Maverick Life

Fifty years later, time for Nat Nakasa to return home

The announcement that South African government offices are trying to repatriate the remains of exiled journalist Nat Nakasa encourages J. BROOKS SPECTOR to contemplate exile and the rainbow nation in Nakasa’s life and writing.

A few years ago, a sometime co-author, an economist working in Washington, and this writer got to talking about exiles and their place in South African culture, one night over dinner. It turned out this hard-nosed resource economist, following a hard day of number crunching, liked to listen to jazz recordings by bassist Johnny Dyani, one of the key members of the Blue Notes, a group led by pianist Chris MacGregor. The Blue Notes had been South Africa’s first truly integrated professional jazz band. But, as a result of the pressures of Apartheid restrictions on their performances and work together, MacGregor, Dyani and the rest of the group eventually left South Africa in 1964. Dyani finally settled in Scandinavia where he lived and worked until his death.

And then, of course, there was Dumile Feni, the artist whose fans and critics came to call “the Goya of the townships” because of the emotional intensity about his subjects evident in so much of his work. Feni, too, left South Africa for America in 1968, seeking artistic freedom. While both men died in exile – Dyani in 1986 and Feni in 1991 – their remains were eventually repatriated for reburial on home soil.

It is of course true that many other artists went abroad in the dark years. Names like Hugh Masekela, Abdullah Ibrahim, Wally Serote, and Miriam Makeba come easily to mind as individuals whose reputations grew steadily while they lived outside of the country. Fortunately for him, Masekela found a niche, a home away from home, as a young man in New York City’s cool jazz scene. And Miriam Makeba, originally under the tutelage of Harry Belafonte, became an international fixture of a growing folk movement in the American music scene – and then around the world – even as she also became a vigorous campaigner against South Africa’s Apartheid regime.

For these artists too, of course, the pull of home seemed to remain irresistible – even though it took many years before they could finally return to pick up the threads of creative lives in South Africa. While such artists all faced creative and personal struggles, many eventually found the artistic freedom they had sought and – sometimes – personal reward and great artistic success followed as well while they were abroad. However, others fell through the cracks in the way Dumile Feni seemed to do by the end of his life.

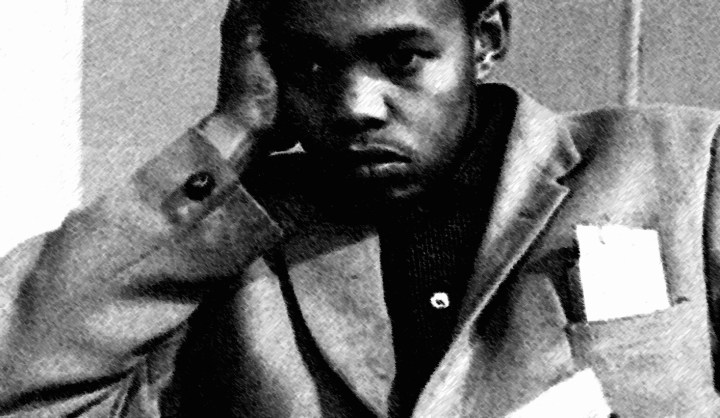

But one name, Nathaniel Ndazana Nakasa, stands out from the Apartheid era. Still only in his twenties, Nat Nakasa had already become a stalwart of Drum magazine in the company of writers like Henry Nxumalo, Lewis Nkosi, Casey Motsisi and Can Themba. Amazingly, too, for a time when it must have been a virtually unthinkable circumstance, Nakasa soon became a regular columnist with a byline in the Rand Daily Mail, years before the paper became a uncompromising critic of the then-political order. And in all of this he also found the time to establish an influential journal of opinion, “The Classic”.

As biographer Heather Acott described him, “Perhaps uniquely for a black journalist – or for any South African journalist of the time – Nakasa found he was able to move easily among the many social, economic, intellectual, racial and ethnic streams in Johannesburg. Apartheid denied Nakasa access to white suburbs, a denial he observed largely in the breach. From the start, his reaction was that ‘the best way to live with the colour bar…was to ignore it.’ [Nadine] Gordimer describes this as Nakasa’s ‘period of no fixed abode… homeless and yet curiously more at home in Johannesburg than those behind their suburban front doors… Nat belonged not between two worlds but to both of them’.”

