Maverick Life

Analysis: The Unbearable Whiteness of Being – Zelda La Grange’s journey & the continued unbundling of white identity

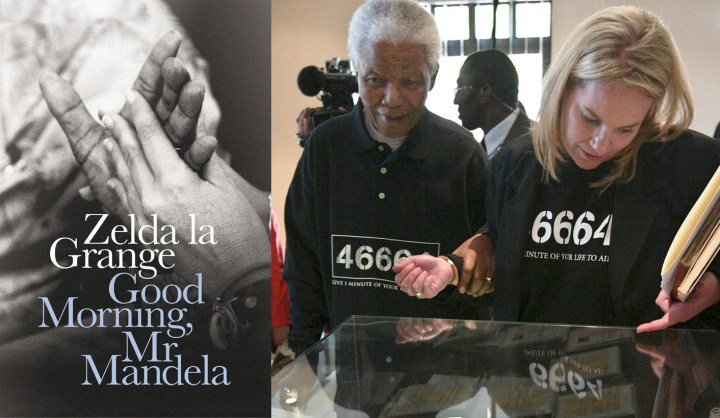

While Zelda la Grange’s memoir “Good Morning, Mr Mandela” is a searingly honest, moving and entertaining account of her years orbiting President Nelson Mandela, it is also an excavation of white (particularly Afrikaner) identity and one woman’s painful blossoming of a deeper consciousness. The book, says MARIANNE THAMM, will hopefully contribute to the ongoing debate about whiteness in contemporary South Africa.

In the past two weeks there have been several weighty pieces of writing about race, white identity, forgiveness, history and the process of unbecoming – well, for white South Africans at least.

At the weekend City Press published a piece by Professor Steven Friedman, Director of the Centre for the Study of Democracy, and which originally appeared on the SA Civil Society Information Service website in which he argued that it was the black middle class who are “our ticking time bomb” and not the poor. While poverty was our biggest problem, Friedman wrote, it is the black middle class who are “at the sharp end of the racial interface” and who continue to experience “the same racial attitudes and sense of exclusion [as a previous generation of black South Africans] even if the process is now subtler”.

“In the early 1990s, racial attitudes in the middle class were a major issue for a society negotiating a new political order. When democracy was achieved, the social power holders – business, the professions, academics, the media – seemed to decide that race was a problem no longer because everyone had the vote and formal rights. And so racial tensions that should have been addressed over the past two decades were ignored.”

While he would no doubt frame it in somewhat less subtle terms, it is an argument with which Julius Malema would probably wholeheartedly agree.

In a column below Friedman’s, Xolela Mangcu, associate professor of sociology at the University of Cape Town, praised the Prof’s voice as a courageous one as “many of those on the liberal left at the universities are attempting to banish ‘race’ instead of finding ways to talk about it.”

Zelda la Grange’s recently published memoir, Good Morning, Mr Mandela, (Penguin) while an engaging, at times funny and searingly honest account of her over 16-year association in one form or another – as typist in his office to secretary to personal assistant to the former president – offers an insider’s account of the personal transformation of an ordinary, white “boeremeisie” (as Mandela enjoyed affectionately stereotyping her).

Between the rich anecdotes of Madiba’s numerous encounters with the world’s powerful, wealthy and (in)famous – which she witnessed at close range – as well accounts of his personal quirks, virtues, foibles and torments, La Grange’s book sets out her own journey from naïve, completely unaware, conservative white South African to more conscious human being.

This might seem like a mere incidental contribution to the mainstream media discussion about race and privilege in South Africa, but La Grange’s self-effacing and honest account – from her initial crippling fear of encountering Mandela, a man her family had viewed as a terrorist, to her growing deep understanding of the man, his life and the history that shaped him (as well as the lives of the majority of South Africans) is an important contribution to the ongoing discussion.

Many who might shy away from or who become defensive at the often (necessary) abrasive tone of the public debate on race, might find easier traction and understanding in La Grange’s tender story.

Nelson Mandela and Zelda la Grange were two individuals, chess pieces on a bigger board game of history, the currents shaping each of their lives, causing collateral damage, of course of degrees so varied they cannot in any way be compared. But there they were in time, in space, in each other’s orbit.

Of course it is through and because of Nelson Mandela that La Grange begins to grasp the metanarrative he embodied for the world; that of “spiritual enlightenment” of forgiveness, of self-actualisation and a deeper understanding and awareness of the shared bonds of humanity and the pain we inflict on others, some of us while fully aware, others by not asking questions and some simply through ignorance and willful blindness.

This was the Mandela who joined the ranks of other exceptional global icons including Gandhi, the Dalai Lama, Mother Theresa or their more popular “lite” equivalents, Oprah or Deepak Chopra.

But while La Grange comes to recognise these universal human qualities Mandela personified, she also came to understand the consequences of structural inequality, of colonialism, of Apartheid, the dispossession of the majority – and in so doing, was forced to turn inwards and examine herself.

