Gordimer’s last pieces of sustained writing)

Become an Insider

Become an Insider