Acott added, “In an often quoted column entitled ‘Johannesburg, Johannesburg’, he describes his arrival thus: ‘I had travelled from Durban, over four hundred miles by train, to start working as a journalist. After work I often slept on a desk at the office or stayed overnight when friends invited me to dinner in their homes. This was not because of a Bohemian bent in me. Far from it. According to the law, ‘native’ bachelors are supposed to live in hostels in Johannesburg. I should have shared a dormitory with ten or more strange men… Instead of this, I chose to be a wanderer. I didn’t really want a hostel bed’ … Thus, for roughly eighteen months, on and off, I wandered about without a fixed home address. I determined to make the best of it.’ ”

Of his arrival at the Drum office, already-established writer Can Themba would write about Nakasa in his essay, “The Boy with the Tennis Racket”, “He had a puckish, boyish face, and a name something like Nathaniel Nakasa. We soon made him Nat… He came, I remember, in the morning with a suitcase and a tennis racket – ye gods, a tennis racket! We stared at him. The chaps on Drum at that time had fancied themselves to be poised on a dramatic, implacable kind of life. Journalism was still new to most of us and we saw it in the light of the heroics of Henry Nxumalo, decidedly not in the light of tennis, which we classed with draughts.”

Then, while still a young man and barely settled into his journalism career, in 1963, Nakasa learned he had been awarded one of those ultra-prestigious Nieman Fellowships – the scholarship given to a very select group of American and world journalists each year to attend whatever courses they wanted to at Harvard University for an academic year – with all expenses paid. [Daily Maverick’s Greg Marinovich is the 2013/14 Nieman Fellow from South Africa – Ed]

But the South African government declined to issue Nakasa a passport to travel abroad – passports often being a very tough thing to prize out of the South African government back then.

(As a personal footnote, when the author worked for the American Embassy back in the early 1970s, there was often a battle of wills with the South African Interior Ministry to extract a passport for people who had been invited to visit America for various study tours at US government expense. These tussles sometimes lasted down to the actual day of the would-be visitor’s airport departure.)

Without a valid passport, Nakasa couldn’t apply for a US visa (or any other visa, for that matter), let alone depart for Harvard and his Nieman Fellowship. The weeks ticked by and an increasingly desperate Nakasa finally was given an exit permit. This document allowed him to leave the country – but by accepting it he had forfeited the right to return. Ever. Nevertheless, as the time to depart came close, Nakasa wrote of his upcoming departure, “Sometime next week, with my exit permit in my bag, I shall cross the borders of the Republic and immediately part company with my South African citizenship. I shall be doing what some of my friends have called, ‘taking a grave step’.”

In Tanzania, he finally obtained an international travel documentation that allowed him to travel to the US, months after his Nieman year was supposed to have begun. Said Nobel laureate Nadine Gordimer of this emotional rollercoaster of a period for Nakasa:

“It was a strange time, the last year in South Africa; on the one hand, he was making a name for himself in a small but special way that no African had done before, his opinions and ideas were being considered seriously by white newspaper-readers whose dialogue across the colour line had never exceeded the command, do-this-or-that, and the response, yes-baas. On the other hand, he had been awarded a scholarship to Harvard and was involved in the process of trying to get a passport – for an African, a year-long game in which the sporting element seems to be that the applicant is never told what you have to do to win, or what it was he did that made him lose.”

But things seem to have gone wrong for Nakasa after he arrived in America. Ever the “man about town”, sliding between the racial lines of the parallel, segregated universes of South Africa in the ’60s, Nakasa seemed increasingly unable to settle into his new environment. On 14 July 1965, he jumped to his death from the window of a seventh floor apartment in Manhattan. He was buried in Ferncliff Cemetery in New York City, close to where Malcolm X had been buried five months earlier.