And it is in owning her shame – shame at her ignorance, shame at her lack of knowledge, shame at her political beliefs, the shame of history – that La Grange finds her humanity restored and herself liberated and released.

There is, of course, the argument that once again a white person has “found themselves” through the kindness, generosity and patience of a man who represented the majority of the oppressed. Some do ask when the time will come when the perpetrator class and its descendants will embark on this journey out of our own volition, unprompted by the victims and survivors of the system.

Earlier this month, on 18 June, the New Republic published an extraordinary piece by author Eve Fairbanks about Adrian Vlok, minister of law and order between 1986 and 1991, who appears to have done just that, i.e. continued the journey of his own volition (or rather, prompted by his faith).

Vlok, Fairbanks reminds us, was the Apartheid government’s most notorious police minister. It was on his watch that thousands of anti-Apartheid activists were murdered through “cloak and dagger” tactics including assassinations and poisonings. One victim was the Reverend Frank Chikane, who survived an attempt when his underwear was infused with poison. In 2006 Vlok arrived at the Union Buildings and offered to wash Chikane’s feet.

Fairbanks writes: “Vlok, however, began to quake. As he realised what he was about to do, all the loathing and feelings of superiority inculcated in him since boyhood suddenly rose to the surface. ‘I’d grown up thinking it should be the other way around: that blacks should be serving whites,’ he thought to himself. Waves of physical disgust at the thought of touching Chikane’s toes surged through him.”

Vlok had anticipated this response and had prepared himself by writing in his Bible; “I HAVE SINNED AGAINST THE LORD AND AGAINST YOU! WILL YOU FORGIVE ME?”

“Silently, he handed the Bible to Chikane, pulled a rag and bowl out of his briefcase, slid off the chair onto his knees, and bowed his head. Finally, stutteringly, he asked Chikane, ‘Frank, please, would you allow me to wash your feet?’” Fairbanks writes.

Later she observes that Vlok’s repentance “is unsettling for whites on an even deeper level because many do wonder, deep down, if the whole white way of life in South Africa might be somehow immoral. In the mid-2000s, a punk Afrikaans band released a music video that interspliced grainy, home-video-style bucolic footage of white toddlers playing on bicycles with soldiers goose-stepping: the recognition that every ordinary pleasure of white South African life is associated with a price tag of repression and violence. The Afrikaner poet Danie Marais, who grew up under Apartheid, has written of the shame he feels when he thinks even about his first kiss: ‘It seems unlikely, almost perverse, that one’s own personal experiences of beauty and innocence could have happened in such a time and place’.”

One cannot argue that the nature of this type of self-reflection for white South Africans, while it might not be one captured in mainstream media, marks a necessary deepening of the debate and the discussion – of discovering how to “unbecome” in order to become, in order to live in one’s skin. How to find, as La Grange has done, a space where one can live with oneself, own your history and understand your role in the future.

TO Molefe, essayist, columnist and author, who is working on a book on attitudes toward and perceptions of race and reconciliation in post-Apartheid South Africa, remarked to Fairbanks of Vlok’s ongoing acts of contrition in the townships in and around Pretoria, “It’s not entirely of symbolic coincidence that, when he washed his victims’ feet, he washed his own hands, too.”

That may well be the case, but at least Vlok has embarked on the uncomfortable work of self-reflection and reparation.

In a piece for the website Africa Is A Country, Molefe, wrestling the narrative and the focus away from its ongoing focus on the need for white transformation, had this to say to young black South Africans who had attended a debate hosted by the Institute for Justice and Reconciliation on “intergenerational” justice and who had found themselves bereft of language to understand the country they live in: “History cannot be sealed off from the present through watershed moments, no matter how appealing their emotive value. History is not something that can simply be ‘moved on’ from, not without a radical and massive correction of historical injustices; something that did not happen in this country. Even with such a correction, history is always the lens through which to understand the present.”

In many ways La Grange’s book will offer readers, hopefully many of them young white South Africans, an unusual opportunity for engaging with “their” history and perhaps also finding a language with which to understand the world in which they find themselves today and why race still matters and why discussions about the issue are not to be feared but welcomed.

La Grange’s book will be read far and wide, hopefully not only because readers are looking for sensational peccadilloes about the Mandela family – but because the discussion and debate needs to continue, widen and deepen.

If we don’t find new ways of engaging, we will be doomed to listen to the rhetoric yelled from the extreme, angry edges of the debate.

“I am product of that change,” Le Grange writes of her journey with Nelson Mandela and that, apart from the incredible story she tells, is one of its enduring lessons we can take into the future. DM

Photo: A file image dated 21 September 2004 shows late former South African president and Nobel Peace prize holder, Nelson Mandela (L) and his personal assistant Zelda le Grange (R) looking at some of his personal diaries in Johannesburg, South Africa. EPA/KIM LUDBROOK

Become an Insider

Become an Insider