Of Nakasa’s increasing emotional turmoil, Nakasa biographer Ryan Brown had written, “Now he was caught in a precarious limbo, unable to return to South Africa but lacking citizenship in the United States, a place that he was beginning to feel offered little respite from the brutal racism of his own country. He was, he had written, a ‘native of nowhere… a stateless man [and] a permanent wanderer’, and he was running out of hope. Standing in that New York City apartment building, he faced the alien city. The next thing anyone knew, he was lying on the pavement below. He was 28 years old.” And Nadine Gordimer had gone on to say, “The truth is that he was a new kind of man in South Africa he accepted without question and with easy dignity and natural pride his Africanness, and he took equally for granted that his identity as a man among men, a human among fellow humans, could not be legislated out of existence, even by all the Apartheid laws in the statute book, or all the racial prejudice in this country. He did not calculate the population as sixteen millions or four millions, but as twenty. He belonged not between two worlds, but to both. And in him one could see the hope of one world. He has left that hope behind; there will be others to take it up.”

Despite that untimely and early death, Nakasa still left a wide-ranging body of essays and reportage that have come to be regarded as a unique vantage point, looking at a Johannesburg that was ostensibly two entirely separate universes – but also with a small, “below the radar” cosmopolitan world – the space described by writers like Nadine Gordimer in her novel, A World of Strangers. Nakasa’s wanderings allowed him to sample the demi-monde of the city’s largely black world that without Nakasa’s writing remained mostly unknown to his ordinary white readers. Some of Nakasa’s most enduring pieces are his acutely observed cameo profiles of figures like the legendary boxer King Kong, the famous penny whistler Spokes Mashiane, and a young, vivacious Winnie Mandela – as well as Aunt Sallie in her eponymous shebeen.

Nakasa even seemed to be oblivious of the need to have his internal passbook, his dompas, at the ready, or to adhere to those “white by night” evening curfews that were still in force. In contrast to the usual malign descriptions of these restrictions in the works of most black writers of the period or even later, Nakasa could write, “Fortunately, like most young men from the smaller towns in South Africa, I was thrilled by simply being in Johannesburg. While others made for their homes hurriedly at the end of the day, I took long leisurely walks from one end of the city to another.”

And anticipation of Archbishop Tutu’s invocation of the rainbow nation, poet and novelist Mongane Wally Serote could say about Nakasa, “To quote Tutu … Nat Nakasa was a rainbow man. Before the rainbow was allowed.” Or, as Nakasa had written, “Some people call it ‘crossing the colour line’. You may call it jumping the line or wiping it clean off. Whatever you please. Those who live on the fringe have no special labels. They see it simply as LIVING.” And Serote added, “I must tread softly. This is time-bomb ground – the world of Nathaniel Nakasa. The man who, with a subtle humour in the mind, and a sharp bitterness in the heart, set out and attempted to create order out of the disorder of the South African white prejudice and racism and that other thing, South African black timidity and subservience.”

Now, nearly fifty years after Nakasa plunged to his death, the national Department of Arts and Culture and the KwaZulu Natal and eThekwini governments, in association a group of South African writers and journalists, are planning to repatriate Nakasa’s remains for reburial back in his native land. The petition to do this has been filed in the New York State Supreme Court and the various parties are now hopeful arrangements can be made so that he can be reburied in the cemetery in Chesterville, KwaZulu Natal, the area where he grew up, although he was born in Lusikisiki in the Eastern Cape.

Beyond Nakasa’s reputation from his work, a national journalism award bearing his name is now given annually to individuals “working in the broadcast, online or print media who show exceptional integrity and courage in their work.” Presented by Print Media SA, the SA National Editors’ Forum and the Nieman Society, it is a recognition of Nakasa’s unique place in the nation’s journalism tradition. DM

Read more:

- “Nat Nakasa: an African Flaneur” by Heather Acott in Internet-Zeitschrift für Kulturwissenschaften. No. 18/2011

- “About Nat Nakasa” at the Sanef website;

- Nadine Gordimer’s essay, “One Man Living Through It” in “The World of Nat Nakasa”, available electronically from the U. of KZN;

- Dumile Feni in South African History Online;

- He’s Home Again – Memories Of S. African Bassist Johnny Dyani.

Become an Insider

Become an Insider